The Sacred Valley of the Incas or the Urubamba Valley is a valley in the Andes of Peru, 20 kilometres (12 mi) at its closest north of the Inca capital of Cusco.

The valley, runs generally west to east, is understood to include everything along the Urubamba River between the town and Inca ruins at Pisaq westward to Machu Piccu, 100 kilometres (62 mi) distant. The Sacred Valley floor has elevations above sea level along the river ranging from 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) at Pisac to 2,050 metres (6,730 ft) at the Urubamba River below the citadel of Macchu Piccu.

So most tourists start their trip to Peru in the valley or even straight to Macchu Pichu which is relatively low in terms of altitude sickness.

Though as a Cuzcena pointed out, setting the Cuzco airport at right angles to the valley means every international tourist is obliged to fly into Lima and catch a second smaller plane to Cuzco, where most of them want to be. It was said with a degree of bitterness that’s hard to dispute. Given a choice, we wouldn’t have bothered with Lima, and it’s difficult to imagine any other tourist having a different view.

On both sides of the river, the mountains rise much higher, especially to the south where two prominent mountains overlook the valley: Sahuasiray, 5,818 metres (19,088 ft) and Veronica , 5,680 metres (18,640 ft) in elevation.

The glaciers of these mountains provide water for crops and for the supply of towns throughout the Valley, though as the world heats up, the glaciers seem to be on the retreat. The intensely cultivated valley floor is about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) wide on average. Side valleys and agricultural terraces expand the cultivatable area, though many of the terraces are unused, either because they’re protected as part of a historic site, or because after the Spaniards the irrigation system broke down and can’t be reconstructed.

The Sacred Valley was the most important area for maize production in the heartland of the Inca Empire and access through the valley to tropical areas facilitated the import of products such as coca leaf and chile peppers to Cuzco.

The climate breaks into two seasons, wet (October – April) and dry and monthly average temperatures range between 15.4 °C (59.7 °F) in November, the warmest month, to 12.2 °C (54.0 °F) in July, the coldest month. At this time of year, the sun rises at around 6am and sets around 6.30pm though it’s position at the equator means there’s probably only half an hour difference whatever the time of year. The difference in temperature between night and day is much more extreme. Waking early before sunrise and the temperatures outside were below zero. As soon as the sun came out (which was very quickly) the temperature rose to around 20C. So having been warned to take Winter clothes, we actually enjoyed a British Summer time (yes, it really is mostly 20-25C at the height of Summer here).

Our first trip from our hotel in the Valley was to the site at Ollantaytambo, mainly because as the furthest day trip from Cuzco, numbers are a lot lower in the morning.

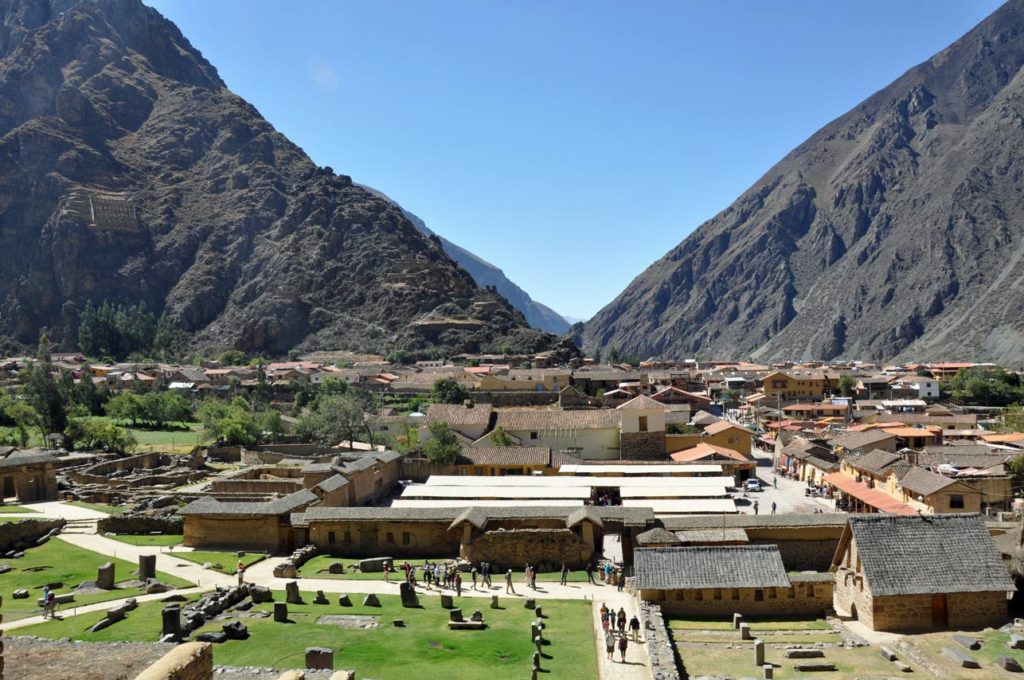

Ollantaytambo is a town and an Inca archaeological site in southern Peru partway down the Sacred Valley, northwest of the city of Cusco.

Most importantly as a visitor from sea level, it is at an altitude of around 2,792 metres (9,160 ft) above sea level. During the Inca Empire, Ollantaytambo was the royal estate of Emperor Pacahuti who conquered the region, and comes up a lot in conversation with guides travelling the country. He built the town and a ceremonial center.

At the time of the Spanish Conquest, it served as a stronghold for Manco Inca Yupanqui, leader of the Inca resistance.

Nowadays, it is an important tourist attraction on account of its Inca ruins and its location en route to one of the most common starting points for the four-day, three-night hike known as the Inca Trail. It’s where you’ll catch the train to Machu Pichu, if starting in the Valley.

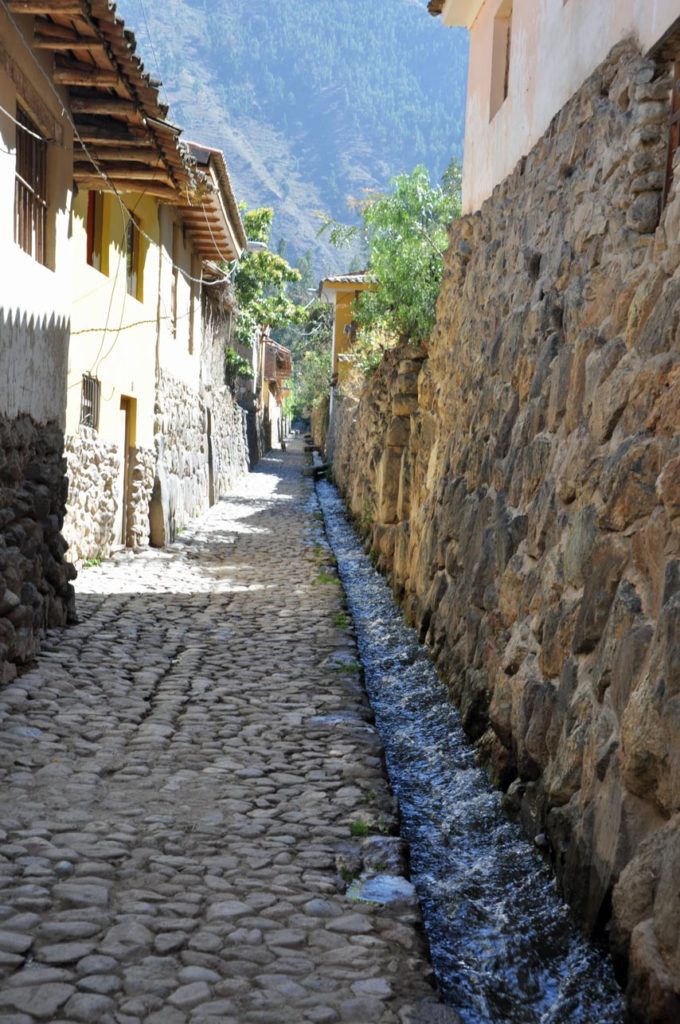

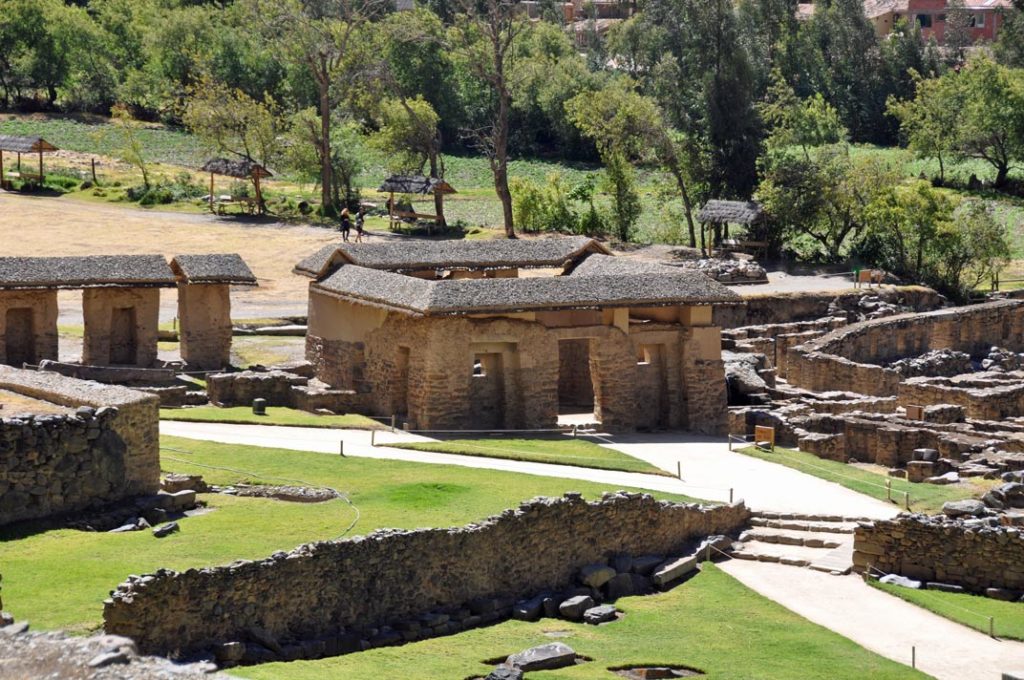

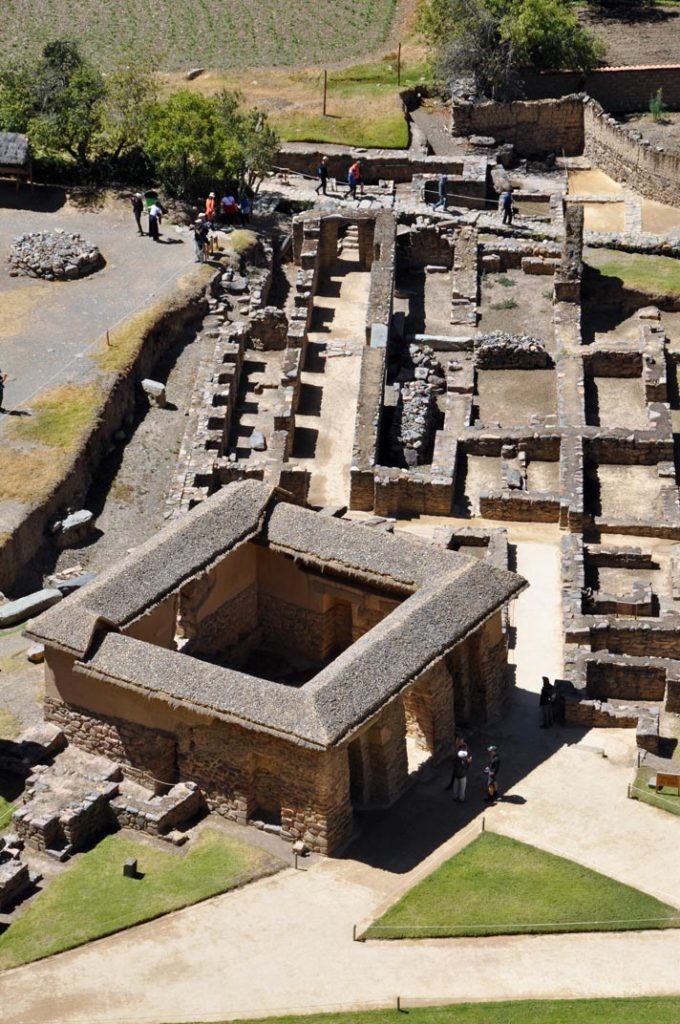

The main settlement at Ollantaytambo has an orthogonal layout with four longitudinal streets crossed by seven parallel streets. At the center of this grid, the Incas built a large plaza that may have been up to four blocks large; it was open to the east and surrounded by halls and other town blocks on its other three sides. All blocks on the southern half of the town were built to the same design; each comprised two kancha, walled compounds with four one-room buildings around a central courtyard.

Ollantaytambo dates from the late 15th century and has some of the oldest continuously occupied dwellings in South America. Its layout and buildings have been altered to different degrees by later constructions, for instance, on the southern edge of the town an Inca esplanade with the original entrance to the town was rebuilt as a Plaza de Armas surrounded by colonial and republican buildings. The plaza at the center of the town also disappeared as several buildings were built over it in colonial times.

‘Araqhama is a western part of the main settlement, across the Patakancha River; it features a large plaza, called Manyaraki, surrounded by constructions made out of adobe and semi-cut stones.

And as a tourist town there are people willing to open up their courtyards and allow you total a look inside the walls. Each “house” consists of a single room with a mezzanine. Cooking is over an open fire with a hole in the roof to allow the smoke to escape.

And the minute someone rattles a bunch of barley grass the ever-present guinea pigs rush towards the food. They’re obviously hugely picturesque, even when the guide points at the largest and fattest as next week’s likely lunch.

Towns along the main road have endless restaurants with ladies standing at the side waving rotisserie guinea pigs looking very like roast rats, in an attempt to lure people in for lunch – not tempted. But the house also includes a lot of totems or charms which are a bit gruesome and sit somewhat uneasily with the catholicism we were expecting, including lama foetuses (apparently very expensive), skulls from dead relatives etc.

These buildings have a much larger area than their counterparts in the main settlement, they also have very tall walls and oversized doors. To the south there are other structures, but smaller and built out of fieldstones. ‘Araqhama has been continuously occupied since Inca times, as evidenced by the Roman Catholic church on the eastern side of the plaza.

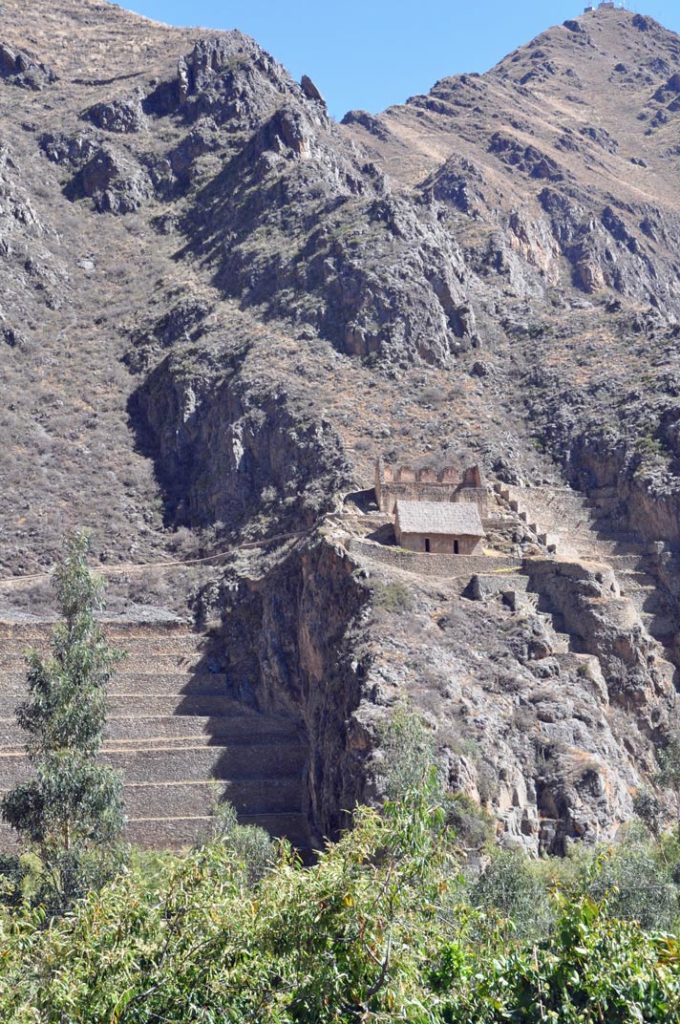

And up on the hills above there are food stores where maize and dried potatoes would be put away in the good years for the expected years of fallow during el nino etc. The potatoes at least look like the most unappetising, stones but in times of hunger they would fill you up and keep a family going. The Incas storehouses or qullqas were built out of out of fieldstones on the hills surrounding Ollantaytambo. Their location at high altitudes, where there is more wind and lower temperatures, defended their contents against decay. To enhance this effect, the Ollantaytambo qullqas feature ventilation systems. It is believed that they were used to store the production of the agricultural terraces built around the site. Grain would be poured in the windows on the uphill side of each building, then emptied out through the downhill side window.

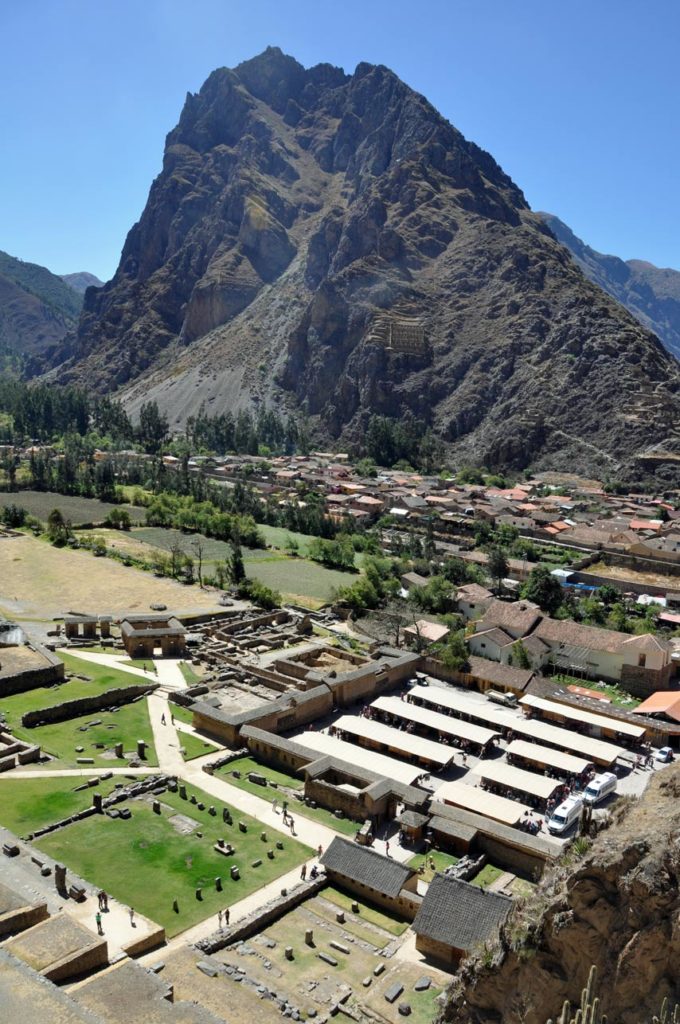

To the north of Manyaraki there are several sanctuaries with carved stones, sculpted rock faces, and elaborate waterworks, they include the Templo de Agua and the Baño de la Ñusta. ‘Araqhama is bordered to the west by Cerro Bandolista, a steep hill on which the Incas built a ceremonial center. The part of the hill facing the town is occupied by the terraces of Pumatallis, framed on both flanks by rock outcrops.

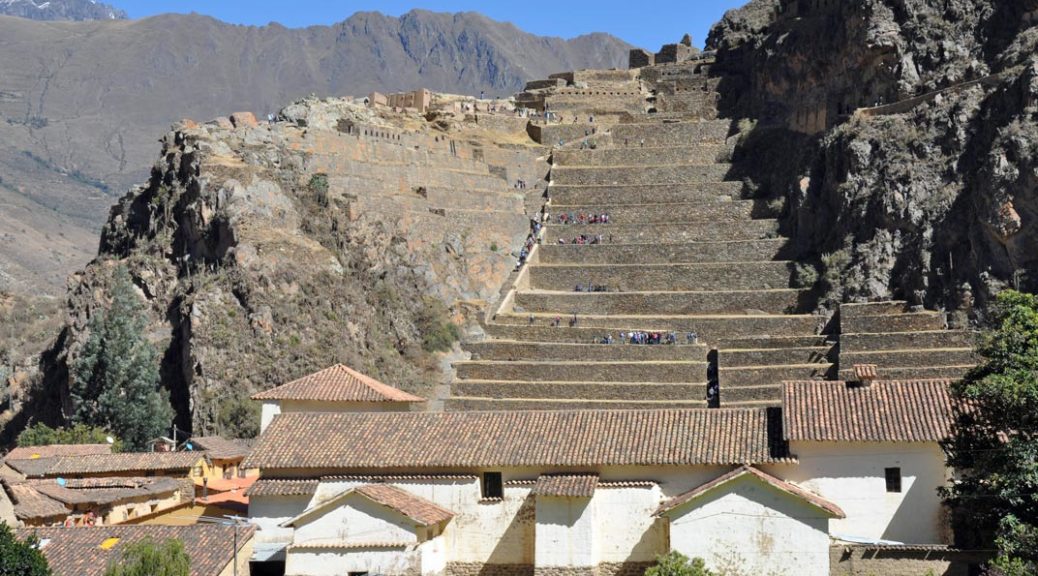

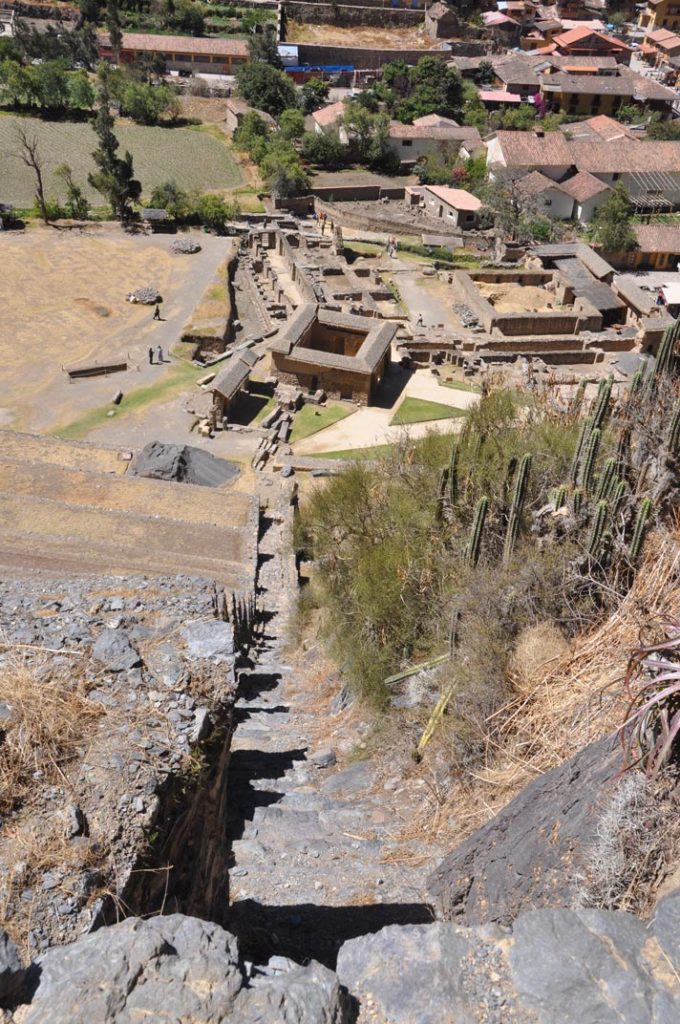

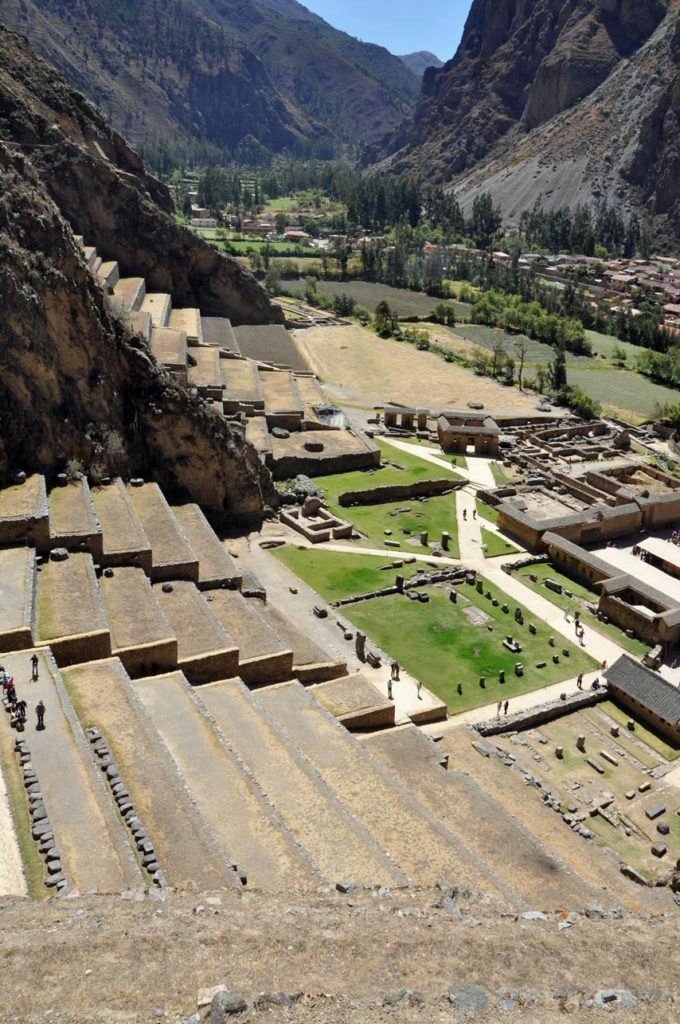

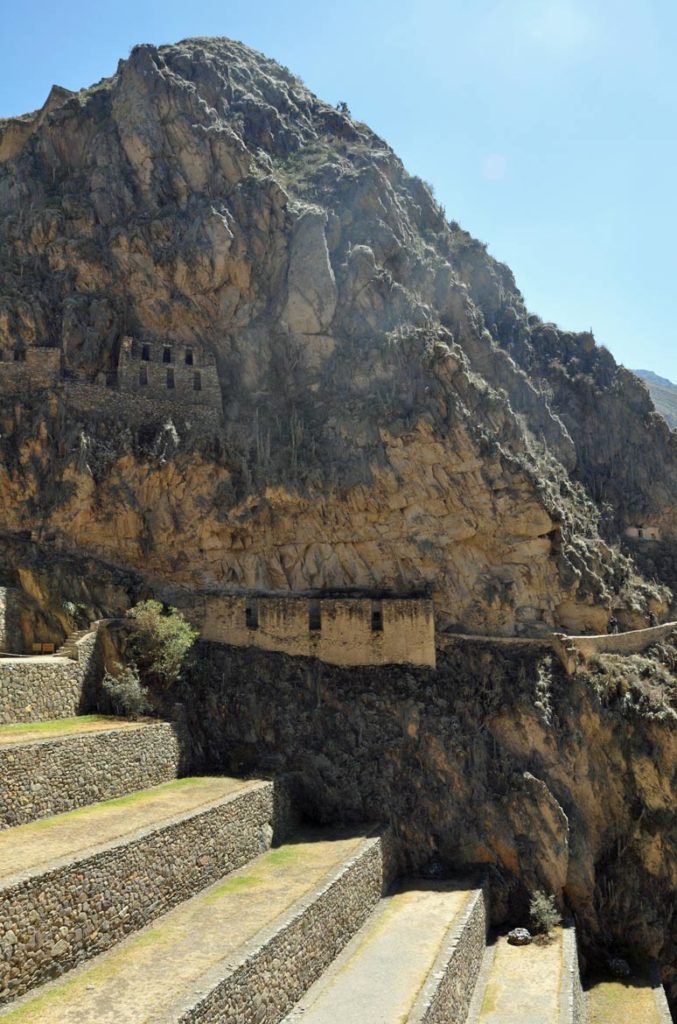

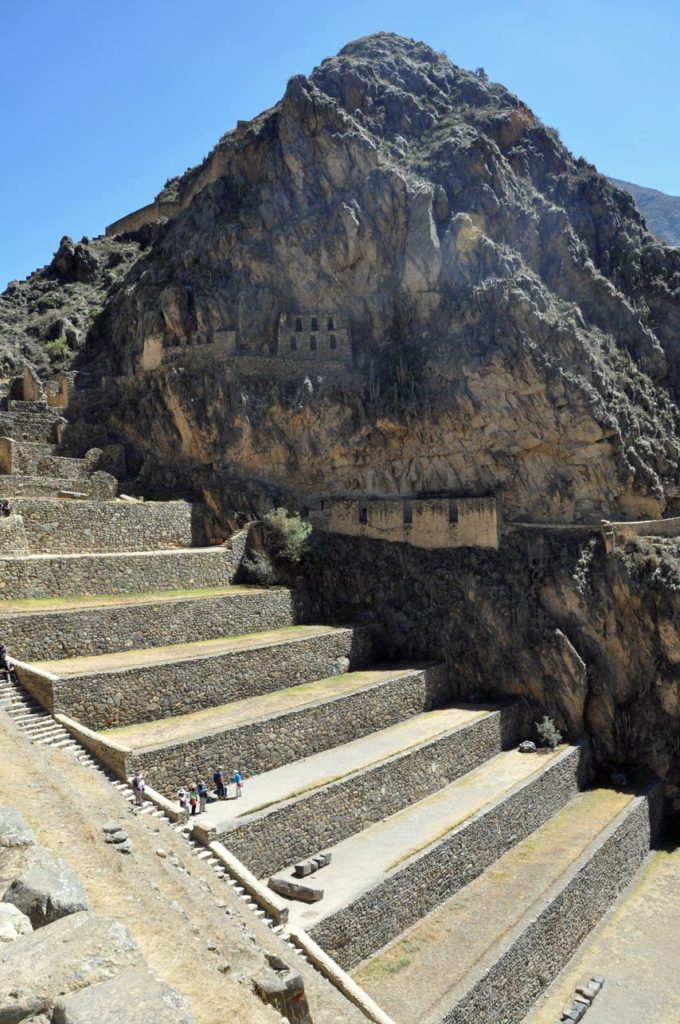

Due to impressive character of these terraces, the Temple Hill is commonly known as the Fortress, but the main functions of this site were always religious. The main access to the ceremonial center is a series of stairways that climb to the top of the terrace complex. At this point, the site is divided into three main areas: the Middle sector, directly in front of the terraces; the Temple sector, to the south; and the Funerary sector, to the north.

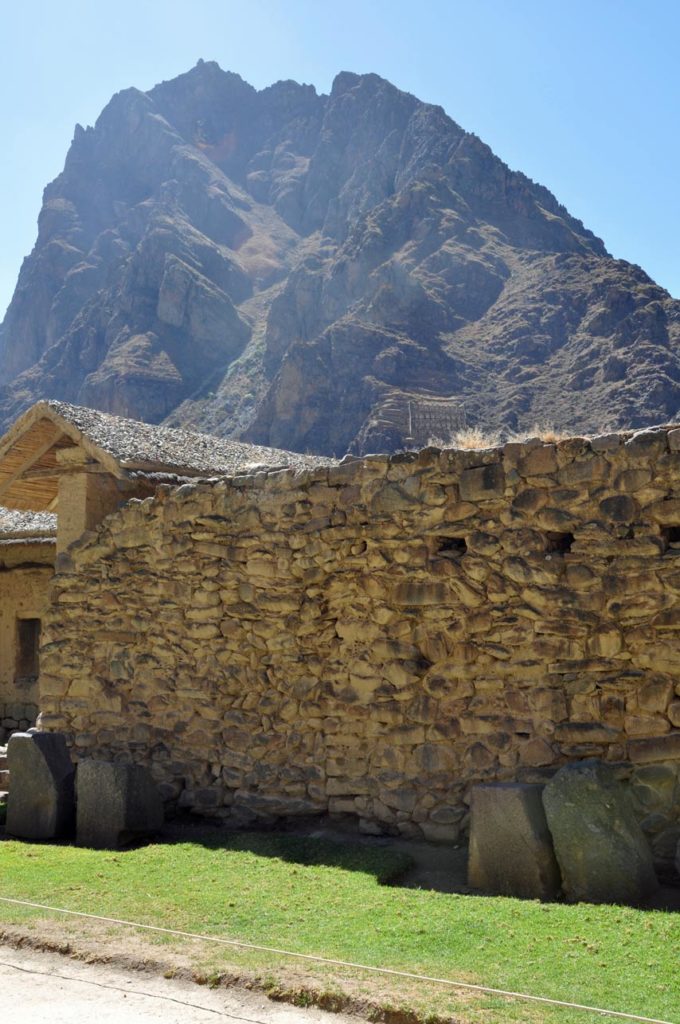

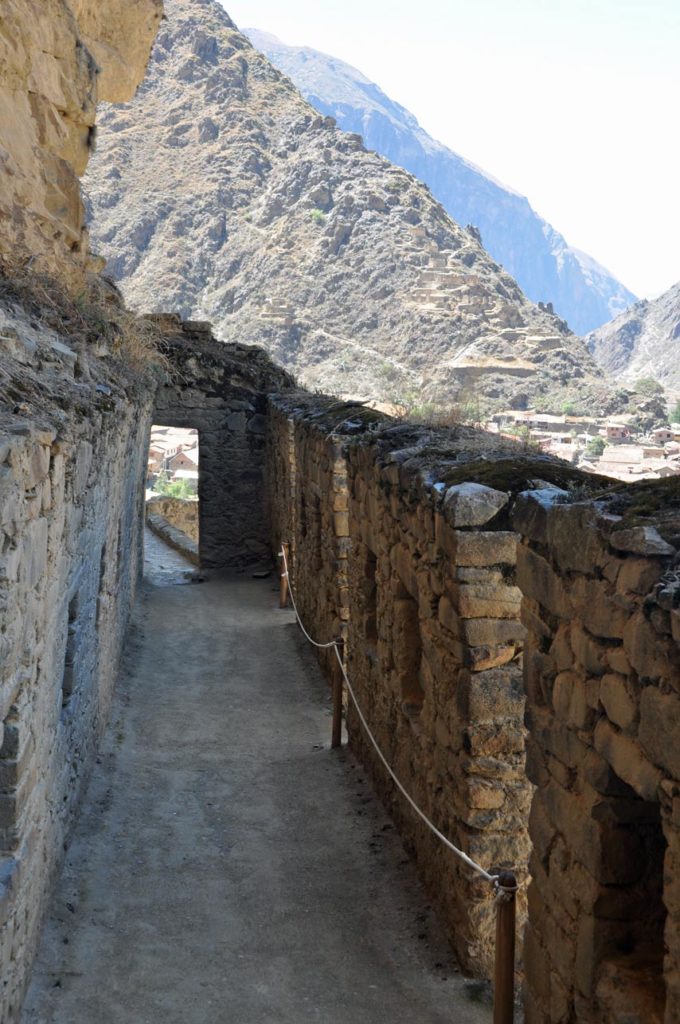

And it’s an excellent introduction to the incredible engineering and stonework of the Inca sites, with dry stone walls full of precision cut blocks and trapezoidal doorways (no arches). The Temple sector is built out of cut and fitted stones in contrast to the other two sectors of the Temple Hill which are made out of fieldstone. It is accessed via a stairway that ends on a terrace with a half finished gate and the Enclosure of the Ten Niches, a one-room building.

Behind them there is an open space which hosts the Platform of the Carved Seat and two unfinished monumental walls. The main structure of the whole sector is the Sun Temple, an uncompleted building which features the Wall of the Six Monoliths. The Middle and Funerary sectors have several rectangular buildings, some of them with two floors; there are also several fountains in the Middle sector.

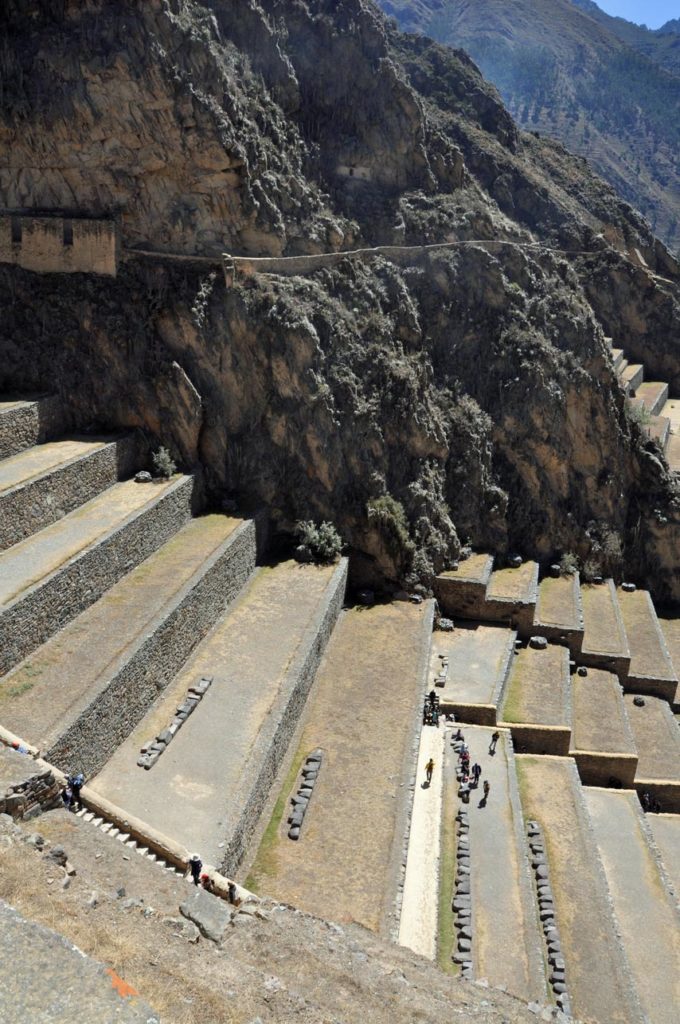

The valleys of the Urubamba and Patakancha rivers along Ollantaytambo are covered by an extensive set of agricultural terraces or andenes which start at the bottom of the valleys and climb up the surrounding hills. The andenes permitted farming on otherwise unusable terrain; they also allowed the Incas to take advantage of the different ecological zones created by variations in altitude. Terraces at Ollantaytambo were built to a higher standard than common Inca agricultural terraces, for instance, they have higher walls made of cut stones instead of rough fieldstones. This type of high-prestige terracing is also found in other Inca royal estates such as Chinchero, Pisaq and Yucay

View across the terraces Ollantaytambo

View across the terraces Ollantaytambo

A set of sunken terraces start south of Ollantaytambo’s Plaza de Armas, stretching all the way to the Urubamba River. They are about 700 meters long, 60 meters wide and up to 15 meters below the level of surrounding terraces; due to their shape they are called Callejón, the Spanish word for alley. Land inside Callejón is protected from the wind by lateral walls which also absorb solar radiation during the day and release it during the night; this creates a microclimate zone 2 to 3°C warmer than the ground above it. These conditions allowed the Incas to grow species of plants native to lower altitudes that otherwise could not have flourished at this site.

The unfinished structures at the Temple Hill and the numerous stone blocks that litter the site indicate that it was still undergoing construction at the time of its abandonment. Some of the blocks show evidences of having been removed from finished walls, which provides evidence that a major remodeling effort was also underway. It is unknown which event halted construction at the Temple Hill, likely candidates include a war of succession, the Spanish Conquest of Peru and the retreat of Manco Inca from Ollantaytambo to Vilcabamba.

At almost the opposite end of the valley, much nearer to Cusco, lies the citadel of Pisaq which lies atop a hill at the entrance to the valley.

The ruins are separated along the ridge into four groups: P’isaqa, Inti Watana, Qalla Q’asa, and Kinchiraqay. Inti Watana group includes the Temple of the Sun, baths, altars, water fountains, a ceremonial platform, and an inti watana, a volcanic outcrop carved into a “hitching post for the Sun” (or Inti).

The angles of its base suggest that it served to define the changes of the seasons. Qalla Q’asa, which is built onto a natural spur and overlooks the valley, is known as the citadel.With military, religious, and agricultural structures, the site served at least a triple purpose. Researchers believe that Písac defended the southern entrance to the Sacred Valley, while Choquequirao defended the western entrance, and the fortress at Ollantaytambo the northern.

Inca Pisac controlled a route which connected the Inca Empire with the border of the rain forest. The Inca constructed agricultural terraces on the steep hillside, which are still in use today. They created the terraces by hauling richer topsoil by hand from the lower lands. The terraces enabled the production of surplus food, more than would normally be possible at altitudes as high as 11,000 fee