Some of the political absurdities that we now have to wade through as part of the brexit discussions or debate.

The UK trade secretary would break the law if he did his job

After he took the role of international trade secretary, Liam Fox boasted that he would have “about a dozen free trade deals outside the EU” ready for when Britain left. But it is of course illegal for Britain, as an EU member state, to negotiate bilateral trade deals. Fox later quietly backtracked on his promise. No one knows what he’s doing with his time at the moment.

Theresa May’s promises on food labelling are straight outta North Korea

In a speech at the Conservative party conference, May promised that Britain would now control how it labels food. But these rules have nothing to do with the EU. They come from a general code at the World Trade Organisation (WTO). For May to deliver on this promise, she would have to adopt the North Korean model of total isolation. She either didn’t know what she was saying was nonsense, or didn’t care.

Eczema sufferers should worry

If you want to sell pharmaceuticals in Europe, they have to have been cleared by European regulators. While we’re in the EU, that’s the case for the UK too. But what happens after we leave? Will a British regulator take up the slack? A fast, hard Brexit of the type being demanded by some Tory MPs would leave a window between leaving the EU and setting up our own regulators. During that period, drug firms wouldn’t be able to get their products authorised for the UK market, so, for a while, there would be no new eczema creams, asthma inhalers or any other new treatments available to British patients.

The government is pretending bad news doesn’t exist

Directors of trade bodies – many of them facing economic and regulatory disaster – went in to brief David Davis when he was made Brexit secretary. But before they got to his office they were taken to one side by civil servants and advised to go in saying Brexit was full of “opportunities”. Anyone who didn’t tended to be asked to leave after five minutes.

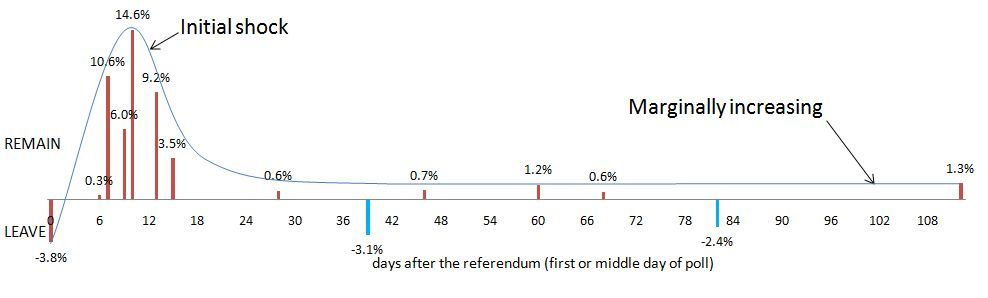

Most people aren’t that fussed about freedom of movement

If there’s one thing everyone accepts the Brexit vote demonstrated, it’s that people want to end freedom of movement. Except this isn’t true. Poll after poll taken during and after the campaign found that between 20% and 40% of leave voters either support immigration or prioritise the economy over reducing it – or just want to remain in the single market.

We need an army of trade negotiators. We barely have a platoon

Or at least we didn’t when we voted to leave Europe. Whitehall is now on a massive recruitment drive. We urgently need an army of general trade experts and ones with specialist knowledge in areas such as intellectual property law. The costs are painfully high. Some are quoting day rates of £3,000 to do consultancy work for the UK government. If they are hired full-time, their salaries will be lower – probably around the £100,000 mark.

Banks will have a good excuse to sack people

City bankers don’t have time to sit around waiting to find out what May’s Brexit plan is. In order to avoid losing passporting rights in Europe, they have to register an office with regulators on the continent – a process that could take years. They are therefore likely to make “no regret” decisions, meaning they will do things they wanted to do anyway. In this case, that means moving back-office administrative staff to locations with cheaper rents and lower salaries, such as Warsaw. The less you earn, the more likely you are to be affected.

The frontline of Britain’s battle with Europe could move from Brussels to Geneva

Brexiters argue that if we don’t get a good deal from the EU, we can fall back on WTO rules. They couldn’t be more wrong. The EU is a member of the Geneva-based WTO too. If the UK tries to unilaterally separate its trade arrangements from the EU without getting its agreement first, Brussels can trigger a trade dispute. For Britain to secure a decent relationship with the WTO, it needs to make sure it is on good terms with the EU.

There are no rules for what Britain is doing because no one has been stupid enough to try it

If Britain does pursue a hard Brexit, things get murky. There are no rules on how an existing WTO member leaves a customs union, because no one has ever been crazy enough to try it. Lawyers at the organisation are trying to sort out how this works and what the process will be.

Britain is going to pretend it’s still in the EU (don’t tell anyone)

If Britain is to going to ensure stability during its transition from the EU to independent membership of the WTO, it will have to replicate all the EU’s tariffs (charges on imports and exports). This makes a mockery of everything Brexit stands for, of course, but if we changed any tariff, it would trigger an avalanche of trade disputes and lobbying operations. If Britain was to raise tariffs on ham, for instance, it would trigger protests and formal dispute claims from not just European ham producers, but those all over the world.

The UK steel industry could collapse overnight

There’s an EU agreement at the WTO preventing China from dumping cheap steel in Europe. Without it, plants such as Port Talbot would collapse as Chinese product flooded the market. When Britain leaves the EU, it will claim that it is still a signatory to this agreement and the Chinese will object. This dispute is likely to last for years. If Britain loses, it will likely lose its domestic steel industry.

You can’t just copy and paste EU law

Ministers want to transfer all EU laws into Britain using the so-called great reform bill. The trouble is, they don’t know where to find them. The Equalities Act, for instance, is a messy mixture of EU and UK legislation. In every area of law, there are bits and pieces of EU directives. Good luck tracking them all down.

Article 50 isn’t actually a trade deal

Leaving the EU involves three things: an administrative divorce, the untangling of British and EU law, and (probably) a new trade deal. But only the first aspect is dealt with in article 50. The rest is up to Europe’s discretion. If they want to just talk admin, we can’t do much about it.

British divorcees in Europe may become half-married

If European countries don’t like the way article 50 talks go, they could decide to not recognise legal decisions from London. At a snap, British divorcees who live in Europe would suddenly find themselves in a state of marital limbo – with their home country recognising their divorced status, but their adopted country considering them married.

Britain (and its tabloid press) could end up demanding a hard border with Ireland

Britain and Ireland enjoy legal protections against EU immigration law which allow them to “continue to make arrangements between themselves relating to the movement of persons between their territories”. This should prevent Brussels imposing a hard border for people in Ireland. But there are no protections against tabloid scare stories. After Brexit, we can expect campaigns about Polish plumbers crossing into England from Ireland to work. It will be nonsense – Polish people could just as easily use tourist visas – but it could be politically effective. If a hard border returns to Ireland, it will be because of Britain, not the EU.

Screwing up trade with Europe = screwing up trade with the world

Leaving the single market will sever Britain’s relationship with its largest trading destination, but the problems don’t end there. Europe also has agreements with other major economies such as the US and Japan allowing it to transport goods without expensive and slow border checks. If Britain leaves the single market, we’ll lose these too. Oops.

What’s good for the burger lover isn’t good for the beef farmer …

A bilateral trade deal with the US would see cheaper burgers in the UK. The Americans have lower animal-welfare standards, use growth hormones in their meat and have larger farms. This won’t be good news for British farmers, who will also be facing sky-high export tariffs and a possible end to subsidies. And it won’t be good news for animal rights campaigners. But burger lovers might be pleased.

… not to mention British vets, who don’t enjoy watching cows being slaughtered

EU law insists on an independent veterinary presence in abattoirs. The problem is that 95% of the vets doing this job in Britain are European – most of them from Spain. The problem is one of demand. British vets study for years to cure family pets, not watch cows being slaughtered. But Europeans have less of a cultural hang-up about that type of thing and are also willing to accept the lower wages involved. If Britain doesn’t train up more domestic vets for the abattoirs, it won’t be able to sell meat to Europe or properly check it for disease.

Our battered fish isn’t actually our battered fish

British fishermen want the UK to prise open the incredibly complex European system for allocating national quotas of fish stocks and renegotiate the whole thing. That will take a long time and a lot of manpower. If they get it wrong, the UK could face problems. The type of white meat we like for fish and chips doesn’t actually come from the UK – most of it comes from the seas around Norway and Iceland.

Britain may be about to adopt lower US standards on … everything

The Americans have lower consumer standards than Europe on pretty much everything, from chemical safety to data protection. A bilateral trade deal will see them demand we lower our standards so their products can enter our market more freely. Given how desperate we’ll be, we’re likely to comply.