The reason for visiting Bolivia is the salt flats near Uyuni. Visit them during the rainy season and you end up with pristine pictures of mirror reflections. And very wet feet.

Visit during the dry season and you end up with endless vistas of white against a blue sky and sun so blinding you can’t actually see anything without glasses.

The views are so blinding that without a filter on a lens, you have to guess where the horizon lies and end up with ridiculously wonky photographs.

The tourist routine is fairly straightforward: fly down to Uyuni early in the morning an collect a four wheel drive jeep to take it out onto the “lake” of salt. Around the start point, the tracks of the cars are obvious.

But that soon changes. It becomes almost impossible to gauge distance as everything tends to blur into the white and of course at that altitude the sun is strong and blinding.

Originally a sea, the tectonic upheavals lifted it high and dry. Overtime the rains arrive, they effectively lift a layer of salt to the surface such that at it’s thickest, the rock salt is now almost 5m thick.

Underneath, there are rivers of cold water that occasionally bubble to the surface

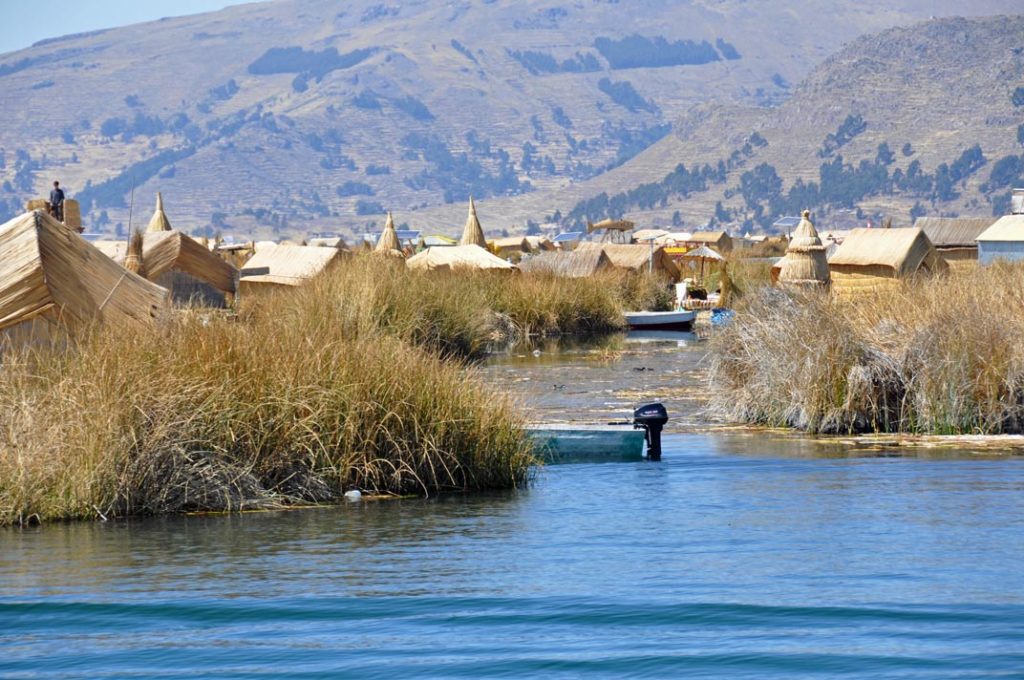

Around the edge are the “islands” with the island of the moon in the middle.

Originally there would have been small farmers of the salt but mostly these have been replaced by companies on a more industrial scale. A few small holders remain, mainly for the tourist trade.

And there are the businesses that cut rock salt from the surface to make bricks for the various salt hotels set up for tourists.

The surface of the plain is broken into geometric patterns where the crystalline rock salt has come together over time.

Close to, the surface is a funny mix of almost cubes.

As well as the salt itself, we headed towards the main island, the volcano.

Climbing just slightly, and slowly because this is at very high altitude, we reach a series of caves where over the generations people have left their dead to mummify over time, essentially desiccating very very slowly because of the salt.

There were both male and female adults, plus some very forlorn corpses of babies.

Looking back down at the salt, it almost looks like clouds with mountains peaking up from below.

And down at the bottom, flamingoes and llamas.

And some small collections of salt for the locals.

Towards sunset and we head towards the centre to try to catch the changing colour of the plain.

And all totally silent.

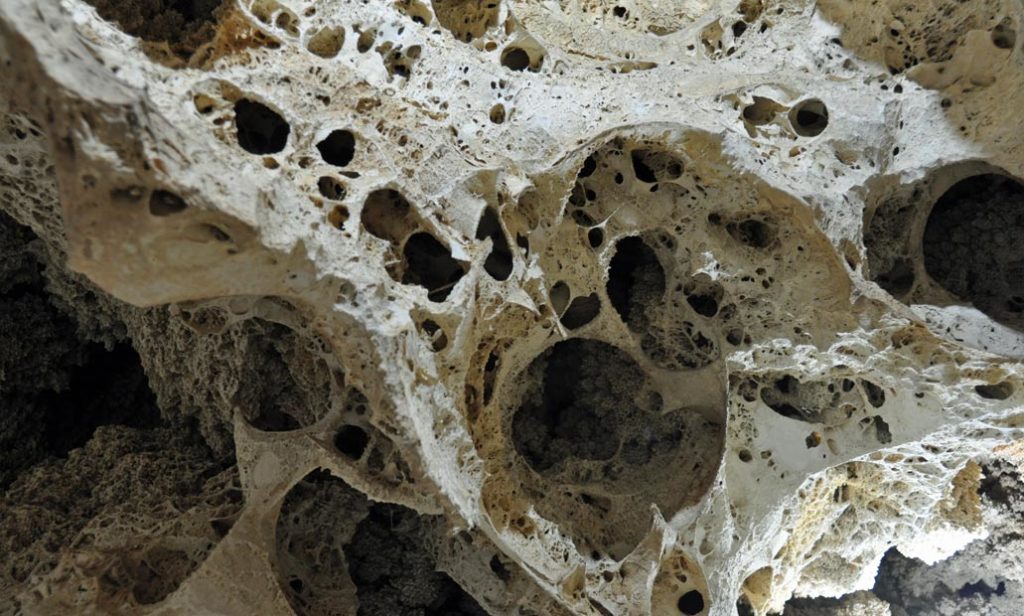

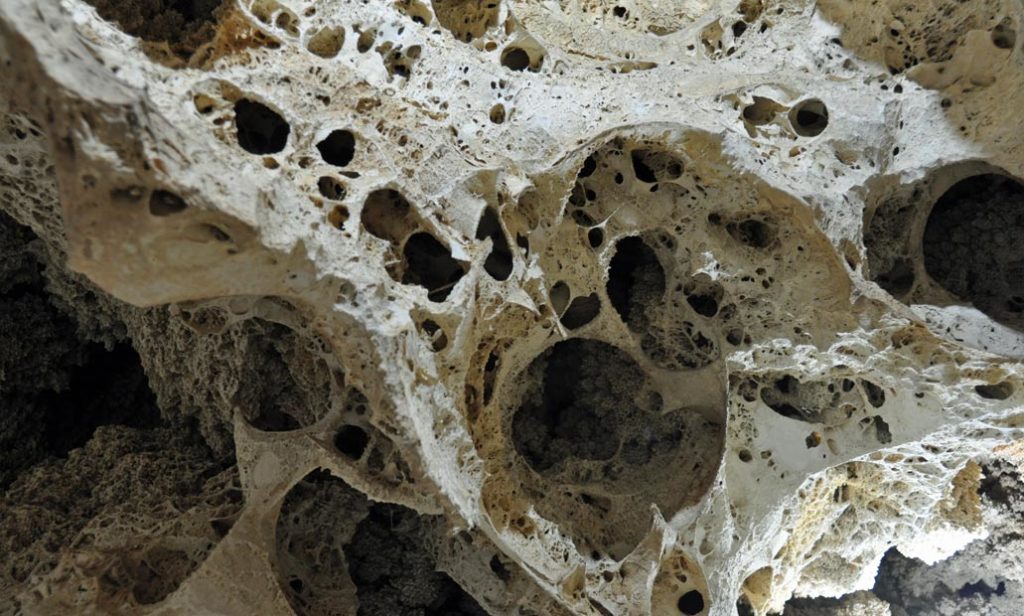

For the next day we headed to some caves on the other side of the salt plain, where the petrified remains of coral caves have been discovered.

It is one of the freakiest places I’ve been inside, like walking around inside an insect or maybe an alien’s nest and just expecting any minute that something horrid will jump out and eat you.

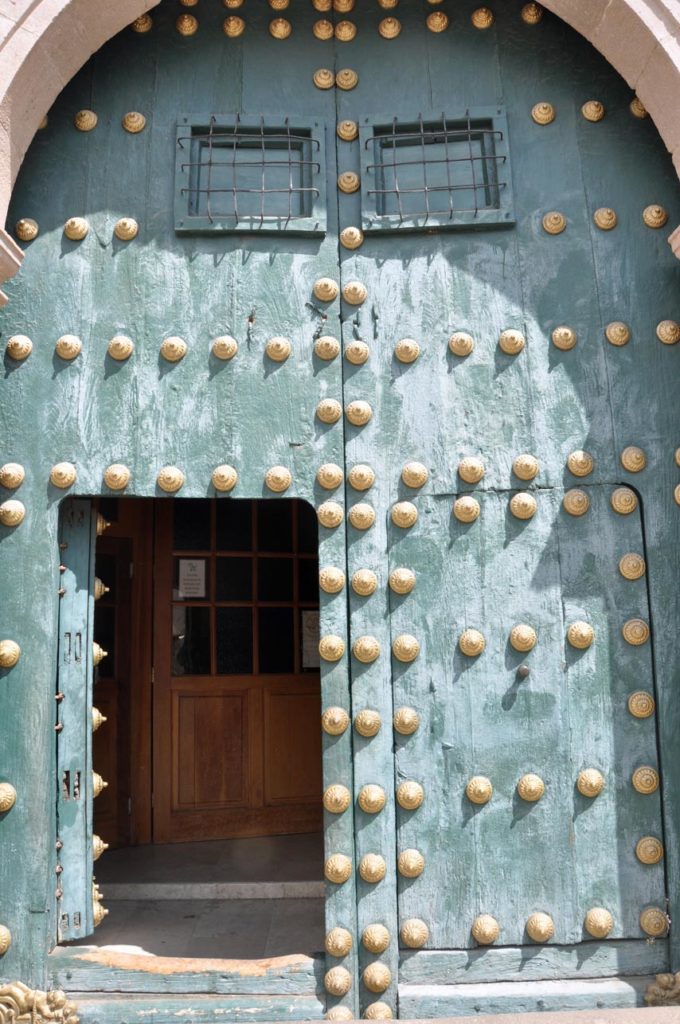

And the around the corner to another set of burial caves and that strange mix of catholicism and something altogether older and darker.

The wild vicuna most certainly regarded us as interlopers.

And it’s difficult to imagine how they might survive in such a harsh environment.

In the middle of the plain is the island of the moon, with cacti taller than a man.

The only building material is the “wood” of these huge cacti, dried out and cut into planks.

It is almost impossible to capture the scale of the place, even knowing that the view below includes jeeps, something just refuses to accept they can be that tiny.

And lying above it all, that blue blue sky.