Apparently I wrote too much in 2016, and the resulting fatal error” memory crash, means a second page in necessary.

July

BooHoo

In true Machiavellian mode, Michael Gove, Brexit campaigner has just stabbed his co-conspirator Boris Johnson (BoJo) and has announced his own candidacy for Prime Minister of the UK.

As BoJo’s campaign manager, Michaell Gove’s suggestion that Boris simply wasn’t good enough and could not be trusted to lead the country was a devastating blow.

And all of this was used to explain why he had to be the candidate instead of BoJo (Gove’s thunderbolt and Boris’s breaking point: a shocking Tory morning). The TV series “House of Cards” seems sensible in comparison.

At the same time the leader of the opposition, Jeremy Corbyn is under siege and refusing to stand aside. In order to challenger him, an MP needs the backing of 20% of Labour MPs and MEPs. Currently, there are 229 Labour MPs and 20 MEPs. Party officials are still debating whether a candidate needs 50 or 51 signed-up supporters but there are definitely people able to command that level of support. Angela Eagle, ex-shadow business secretary, was expected to declare that she was going to run as a “unity candidate” at a 3pm press conference yesterday but has put it off waiting for the Conservative furore to pass.

It is also unclear whether Jeremy Corbyn’s name would automatically be on the ballot paper – which is crucial because Corbyn would struggle to gain 50-51 names willing to re-elect him as leader.

He claims to have the support of Labour Party members, all 200,000 of them. Nine months ago he received 59% of the party vote. However the most recent YouGov poll for the Times, carried out entirely after the Brexit vote last Thursday, shows that opinions are shifting fast – his net job approval is reduced to +3, down from +45 just last month.

Amongst those who voted for an “Anyone but Corbyn” candidate last year (Yvette Cooper, Andy Burnham or Liz Kendall) eight in ten think he should step down as leader straight away. Amongst the 59% who supported Mr. Corbyn, six in ten think he should stay on and fight the next general election.

As things currently stand, were Mr. Corbyn was on the ballot paper again, 36% say they would definitely vote for him (down from 50% in May) and 36% say they definitely wouldn’t vote for him (up from 22%).

In a hypothetical head-to-head matchup between him and Angela Eagle, he currently holds a 10 point lead at 50% to 40%, with 5% saying they would not vote and 7% saying they don’t know. The poll was solely made up of full party members. Like last year, it is possible for any member of the public to get a vote in a leadership election if they pay a £3 fee. Members of affiliated trade unions can also opt in to voting.

In an email, the Parliamentary Labour Party’s director of political services, Sarah Mulholland, writes: “It is clear that some of our MPs are currently experiencing abuse and threats. As per the security briefings, this information should be passed to the police immediately.”

Vicky Foxcroft, the MP for Lewisham Deptford, revealed that she had been threatened with violence if she refused to back Corbyn; Lisa Nandy said that colleagues had been bullied and harassed; while John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor and staunch Corbyn ally, responded to complaints by urging supporters not to protest outside MPs’ offices.

So I’m beginning to re-think my views on Corbyn as a gentle, decent man. How kindly can he be if he’s willing to send out the bully-boys to MPs who disagree with him? How hard is his team working to keep his cult followers under control?

Corbyn’s supporters argue that, as the incumbent, he would automatically be on the ballot paper in the event of a challenge, with the prospect he could again mobilise the grassroots activists who propelled him to the leadership last year.

If he resigned, however, allies such as McDonnell might struggle to get the nominations they need to enter the leadership race.

There were further calls for Corbyn to quit, with a letter signed by 540 Labour councillors posted on the LabourList website saying he was “unable to command the confidence of the whole party, nor of many traditional Labour supporters we speak with on the doorstep”.

Useful

Often when I’m visiting my friend W and his wife, we are interrupted by a young man who arrives for his piano lesson. W’s wife makes her excuses and off they go.

This young man is an exceptional person in many ways. He comes from an Armenian family, speaks three or four languages fluently, is academically very successful and seems to have negotiated his parent’s divorce and remarriages with grace. He volunteers with the St John’s Ambulance, a service that offers paramedic support at public events.

When asked what his ambitions are for the future, he talks about pursuing a career as a paramedic, a first responder. When asked about his mother’s ambitions for him, he looks wry. As any good mother, she wants her son to do as well as he can. She’s ambitious for him and wants him to train to be a doctor.

Obviously both paramedics and doctors help people. They are professions where, at their best, one serves and saves other people.

Both professions now require a university degree. The academic requirements for a paramedic course are lower, but since he’s an academic kid that’s not a concern. The salary of a doctor is likely to be higher than that of a paramedic but the latter are not badly paid.

The career of a paramedic used to be quite limited to in-house ambulance Trust training or management roles. In recent years however, many paramedics have developed their clinical practice into specialist and advanced roles in areas such as primary and critical care. Increasingly paramedics are to be found working for institutions other than ambulance Trusts, such as Out of Hours GP providers, Minor Injuries Units, Walk-In Centres, and various private health providers, both in the UK and abroad.

The reasons he enjoys his work as a volunteer paramedic are the reasons he wants to pursue it as a career. He enjoys helping people. He enjoys the immediacy, the direct interaction with people in need, the immediate validation that successful outcomes bring him. He enjoys the adrenaline spike that arrives when dealing with emergencies.

And whilst all of these things can be found in certain roles for doctors (A&E is the most obvious) he also enjoys the idea of being a generalist rather than being asked to specialise as early as doctors must. He expects the life of a paramedic to be exciting and fulfilling. When he gets “old” and the role becomes too stressful, he sees himself stepping back and moving into managing teams of paramedics.

Whatever he ends up doing with his life, this young man will be a credit to his mother.

With my two girls heading off into the world of higher education, neither with any clue what they’ll end up doing with their lives, it makes me wonder. There is ted talk that asks: What’s the most satisfying job in the world? You’d be surprised.

It turns out that the lesson from the various people and occupations discussed is that virtually any job has the potential to offer people satisfaction. Jobs can be organized to include the variety, complexity, skill development, and growth that we all look for in our lives. They can be organized to provide the people who do them with a measure of autonomy.

But perhaps most importantly, they can be made meaningful by connecting them to the welfare of others.

Cancer

For most countries, the general health development pattern is one of reducing deaths due to child mortality, reducing deaths due to communicable diseases and reducing gender imbalances in health outcomes and mortality. But this has been accompanied by a shift towards a larger share of the remaining deaths caused by non-communicable disease and injuries (NCD) such as cancer.

As people live longer, the pattern of mortality changes and NCDs become more significant. As we age, cancer rates increase, heart disease increases etc. Improvements in treatment have not kept pace with the risks associated with our longer lives.

This is not just an issue for the developed world.

At a highly successful meeting to discuss the future of maternal health, held in January, 2013, in Arusha, Tanzania, one doctor from Zimbabwe pointed out that although it was completely correct to place the highest possible priority on health outcomes for women during pregnancy and childbirth, she was horrified at the neglect still shown towards other causes of women’s ill-health — eg, hypertension, stroke, cancer, and asthma.

She saw women daily in primary care clinics with these conditions, yet she also saw no serious commitment by donors or countries to create programmes to address these diseases and their risk factors.

In her opening address to this same conference, the Minister of Health for Rwanda, Agnes Binagwaho, noted that cervical cancer now kills more women in the world than pregnancy and childbirth. Last year, The Lancet published work from 27 sub-Saharan African countries showing that maternal obesity had become a significant risk for early neonatal death.

So where are the global conferences on NCDs, the research meetings, the task forces, the grand challenges initiated by funders and foundations? They don’t exist. The global health community, understands that chronic diseases are a present danger to the health of our societies, yet are apparently unable to translate that understanding into real political action.

It seems politically difficult to put heart disease, stroke, cancer, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes, or mental ill-health, together with their associated risk factors, on an equal footing with childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea, preventable maternal death, or epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. The disconnect between the reality of people’s lives in countries and the concerns of professional and political leaders has rarely been greater.

We are stuck with a Victorian world-view of death and disease.

Globally deaths from cancer rose from 5·7 million in 1990 to 8·2 million in 2013, according to the latest data from the Global Burden of Disease Study. This 46% increase—one in seven deaths worldwide from cancer-related causes—explains why cancer has risen quickly to the top of the global health agenda.

The underlying rising incidence of cancer is outpacing the improved cancer survival seen over the past 5 years, and recent data from CONCORD-2 shows the large inequalities and differences that exist between countries. On Jan 1, 2016, the Sustainable Development Goals were announced. Addressing the cancer epidemic will be a key part of achieving these goals.

There is already an ambitious target for the international community to meet: a 25% reduction in premature deaths from non-communicable diseases by 2025.

Cancer is a critical part of this commitment—expressed, for example, as a 30% reduction in tobacco use and an 80% availability to essential medicines.

Unfortunately, the obstacles to dealing with the increase in NCDs are great and largely undiscussed, thanks to their deep political sensitivity. It remains a truth today that, despite global rhetoric and resolutions, chronic NCDs remain the least recognised group of conditions that threaten the future of human health and wellbeing.

Union

There’s an interesting blog by the LSE looking at how a compromise might allow the United Kingdom to survive whilst allowing for Scotland, Ireland and Gibraltar to remain within the European Union.

England and Wales have voted to leave the European Union, but Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Gibraltar have voted to remain. These differing outcomes have to be the central focus of political attention while we wait for the debris of broken expectations to settle.

Those who insist that a 52-48 vote is good enough to take the entire UK out of the EU would trigger a serious crisis of legitimacy.

Is there is a constitutional compromise that would avoid the genuine prospect that a referendum on Scottish independence – promoted by the SNP and the Green Party – will lead to the break-up of the union of Great Britain. The Scots have every right to hold such a referendum, because the terms specified in the SNP’s election manifesto have been met: a major material change in circumstances has occurred.

The same compromise would need to diminish turbulence spilling into Northern Ireland. The same day that Nicola Sturgeon publicly indicated preparations for a second Scottish referendum, the Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, Martin McGuinness (Sinn Féin), demanded that a poll be held to enable Irish reunification.

Sinn Féin has a point. Many in Northern Ireland fear that a UK-wide exit would restore a border across Ireland, and strip away core components of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. Does the narrow outcome of a UK-wide referendum automatically over-ride the terms of the Ireland-wide referendums of 1998, and a majority within Northern Ireland?

It would be perfectly proper to call for a border poll to give people the option of remaining within the EU through Irish re-unification – especially if there is no alternative that respects the clear local majority preference to remain within the EU.

The very same compromise may also weaken the pressure from the Spanish government for the UK to cede sovereignty over Gibraltar.

The compromise would have to be that the bulk of the UK would be outside -‘externally associated’ perhaps – and some of it inside the EU.

Is this possible?

Many UK dependencies – including three members of the British-Irish Council, Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man – are currently not part of the EU. It’s already the case that sovereign states, including the UK, have parts of their territories within the EU, and parts of them outside.

The terms of the foundational treaty, the Treaty of Rome, also envisioned associate status: they were designed for the UK. Also, consider past precedent. Greenland, part of Denmark, seceded from the EEC, but Denmark remained within the EEC.

Of course, the components of the UK that remain within the EU would not be entitled to the same rights that currently are held by the UK as a whole.

Negotiating a UK-wide exit is not going to be easy for the next Prime Minister and Cabinet.

The consensual solution would be to negotiate for the secession of England and Wales from the EU, but to allow Scotland and Northern Ireland to remain – with MEPs, but without representation on the Council of Ministers, though with the right to have a single shared commissioner.

To work, this compromise requires part of the UK to remain within the EU and for those to require representation inside the EU’s institutions. Retaining MEPs in Scotland and Northern Ireland would be easy. They would be numbered as proportional to population and this would have no major implications for the big states. The now vacated UK Commissioner’s role could be kept, but the appointment could be rotated between Scotland and Northern Ireland, in a 3:1 ratio over time, reflecting Scotland’s greater population.

The Commissioner would be nominated by the relevant government and appointed by the UK government. (A judge to serve in the European Court of Justice could be nominated in the same way.) The retention of one Commissioner and their MEPs would give Scotland and Northern Ireland a say in agenda-setting and law-making. And it would remove any UK ministerial veto over EU decision-making.

The future role of Westminster would be to process EU law that applies to Northern Ireland and Scotland – strictly as an input-output machine – thereby ensuring that Scotland and Northern Ireland have the same EU law, and that the Union is retained. It would be up to Westminster to decide which components of EU law will apply to England and Wales – a convenience that may be helpful in dealing with the repercussions of what has just occurred.

The currency is a reserved Crown power, and the proposed compromise would not lock Scotland and Northern Ireland into the Eurozone. Rather as part of the UK, Scotland and Northern Ireland should inherit the entire UK’s position under the Maastricht treaty (stay with sterling unless the UK let them adopt the Euro).

All of Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales would be an internal passport free-zone but there would need to be a hard customs border in the Irish Sea. That would have to be better than one across the land-mass of Ireland.

Another effect would be a hard customs border between Scotland and England. If all of Ireland and Scotland remain in the EU there cannot be a single market in the UK, as defined by the EU, and therefore a customs barrier will have to exist. But a hard customs border will materialize in any case if a Scottish referendum led to independence.

Ireland, North and South, and Scotland could not join the Schengen agreement because that would mean that England and Wales would lose the control over immigration which was emphasized by the leave side in the referendum. But then, they are not part of Schengen at present, and there is no evidence that a majority in any of the three countries wants to be.

Would there be any other benefits to this idea, aside from keeping the UK together? UK enterprises could re-locate to EU zones within the UK, which would soften the negative consequences of an entire UK exit. These arrangements would leave England and Wales to experiment with whatever policy freedoms they preferred.

Citizenship and migration-law would have to be reconsidered, but the ensuing difficulties could be negotiated. These matters will be on the table anyway.

Going forward, the collective ingratitude and contradictions of nations and states should never be underestimated. Consider, for instance, the vote in Wales, which has been undeniably a net beneficiary of the EU, while its devolved leadership has already said that it will want to renegotiate the Barnett formula.

Some constitutional reconstruction of the UK is therefore necessary. The starting question to be posed to Conservative and Labour leaders, and to the UK Parliament, is whether the Welsh and the English believe that the first cost of taking back control of their own affairs should be the imposition of control over Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The interests of states in making bargains and treaties are rarely based on profound generosity. The divorce agreement that the Leave side will seek to negotiate has to be acceptable to the existing member-states of the EU, or else there will be a chaotic UK departure without agreement.

And so the new Cabinet that will negotiate with its European counterparts will soon realize that the Irish and Spanish states have a veto power over the divorce agreement – and any subsequent ones. Spain and Ireland are not alone. There will be many states with an interest in protecting their stranded ‘diasporas’, not just the flow of capital, goods and services.

And don’t forget about the United States. Anyone who imagines that a UK-US trade agreement will get easily get through the American Senate has limited knowledge of US treaty-making. It will not matter whether Clinton or Trump is in the White House: as Obama has warned, the UK will be “in the back of the queue”. The constitutional compromise suggested here will calm the UK’s domestic politics, and give the EU a continuing stake in some of the UK.

Health

The Lancet magazine recently published a table showing the expected change in health spending per country in 2040 and it predicts that all countries will be obliged to spend considerably more than now as might be expected from an ageing population.

It also highlighted the large difference in cost across wealthy countries in the past, now and in the future.

In the UK, we spend relatively little on healthcare (2013 figures) at just 9.1% GDP compared to similar European countries such as France (11.7%) or Germany (11.3%). Certainly we spend considerably less than the US at 17.1%.

The cost of healthcare in the UK is predicted to rise to 11.1% in 2040, France (14.7%) Germany (14.2%).

It predicts that the cost of healthcare in the States will rise to 23.4% by 2040 ie. costing almost $1 out of every $4 earned.

Given that the mortality rates across these developed countries is much the same, UK (80.4) France (81.7) Germany (80.7) USA (78.9) one has to wonder what on earth the Americans are spending their money on. (World Mortality Report 2013)

Diabetes

A friend’s son has recently developed Type 1 diabetes despite having no family history of the disease.

He’s not unusual.

Over the last 30 years there has been aincrease in the disease, one that cannot possibly be explained by genetics alone. According to a recent report in the Lancet, and subject to considerable controversy, environmental factors may contribute towards developing the disease.

Read the full Lancet Risk factors for type 1 diabetes series:

The Lancet: Risk factors for type 1 diabetes

Shame

Sometimes rich liberal countries, even liberal well-intentioned ones have things they’d rather not talk about.

A recent article in the Lancet focused on suicide in Canada, specifically suicide amongst the indigenous community, the Innuit.

Speaking at a conference on Indigenous health issues in Toronto in late May, Natan Obed, leader of the 60 000 Inuit who lay claim to a third of Canada’s vast landmass, reprised his people’s plight:

- shortened life expectancies;

- a high infant mortality rate;

- high rates of tuberculosis;

- widespread food insecurity;

- dangerously inadequate housing; and,

- shockingly deficient local health care.

According to the Canadian Government, suicide rates in the four Inuit regions are more than six times higher than the rate in non-Indigenous regions. Among Inuit youth, suicide is responsible for 40% of deaths, compared with 8% in the rest of Canada.

But as Obed noted, these figures—which are drawn from Canadian Government data that include non-Indigenous as well as Inuit people living in Canada’s far north—substantially misrepresent and understate the problem.

The true suicide rates of the indigenous population are likely to be much worse.

According to a 2015 report commissioned by the Inuit, 27% of the deaths deemed in coroners’ reports to have been suicides by Inuit people between 2005 and 2011 are missing from the figures relied on by the Canadian Government. According to study author Jack Hicks, this means that the Inuit suicide rate is 11 times the Canadian average—or 55% higher than the Canadian Government acknowledges. And in one lightly-populated Inuit region, the suicide rate is roughly 25 times the Canadian average, Hicks says.

At the very least, all this statistical confusion reveals a lack of government concern.

As Isadore Day, head of the health committee of the Assembly of First Nations, the national political group that represents 900 000 Indigenous Canadians, told the Toronto gathering, suicide—both threatened and completed—has become a tragic marker for a broader array of health crises among Indigenous Canadians.

“There’s a temptation to want to focus on the suicide issue”, Day told The Lancet. “But we have to look at the root causes. And those all have to do with the social and economic conditions in Indigenous communities with high suicide rates.”

For Obed, the suicide crisis is rooted in a group of risk factors including:

- Inuit people are eight times more likely than other Canadians to live in overcrowded homes.

- “Many of our households do not have enough to eat”, he added, “and that has a huge impact on mental and physical health.”

- The Inuit also lack access to basic health-care facilities and addiction treatment programmes, Obed said.

- Add to that very high rates of mental trauma rooted in forced resettlements, forced residential schooling, and high rates of sexual abuse and childhood adversity, Obed noted, and, “if you are Inuit, chances are you are growing up in a community with high risk factors for suicide”.

Canada’s federal and provincial politicians have pledged their concern and promised to help with emergency programmes targeting youth at risk for suicide. But short-term stopgap measures are unlikely to make a lasting difference, given the underlying causes identified says Perry Bellegarde, national chief for the Assembly of First Nations. Bellegarde has called for a national strategy similar to that crafted by the Inuit.

Manosphere

From the outside looking in, it would seem to me that men and boys generally have a much greater and better range of choices than their mothers, sisters and daughters. Do we really think that boys should be given a 5% head start in every exam, to even the grades?

Reproductive choices seems to be interpreted rather narrowly as the choice to avoid financially supporting their kids, even of forcing an abortion on a woman to avoid having kids.

Wouldn’t it be easier to wear a condom or get a vasectomy than force major surgery on someone?

Observers of the manosphere disagree over exactly what fuels it. Barbara Risman, the head of the sociology department at the University of Illinois at Chicago, attributes its rise to a fear that as women become more liberated, men are struggling with feeling dispensable. “Previous men’s movements dealt with an expansion of the idea of what men could be. This is different. This is about men feeling as though they’ve lost dominance.”

After finding the manosphere I started to look around for the femosphere, a feminist space on the internet. The best I could come up with was a rag-tag collection of the “best sites for women” which were in no way comparable to the manosphere.

There are magazines with a varying mix of lifestyle and political articles, most of which are US focused. These might include: Blogger, Jezebel, Feministing, Mic.com, Rewire, Everyday Feminism, Think Progress, Ms. Magazine

And then there are the practical sites that connect people or issues together: The Women’s Room, Lean In, The Fementalists, Women Like Us

Looking through these and others, I didn’t find anything like the anger of the manosphere. In general, the women’s sites seemed to quite like men, seemed to value their fathers, partners and sons. There was lots of intersectionality, support for LBGT communities. In general they were happy or at least constructive places.

It seems perverse that the 48% of the population that enjoys such privilege should be so upset about it.

Rise and Fall

BLACKPOOL in its heyday was everything a mill worker or clerk could wish for in a holiday resort. There were piers and beaches, the outdoor dancing stages and the music halls, ludicrously extravagant Moorish and Indian follies where entertainers from Laurel and Hardy to Frank Sinatra delighted the crowds. And there was the Tower, modelled on Eiffel’s in Paris, with its lights, ballroom and mighty Wurlitzer organ.

One in five Britons holidayed in the town. So the memories of those years lived on long after the dawn of mass foreign tourism in the 1960s. The recent success of “Strictly Come Dancing”, a televised ballroom-dancing contest, is testament to a lingering national soft-spot for its old blend of sequined razzmatazz and Victorian politesse.

Today the memories are almost all Blackpool has left.

Abandoned for the Spanish Costas, Blackpool failed to find a new role, became one of the ten most deprived towns in Britain and is now almost cinematically bleak: Coney Island meets Detroit.

The town centre is a smelly (urine and fried food, with notes of cannabis) patchwork of charity shops, nightclubs with fading playbills and unloved tourist emporia flogging boiled sweets in saucy shapes. In the back streets scrawny men loiter outside terraces of peeling boarding houses, swigging from cans and glaring at the seagulls. “People aren’t usually in Blackpool if they have somewhere to go,” says Brian, an unemployed waiter outside the job centre.

George Osborne, the chancellor of the exchequer has abandoned struggling places like this. Where previous governments, to varying degrees, tried to prop them up, his (tacit) message to their residents is: get on your bike. Move to those places with the connections, industries and profile needed to make it in a globalised economy. Places like nearby Manchester, today a creative- and financial-services boomtown and the crane-dotted pivot of the “Northern Powerhouse”, his grand plan to integrate the big northern cities.

The chancellor wanted the state to concentrate less on solving problems and more on creating the conditions in which places and people succeed as shown by his increases to the minimum wage, his infrastructure spending, his sugar tax and his wave of devolution to cities (none more than Manchester, which he announced would gain new control over its policing).

The corollary of all this is that failing places will be given more latitude to fail.

Blackpool is the local authority which has lost most per person under austerity, because it is so reliant on public spending. Its private economy is weak and seasonal and its people are relatively poor, unhealthy and troubled: one in four claims welfare benefits, life expectancy is five years below the national average and the town has acute crime, drug-abuse and alcoholism problems. Blackpool’s economy shrank by 8% over the five years from 2010.

All of which is making a grim situation worse. The council has trimmed street-cleaning, business and social-care services. New cuts from Whitehall mean some leisure centres and libraries may have to close, warns Simon Blackburn, the Labour council leader.

And Britain’s geographical polarisation is self-perpetuating: as Blackpool slides, its most mobile citizens leave for the big cities (254 well-educated youngsters left between 2009 and 2012, one-third for London) while down-and-outs attracted by low house prices move in (bedsits rent for £70, or $100, per week). The result is a downward spiral towards a future as, in Mr Blackburn’s words, “a refuge for the dispossessed and the never-possessed”.

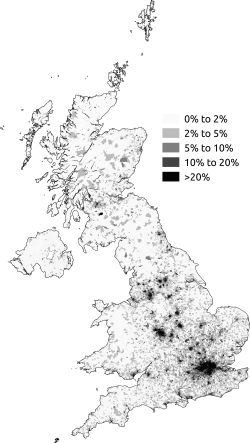

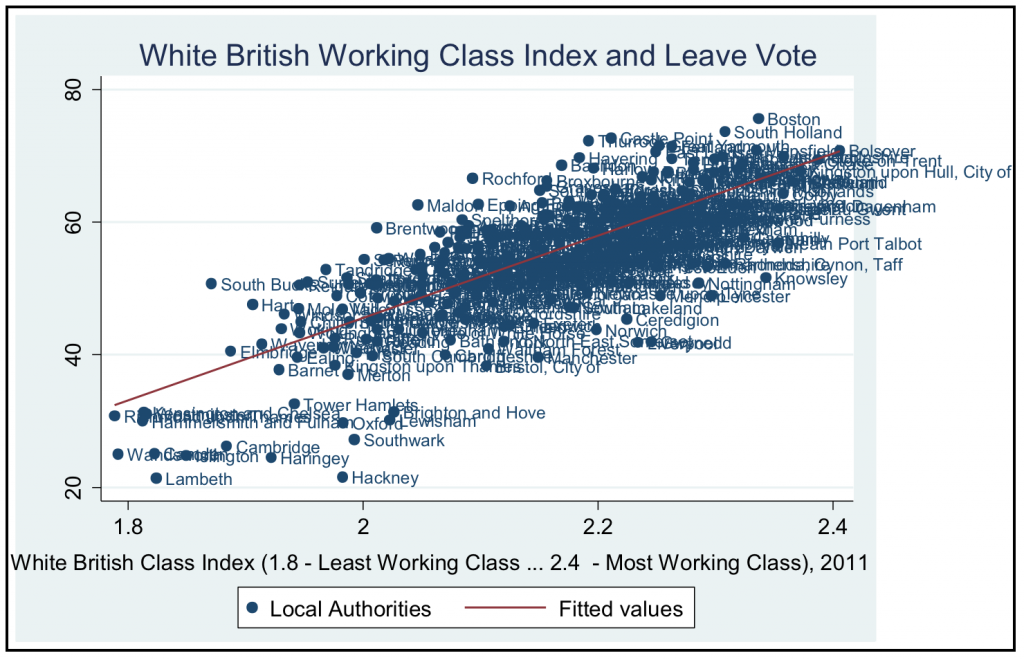

The people left behind tend to older and less qualified. These are not towns that attract immigrants who typically follow work so they tend also to be predominantly White British.

Mr Osborne’s metropolitan revolution responds to the harsh realities of the modern economy and it is a wise use of public money to extend the success of places that have what it takes to grow and be prosperous, and help people elsewhere relocate to where the good jobs are. But one can hold these views and simultaneously regret Blackpool’s fate.

Voters in Blackpool and similar cities and towns around the UK feel left behind and are turning to populist political outlets: last year the UK Independence Party’s share of the vote more than tripled to 15% and 17% in the town’s two constituencies. The people left behind had relatively little to risk in the referendum, having benefitted very little in the first place.

How much will the EU referendum be a referendum about failing Tory policies rather than our membership of the European Union?

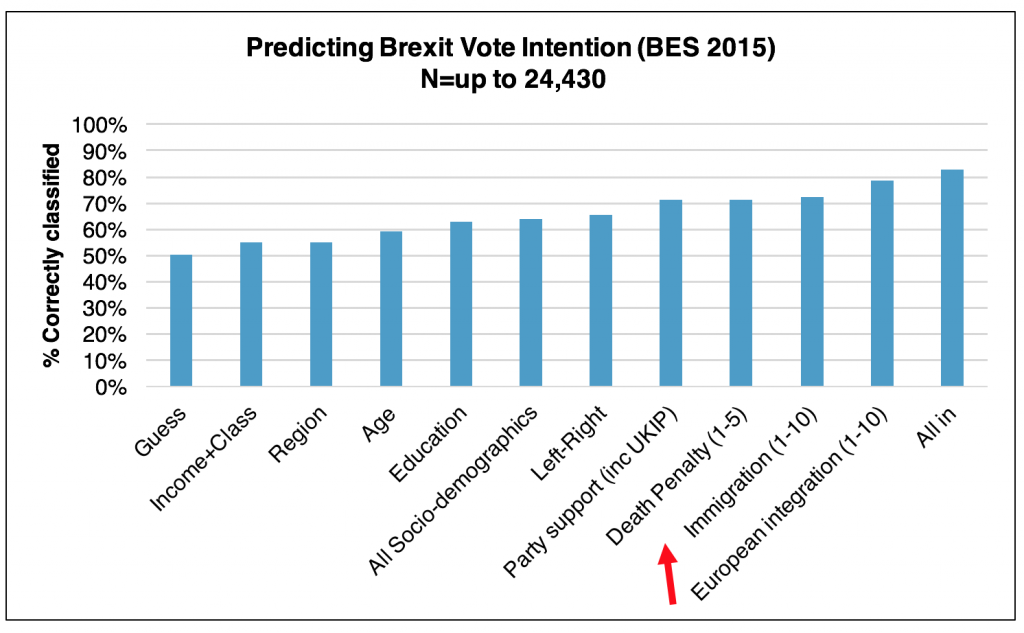

Now we know the answer. Failing towns and cities have uniformly voted to leave the EU either because they (mistakenly) blame the EU for UK government decisions or because they simply don’t care that it benefits other areas, if it fails to benefit them. “Let’s drag everyone down to our level of poverty and misery. Let’s fuck them all”

Alzheimer’s

Every time that I forget something, I worry not just that I am getting old but that I’m getting Alzheimer’s Disease. It’s the paranoia of our age. So of course when someone tweeted that there were positive results in a (very) small study in UCLA I took a look.

The study came jointly from the UCLA Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research and the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, and is the first to suggest that memory loss in patients may be reversed, and improvement sustained. It uses a complex, 36-point therapeutic program that involves comprehensive changes in diet, brain stimulation, exercise, optimization of sleep, specific pharmaceuticals and vitamins, and multiple additional steps that affect brain chemistry.

The findings, published in the current online edition of the journal Aging, “are very encouraging. However, at the current time the results are anecdotal, and therefore a more extensive, controlled clinical trial is warranted,” said Dale Bredesen, the Augustus Rose Professor of Neurology and Director of the Easton Center at UCLA, a professor at the Buck Institute, and the author of the paper.

Bredesen’s therapeutic program for one patient included:

- eliminating all simple carbohydrates (i.e.. sugar) leading to a weight loss of 20 pounds;

- eliminating gluten and processed food from her diet, with increased vegetables, fruits, and non-farmed fish;

- to reduce stress, she began yoga;

- as a second measure to reduce the stress of her job, she began to meditate for 20 minutes twice per day;

- she took melatonin each night, a hormone used in synchronising sleep patterns, and also as an antioxidant, protecting nuclear and mitochondrial DNA;

- she increased her sleep from 4-5 hours per night to 7-8 hours per night;

- she took methylcobalamin (a form of Vitamin B12) each day;

- she took vitamin D3 each day;

- fish oil each day which contains omega3 fatty acids and precursors of certain eicosanoids that are known to reduce inflamation in the body;

- CoQ10 each day, which is also known as ubiquinone and is a component of the electron transport chain, participates in aerobic cellular respiration which generates energy in the form of ATP;

- she optimized her oral hygiene using an electric flosser and electric toothbrush;

- following discussion with her primary care provider, she reinstated hormone replacement therapy that had been discontinued;

- she fasted for a minimum of 12 hours between dinner and breakfast, and for a minimum of three hours between dinner and bedtime; and,

- she exercised for a minimum of 30 minutes, 4-6 days per week.

The results for nine of the 10 patients reported in the paper suggest that memory loss may be reversed, and improvement sustained with this therapeutic program, said Bredesen. “This is the first successful demonstration,” he noted, but he cautioned that the results are anecdotal, and therefore a more extensive, controlled clinical trial is needed.

It is a sign of just how little we really know about the human brain function, that Bredesen, the head of this successful trial can hold a view almost directly opposite to prevailing wisdom. His model of multiple targets and an imbalance in singling in the brain runs contrary to the popular dogma that Alzheimer’s is a disease of toxicity.

The most common belief in scientific circles is that Alzheimer’s is caused by the accumulation of sticky plaques in the brain. Bredesen believes the amyloid beta peptide, the source of the plaques, has a normal function in the brain – as part of a larger set of molecules that promotes signals that cause nerve connections to lapse. Thus the increase in the peptide that occurs in Alzheimer’s disease shifts the memory-making vs. memory-breaking balance in favor of memory loss.

The downside to this program is its complexity. It is not easy to follow, with the burden falling on the patients and caregivers, and none of the patients were able to stick to the entire protocol.

The significant diet and lifestyle changes, and multiple pills required each day, were the two most common complaints. The good news, though, said Bredesen, are the side effects: “It is noteworthy that the major side effect of this therapeutic system is improved health and an optimal body mass index, a stark contrast to the side effects of many drugs.”

It’s also noteworthy that the main parts of the programme seem to consist of good diet and good dental hygiene, maintaining a lean body weight, significant exercise and lowering stress.

We’ve all heard this before – why is it so difficult for us to follow through?

Orlando

From the Scientific American:

America has experienced yet another mass shooting. This time at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida. It is the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history.![]()

#1: MORE GUNS DON’T MAKE YOU SAFER

A study conducted on mass shootings indicated that this phenomenon is not limited to the United States.

Mass shootings also took place in 25 other wealthy nations between 1983 and 2013, but the number of mass shootings in the United States far surpasses that of any other country included in the study during the same period of time.

The US had 78 mass shootings during that 30-year period.

The highest number of mass shootings experienced outside the United States was in Germany – where seven shootings occurred.

In the other 24 industrialized countries taken together, 41 mass shootings took place.

In other words, the US had nearly double the number of mass shootings than all other 24 countries combined in the same 30-year period.

Another significant finding is that mass shootings and gun ownership rates are highly correlated. The higher the gun ownership rate, the more a country is susceptible to experiencing mass shooting incidents. This association remains high even when the number of incidents from the United States is withdrawn from the analysis.

Similar results have been found by the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, which states that countries with higher levels of firearm ownership also have higher firearm homicide rates.

The study also shows a strong correlation between mass shooting casualties and overall death by firearms rates. However, in this last analysis, the relation seems to be mainly driven by the very high number of deaths by firearms in the United States. The relation disappears when the United States is withdrawn from the analysis.

#2: SHOOTINGS ARE MORE FREQUENT

A recent study published by the Harvard Injury Control Research Center shows that the frequency of mass shooting is increasing over time. The researchers measured the increase by calculating the time between the occurrence of mass shootings. According to the research, the days separating mass shooting occurrence went from on average 200 days during the period of 1983 to 2011 to 64 days since 2011.

What is most alarming with mass shootings is the fact that this increasing trend is moving in the opposite direction of overall intentional homicide rates in the US, which decreased by almost 50% since 1993 and in Europe where intentional homicides decreased by 40% between 2003 and 2013.

#3: RESTRICTING SALES WORKS

Due to the Second Amendment, the United States has permissive gun licensing laws. This is in contrast to most developed countries, which have restrictive laws.

According to a seminal work by criminologists George Newton and Franklin Zimring, permissive gun licensing laws refer to a system in which all but specially prohibited groups of persons can purchase a firearm. In such a system, an individual does not have to justify purchasing a weapon; rather, the licensing authority has the burden of proof to deny gun acquisition.

By contrast, restrictive gun licensing laws refer to a system in which individuals who want to purchase firearms must demonstrate to a licensing authority that they have valid reasons to get a gun – like using it on a shooting range or going hunting – and that they demonstrate “good character.”

The type of gun law adopted has important impacts. Countries with more restrictive gun licensing laws show fewer deaths by firearms and a lower gun ownership rate.

#4: HISTORICAL COMPARISONS MAY BE FLAWED

Beginning in 2008, the FBI used a narrow definition of mass shootings. They limited mass shootings to incidents where an individual – or in rare circumstances, more than one – “kills four or more people in a single incident (not including the shooter), typically in a single location.”

In 2013, the FBI changed its definition, moving away from “mass shootings” toward identifying an “active shooter” as “an individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a confined and populated area.” This change means the agency now includes incidents in which fewer than four people die, but in which several are injured, like this 2014 shooting in New Orleans.

This change in definition impacted directly the number of cases included in studies and affected the comparability of studies conducted before and after 2013.

Even more troubling, some researchers on mass shooting, like Northeastern University criminologist James Alan Fox, have incorporated in their studies several types of multiple homicides that cannot be defined as mass shooting: for instance, familicide (a form of domestic violence) and gang murders.

In the case of familicide, victims are exclusively family members and not random bystanders.

Gang murders are usually crime for profit or a punishment for rival gangs or a member of the gang who is an informer. Such homicides don’t belong in the analysis of mass shootings.

#5: NOT ALL MASS SHOOTINGS ARE TERRORISM

Journalists sometimes describe mass shooting as a form of domestic terrorism. This connection may be misleading.

There is no doubt that mass shootings are “terrifying” and “terrorize” the community where they have happened. However, not all active shooters involved in mass shooting have a political message or cause.

For example, the church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina in June 2015 was a hate crime but was not judged by the federal government to be a terrorist act.

The majority of active shooters are linked to mental health issues, bullying and disgruntled employees. Active shooters may be motivated by a variety of personal or political motivations, usually not aimed at weakening government legitimacy. Frequent motivations are revenge or a quest for power.

#6: BACKGROUND CHECKS WORK

In most restrictive background checks performed in developed countries, citizens are required to train for gun handling, obtain a license for hunting or provide proof of membership to a shooting range.

Individuals must prove that they do not belong to any “prohibited group,” such as the mentally ill, criminals, children or those at high risk of committing violent crime, such as individuals with a police record of threatening the life of another.

Here’s the bottom line. With these provisions, most US active shooters would have been denied the purchase of a firearm.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read theoriginal article.

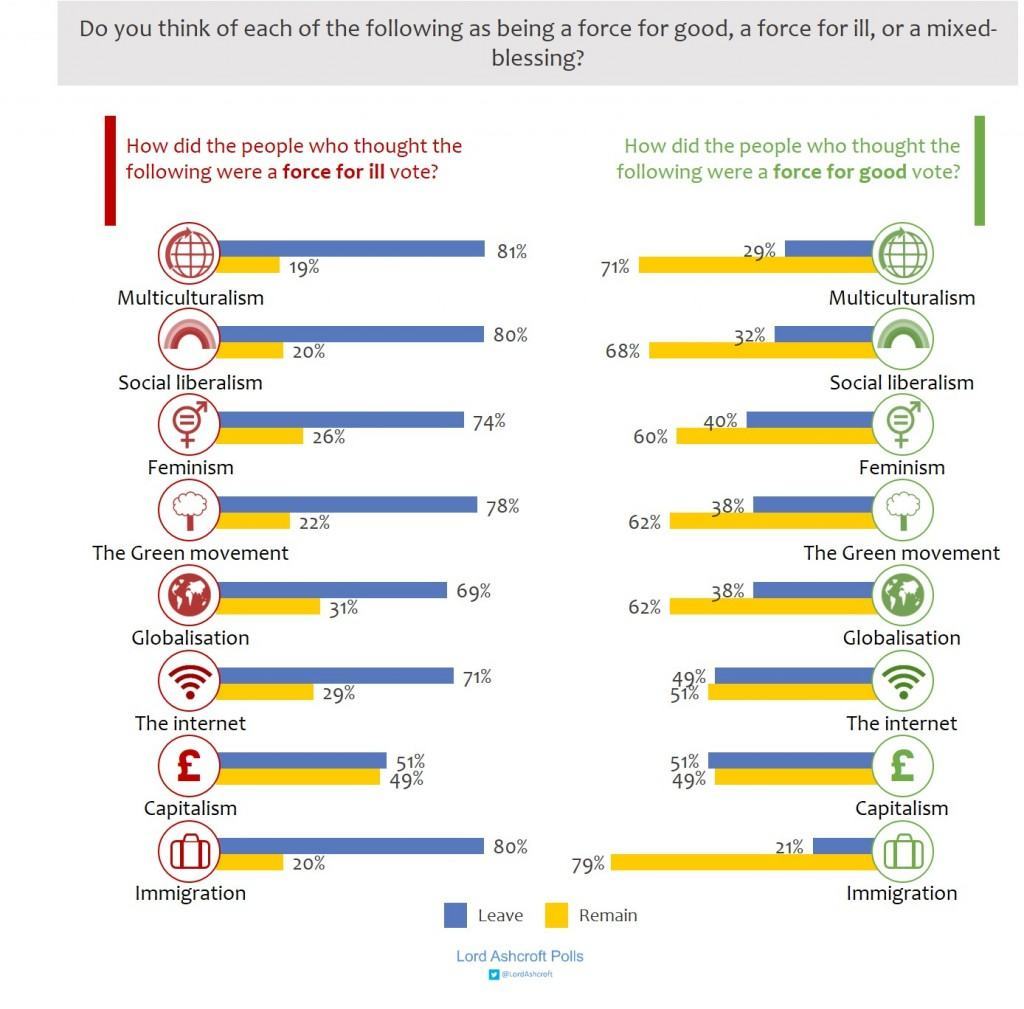

“IMMIGRATION, immigration, immigration,” shouted a headline in the Sun, a right-wing tabloid newspaper, the week that Britain voted to leave the European Union. It followed weeks of campaigning from the Leave side assuring voters that they would “take back control” and restrict EU migration if Britain left the club. Now that the referendum has just been won in favour of Brexit, what will happen to the EU migrants currently in Britain—and to British nationals living in the EU?

Some 3m EU nationals live in Britain, compared with 1.2m Britons who live on the continent. The volume of EU migrants coming to Britain has increased since the club was expanded in 2004. Last year net migration from the EU was at a historic high, mostly because fewer Brits were moving abroad. Many consider this a boon: according to research from the Centre for Economic Performance, a think-tank, EU migrants are more likely to be university-educated, less likely to claim benefits and more likely to be in a job than the native-born population.

The fate of both groups depends on the deal Britain strikes with the EU. Nothing will happen until (or, indeed, if) Article 50, which formally triggers the process of leaving the Union, is invoked by the British government. If the deal includes free movement of people, as in Norway, both sets of migrants would be left broadly as before. If not, the situation is far more complicated. According to Steve Peers, a law professor at the University of Essex, under EU law British citizens who have been resident in another EU country for five years or longer will be able to apply for long-term resident status, but this often means that the migrant has to learn the language. Moreover, older British migrants will probably no longer enjoy the protection to their pensions that comes with being part of the single market—pensions may be frozen rather than pegged to inflation.

Although it may come as a surprise to many who watched the campaign, the Leave side stated before the referendum that EU citizens who were “lawfully resident” in the UK would “automatically be granted indefinite leave to remain”.

According to Sarah O’Connor at the Financial Times, 71% of EU migrants have been living in Britain for more than five years, which makes them eligible for permanent residence under existing laws.

Depending on the deal Britain extracts from the EU, it is more likely that future migrants would be subject to tougher laws, or that family members of current EU migrants would not be allowed in to Britain. Yet although many EU migrants may be able to stay, some may decide not to. On June 27th David Cameron, the outgoing prime minister, condemned the daubing of graffiti on a Polish community centre in London and the verbal abuse of people from ethnic minorities.

Even without new rules, Britain is already becoming a less welcoming place.

Mortal

In the past few years, there has been something of a panic amongst politicians and the relating to the risks involved in being admitted to hospital at weekends.

Although higher neonatal mortality has been reported for babies born at weekends than for those born during the week in the USA, the UK and Australia since the 1970s, the first investigation of a weekend effect in other areas of hospital care was not reported until 2001.

In England, in 2010, Aylin and colleagues showed that the odds of death for emergency admissions were 10% higher at weekends than during the week and, in 2012, Freemantle and colleagues reported that mortality for all admissions (emergency and elective) was 11% higher on Saturdays and 16% higher on Sundays than on other days during the week.

Widespread interest in England about the possible dangers of being admitted to hospital at weekends has prompted several studies into why this might be, three of which have been published this week.

In The Lancet, Cassie Aldridge and colleagues provide initial results from an ambitious cross-sectional study evaluating the effect offered by the roll-out of 7 day services in acute hospitals in England. With a focus on the effect of medical specialist (consultant) staffing levels, the investigators surveyed more than 15 000 specialists in 115 acute hospital trusts to obtain data for the time they each spent caring for emergency admissions on a Wednesday and on a Sunday.

The estimated weekend effect showed a 10% increase in mortality for weekend admissions. Patients received only half as much specialist attention at weekends as on weekdays yet there was no significant association between intensity of specialist staffing and mortality.

In view of the response rate to the staff survey (45%), the limitations of basing adjusted mortality on hospital administrative data (which do not provide any indication of how sick patients are on admission), and the fact that the study did not consider availability of other staff (eg, junior doctors, nurses), the implications of these results should be interpreted with caution.

Although Aldridge and colleagues’ findings challenge one of the most widely held views of the cause of higher weekend mortality, establishing whether increasing specialist staffing levels is a beneficial approach must await their secular analyses over the next few years.

Meanwhile, also in The Lancet, Benjamin Bray and colleagues’ interest is in the level of compliance with evidence-based clinical guidelines.

With a focus on stroke care, the investigators overcome some of the limitations of administrative data by using a specialist clinical database that allows them to adjust mortality for differences in the severity of admissions on weekdays and at weekends. Whereas a study of stroke admissions based on administrative data in 2009–10 reported a 26% higher mortality for weekend admissions than for weekday admissions, Bray and colleagues’ study finds no difference in 30 day mortality in 2013–14; this might reflect an improvement in weekend care or could be due to insufficient casemix adjustment in the earlier study.

Instead of worrying about weekends, the investigators suggest we should be more concerned about patients admitted at night, in whom mortality was 10% higher than in those admitted during the day. As for adherence to clinical guidelines, such as door-to-needle time and a timely brain scan, patients admitted at night were less likely to receive eight of 12 recommended interventions, which, they suggest, might contribute to heightened mortality.

However, before drawing conclusions about the association between adherence to guidelines and outcomes, Bray and colleagues note that although patients admitted at the weekend were also less likely than weekend admissions to receive good quality care, this was not associated with higher mortality.

In a third approach to investigating the cause of increased weekend mortality, Meacock and colleagues looked beyond the hospital to see the effect of primary care.

To do this, the investigators compared the two routes of emergency admissions: direct referrals (mostly from general practitioners) and patients admitted from accident and emergency departments. Whereas the daily number of admissions via accident and emergency departments at weekends was similar to that on weekdays, the number of direct admissions was 61% lower.

While mortality for admissions via accident and emergency was only 5% higher at weekends, for direct admissions it was 21% higher.

Given that, apart from initial treatment in accident and emergency, both sets of patients receive the same inpatient care, this finding provides circumstantial evidence that mortality differences are more likely to be attributable to how sick patients are on admission, rather than the quality of hospital care.

In view of these new, albeit inconsistent, insights into the possible dangers of weekend admissions, what conclusions can be drawn and what further research is needed?

First, caution should be taken in estimating the effect on mortality.

Previous studies based on routine administrative data did their best to use inventive and sophisticated methods to take casemix difference between weekends and weekdays into account, but had little information about how sick patients were on admission.

Studies using specialist clinical databases for specific diseases or clinical departments, which include clinical and physiological data, have found little or no significant difference by day of admission.

Although more such studies are needed to identify which patients might be at risk of weekend admission, what is really needed is a study in which accurate measures of severity are available on all admissions, so that meaningful comparisons of weekends and weekdays for the whole hospital can be made. The increasingly wide use of electronic national early warning scores provides a means of doing that.

Second, even if higher mortality at weekends is accounted for by patients being sicker than during the week, there is a widely held view plus anecdotal evidence that the quality of care is poorer at weekends.

The reason this might not be manifest when investigators consider mortality is because death is not a particularly sensitive measure of quality given that only about 4% deaths are thought to be avoidable whenever admitted.

Attention should therefore be turned to other measures, such as health outcomes (morbidity, quality of life), safety (falls, hospital-acquired infections), aspects of patients’ experience (delays in diagnosis, not receiving sufficient information), operational efficiency (extended lengths of stay, delayed discharges), and educational quality (training of junior doctors at weekends).

Third, perhaps the wrong determinants of poor outcome are being investigated. Maybe nurse staffing levels or the availability of diagnostic staff should be assessed rather than medical staffing.Or perhaps combinations of different professions.

But even that approach might not be sufficient because research on inputs, such as staffing levels, risks missing the processes of care, known to be the key determinants of poor quality care.

For example, avoidable deaths in hospital happen when a patient’s deterioration remains undetected, when staff fail to communicate well with one another, and when the underlying culture of the organisation does not encourage and reward attitudes and behaviours that enhance quality. The importance of such organisational aspects was recognised in 2013 by National Health Service (NHS) England when they recommended ten national clinical standards for emergency admissions, including factors such as access to diagnostics and timely consultant review.

Despite many claims about the quality of care at weekends and strong beliefs about the reasons for this, we need to remain open to the true extent and nature of any such deficit and to the possible causes. Jumping to policy conclusions without a clear diagnosis of the problem should be avoided because the wrong decision might be detrimental to patient confidence, staff morale, and outcomes.

As Bray and colleagues warn, “Because solutions are likely to come at substantial financial and opportunity cost, policy makers, health-care managers, and funders need to ensure that the reasons for temporal variation in quality are properly understood and that resources are targeted appropriately.”

Europe

Here we are, having brought our ball home unwilling to share and play on with our neighbours.

Without a doubt, the chances of the EU failing are now greater than ever and perhaps some Brexiters will celebrate.

There is no doubt that the EU is in desperate need of reform: Schengen doesn’t work, the Eurozone doesn’t work, the situation for the Greeks is dire, Brussels’ public relations and communication are rubbish, many communities have been left behind by the EU, the immediate and longer term humanitarian aspects of the migrant crisis need a coordinated European initiative, and so on.

These are the issues that should have been addressed.

The chances that these issue will be successfully addressed or so much lessened by the absence of the UK from the table.

And that’s 42% of our economy put at risk.

Witch

Every woman born knows that puberty and menopause are inevitable. There is a surprising amount of information around about puberty these days, less so about menopause.

In fact menopause seems to be much more of a non-event. It’s simply the time, two years after your last period that marks the transition. It’s the five or so years beforehand that cause the problem, the perimenopause.

At midlife, women transition from their reproductive years to the natural end of monthly menstrual cycles. This transition — called perimenopause — usually begins in the 40s and ends by the early 50s, although any age from the late 30s to 60 can be normal. It can be difficult to know whether you’ve entered perimenopause, because the hormonal fluctuations begin while menstrual periods are still regular.

Perimenopause can last anywhere from one to 10 years. During this time, the ovaries function erratically and hormonal fluctuations may bring about a range of changes, including hot flashes, night sweats, sleep disturbances, and heavy menstrual bleeding. Other signs of perimenopause can include memory changes, urinary changes, vaginal changes, and shifts in sexual desire and satisfaction.

Some women breeze through the transition.

For many others, the hormonal changes create a range of mild discomforts. And for about 20% of women, the hormones fluctuate wildly and unpredictably, and spiking and falling estrogen and declining progesterone cause one or more years of nausea, migraines, weight gain, sore breasts, severe night sweats, and/or sleep trouble.

For some women, perimenopause can be enormously disruptive both physically and emotionally.

One common menstrual change in early perimenopause is shorter cycles, usually averaging two or three days less than usual but sometimes lasting only two or three weeks. It can feel as though you’re starting a period when the last one has barely ended. In later perimenopause, you may skip a period entirely, only to have it followed by an especially heavy one. Occasionally, menstrual periods will be skipped for several months, then return as regular as clockwork.

The hormonal ups and downs of perimenopause can be the cause of almost any imaginable bleeding pattern. When estrogen is lower, the uterine lining gets thinner, causing the flow to be lighter or to last fewer days. And when estrogen is high in relation to progesterone (sometimes connected with irregular ovulation), bleeding can be heavier and periods may last longer.

Menstrual irregularities are a normal part of this stage. If you and your health care provider decide that efforts should be made to regulate your cycles at this time, be aware that while oral contraceptives are sometimes prescribed for menstrual irregularities, the use of progesterone alone can be a milder intervention.

Progesterone can be used to manage the imbalance of estrogen and progesterone. A clinician can prescribe progesterone or its synthetic cousins, progestins, to be taken the last 14 days of the cycle. This replaces the progesterone that would normally be secreted in an ovulatory cycle and helps to create a more regular bleeding pattern.

There is an especially descriptive phrase “flooding” that just about describes the sudden and unexpected downpouring of menstrual blood that can happen.

About 25% of women have heavy bleeding (sometimes called hypermenorrhea, menorrhagia, or flooding) during perimenopause. Some women’s menstrual flow during perimenopause is so heavy that even supersized tampons or pads cannot contain it. If you are repeatedly bleeding heavily, you may become anemic from blood loss.

During a heavy flow you may feel faint when sitting or standing. This means your blood volume is decreased; try drinking salty liquids such as tomato or V8 juice or soup. Taking an over-the-counter NSAID such as ibuprofen every four to six hours during heavy flow will decrease the period blood loss by 25 to 45 percent.

Don’t ignore heavy or prolonged bleeding — see your health care provider if it persists. Your provider can monitor your blood count and iron levels. Iron pills can replace losses and help avoid or treat anemia.

Other medical treatment may include progesterone therapy or the progestin-releasing Mirena IUD, which is known to reduce menstrual bleeding. If your health care provider suggests hysterectomy as a solution to very heavy bleeding during perimenopause, you may want to try other less invasive approaches first. Removal of the uterus is an irreversible step with many effects.

Heavy bleeding during perimenopause may be due to the estrogen-progesterone imbalance. Also, polyps (small, noncancerous tissue growths that can occur in the lining of the uterus) can increase during perimenopause and can cause bleeding. Fibroid growth during perimenopause can sometimes cause heavy bleeding, especially when the fibroid grows into the uterine cavity.

If very heavy bleeding persists despite treatment, your provider should test for possible causes of abnormal bleeding.

Hot flashes are legendary signs of perimenopause and for some women can continue well into postmenopause, though 20 to 30 percent of women never have them at all. A woman experiencing a hot flash will suddenly feel warm, then very hot and sweaty, and sometimes experience a cold chill afterward.

Many women in both perimenopause and postmenopause experience sleep disturbances. Most commonly, a woman will fall asleep without a problem, then wake up in the early-morning hours and have difficulty getting back to sleep.

As estrogen and progesterone levels decline in late perimenopause and postmenopause, vaginal walls frequently become thinner, drier, and less flexible and more prone to tears and cracks. This can lead to irritation and difficulties with penetration.

In many ways I’m convinced that the whole process just gets so mucked up in order to make the lack of periods a blessing.

Home

There are many wonderful things about going on a summer holiday. The planning beforehand is always key, choosing places to visit, hotels and apartments and trying to balance the needs of very different members of the family. There is that wonderful feeling of heading out that first day, with all of the excitement and expectation of a break, of time together reconnecting. And usually there’s so much to do, moving from place to place, a balance of activities and space to chill.

But almost the best bit, is the feeling of coming home.

The excitement of bening a new place fades. The beds are never quite right, There is never quite the feeling of comfort in a place that isn’t yours. The excitement stops being exciting and starts to be tiring instead.

And then you come home. The cats are waiting. Not all of the plants in the garden have died. Suddenly life is sweeter.

Youth

As I write, my oldest girl is heading out of the house in search of Pokemon.

For the first time, this year’s holiday came with wall-to-wall wifi in both hotels and apartments. Since my provider gave me a good deal on data etc, we didn’t even have to restrict ourselves to the places we were staying. We had data roaming switched on and used it almost everywhere to find recommended restaurants and sites to visit (thank you on-line TripAdvisor). This was probably our first tech-enabled holiday, but…

Pokemon Go was not released in Spain along with the UK. Every time she logged on to chat with her friends (apparently you don’t leave anyone behind on holiday any more) she was confronted with chat about some Pokemon they had collected or hatched, some gym they were plotting to take over.

So as soon as we were home, in the airport we landed at, she was logged in and looking for mythical, ether based life forms. She has woken up and been out of the house before 8am, unheard of in the life of a teenager in the Summer holiday. She has come back home bouncing with energy after completing the 5km walks to hatch something that can only be described as a pony with it’s butt on fire. Why?

This seems to be a craze she’s sharing with all of her girlfriends, and to a lesser extent her younger sister (a little more attached to her bed it seems) but apart from the grief on our holiday, it seems to be only a good thing. At least while it lasts.

Predator

The problem with three young cats is mainly to do with their enthusiasm. They do what cats are clearly meant to do, eat, sleep, hunt and then sleep some more.

The trip to Spain was punctuated by whatsapp messages. “Mouse” would arrive mid-morning Monday. Maybe it would be “Frog” on Tuesday or “Bird”. Almost every other day there would be some poor dead creature listed, or more ominously “Feathers. Still looking”.

But this morning we had two for one, both very much alive, a frog sitting still and keeping herself alive by being boring and a tiny mouse cowering underneath the curtains.

Both had to be caught in a glass and transferred elsewhere. Turns out the trick with a frog is to lower the glass head first so that if it jumps, it jumps into the glass and not your face. With a mouse you need a second person to guard the cats while you approach the mouse.

You can’t just lock the cats out of the room in case you have a runner mouse. If it runs, you want a cat to catch the thing rather than have it live en-suite underneath the floorboards. Having three cats stare it down makes the mouse ignore the huge galumpy human approaching with glass in hand until suddenly it’s stuck in the glass.Well, most of it. The tails can be a bit tricky but worrying too much about the tail can give Mr Mouse a escape opportunity.

Either way, both a frog and a mouse have been safely relocated alive and well.

Back to sleep.

-

August

Precipice

I have voted labour all of my life. Brought up in a mining town, living through the destruction of entire communities, I can’t imagine ever voting Tory. But I honestly don’t think I can bringt myself to vote for Labour under Jeremy Corbyn.

Owen Jones has written an article that articulates far better than I ever could, the questions that need to be answered, the questions that Jeremy Corbyn will fail to answer.

-

How can the disastrous polling be turned around?

Labour’s current polling is dreadful. No party has ever won an election with such poor polling, or even come close. Historically any party with such terrible polling goes on to suffer a bad defeat.

According to ICM in mid-July, “on the team better able to manage the economy,” 53% of Britons opted for Theresa May and Philip Hammond, while just 15% opted for Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell.

Labour’s polling has deteriorated badly ever since Brexit and the botched coup. But it was always bad and far below what a party with aspirations for power should expect.

Corbyn started his leadership with a net negative rating. (Ed Miliband — who went on to lose — started with a net 19% positive approval rating); it has since slumped to minus 41%. At this stage in the electoral cycle, Ed Miliband’s Labour had a clear lead over the Tories — and then went on to lose. But Labour have barely ever had a lead over the Tories since the last general election.

Numerous polls show that most Labour supporters are dissatisfied with his leadership, even if they show little faith in any alternative. One poll showed that one in three Labour voters think Theresa May would make a better Prime Minister than their own party leader and — most heartbreakingly of all — 18 to 24 year olds preferred May.

The response to this normally involves citing the size of rallies and the surge in Labour’s membership. There is no question that Jeremy Corbyn has inspired and enthused hundreds of thousands of people all over Britain. But Michael Foot attracted huge rallies across the country in the build-up to Labour’s 1983 general election disaster.

The enthusiasm of a minority is not evidence that the polls are wrong. There are 65 million people in Britain. If a total of 300,000 turn up to supportive rallies, that means, 99.5% of the population have not done so.

Yes, it’s true that Labour has won all its by-elections since Jeremy Corbyn became leader, and increased majorities. But in his first year, the picture was the same with Ed Miliband. Neither did Corbyn do as badly in the local elections as was predicted. But Labour still lost seats — unprecedented for an the main opposition party for decades — and as Jeremy Corbyn said at the time: “the results were mixed. We are not yet doing enough to win in 2020.”

So the question is: how is this polling to be turned around? There is no precedent for a turnaround for such negative figures, so it needs a dramatic strategy. What is it? How will the weaknesses that existed before the coup be addressed, and how will confidence be built in him and his leadership?

2. Where is the clear vision?

Labour under Ed Miliband jumped around from vision to vision. The ‘squeezed middle’, ‘One Nation Labour’, ‘the British promise’, ‘predistribution’ (catchy). All of them were abstract. There was a lack of message discipline. Random policies were thrown into the ether but nothing brought them together with a clear overall vision.

On the other hand, it was very easy to sum up the Cameron and Osborne’s Tories’ vision. Clearing up Labour’s mess. Long-term economic plan. Balancing the nation’s books.

Reforming welfare. Taking the low-paid out of tax. Reducing immigration. Giving freedom to schools. All sentiments and slogans repeated ad infinitum. Labour canvassers would literally find voters repeating Tory attack lines back at them almost word for word on the doorstep.

What’s Labour’s current vision succinctly summed up? Is it “anti-austerity”? That’s too abstract for most people. During the leaders’ debates at the last general election, the most googled phrase in Britain was ‘what is austerity?’ — after five years of it. ‘Anti-austerity’ just defines you by what you are against.

What’s the positive Labour vision, that can be understood clearly on a doorstep, that will resonate with people who aren’t particularly political?

When Jeremy Corbyn was asked what Labour’s vision under his leadership is, here was his response:

“An economy that doesn’t cut public expenditure as a principle, that instead is prepared to invest and participate in the widest economy in order to give opportunities and decency for everyone. A welfare system that doesn’t punish those with disabilities but instead supports people with disabilities. A health service that is there for all, for all time, without any charges and without any privatisation within that NHS. And a foreign policy that’s based on human rights, the promotion of democracy around the world.”

Will this is vision resonate with the majority of people? Compare and contrast to the Tories’ messaging: constant, consistent, repetitive.

Where is a clear vision for Labour that will resonate beyond those who, on social media and in rallies, show their enthusiasm for Corbyn now?

3. How are the policies significantly different from the last general election?

The Labour leadership effectively has the same fiscal rule as Ed Balls et al in the last election: balance the nation’s books, not to borrow for day-to-day spending, but do borrow in order to invest. The leadership proposes a British investment bank: again, in the last manifesto. The key policy at the launch of Corbyn’s leadership campaign were equal pay audits. That was also in the last manifesto.

The Labour leadership now says it’s anti-austerity: Corbyn has said that they weren’t pledging cuts, unlike Ed Balls. But their fiscal rule is effectively the same, including a focus on deficit reduction “Deficit denial is a non-starter for anyone to have economic credibility with the electorate,” wrote John McDonnell.

Labour would renationalise the railways, he says: but this, again, beefs up Labour’s pledge under Miliband’s leadership. Labour would reverse NHS privatisation: again, Labour at the last election committed to repealing the Health and Social Care Act and regretted the extent of NHS private sector involvement under New Labour. Corbyn opposed the Iraq war: so did Miliband. The Labour leadership’s policy was to vote against the bombing of Syria, as it was under Miliband.

Owen Jones is someone who campaigned for Corbyn. He’s a left-wing journalist. But remains genuinely unclear on the policies being offered. It seems as though Ed Miliband presented his policies as less left-wing than they actually were, and now the current leadership presents them as more left-wing than they actually are.

It’s presentation, style and sentiment that seem to differ most.

These policies have been rejected once. The danger is similar policies are being offered by a leadership regarded as less competent, more “extreme” and less popular.

It’s less than a year in to Corbyn’s already embattled leadership: perhaps there hasn’t been the time to develop clear new policies but surely there needs to be a clear idea of what sort of policies will be offered, not least given what is at stake?

4. What’s the media strategy?

The mainstream media are always going to demonise a left-wing leader. But the public are not simple minded robots who can be programmed what to think, then we might as well all give up.

Sadiq Khan was not standing on a radical left programme in his London Mayoral bid. Nonetheless he was remorselessly portrayed as the puppet of extremists by his opponent and the capital’s only mass newspaper, as well as several national newspapers. He managed to counteract it, and won. His ratings are extremely favourable. The press lost.

Yet for the labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn there doesn’t seem to be any clear media strategy.

John McDonnell has actually made regular appearances at critical moments, and proved a solid performer. But Corbyn often seems entirely missing in action, particularly at critical moments: Theresa May becoming the new Prime Minister, the appointment of Boris Johnson as Foreign Secretary, the collapse of the Government’s economic strategy, the abolition of the Department of Energy and Climate Change, soaring hate crimes after Brexit, and so on.

Where have been the key media interventions here?

When Theresa May became Prime Minister, Labour’s initial response (via a press release from a Shadow Cabinet member) was to call for a snap general election, which (to be generous) seems politically suicidal. As Andrew Grice in the Independent points out, press releases are often sent out so late that they become useless.

Many of Corbyn’s key supporters will not recognise this picture, because they follow his social media accounts. The polling last year showed a huge gap between Corbyn supporters and the rest of the public when it comes to getting news off social media but social media is no substitute — at all — for a coherent media strategy.

Only a relatively tiny proportion of the population use Twitter, for example, to talk about or access political news: disproportionately those who are already signed up believers. Take Facebook. At the last general election the Tories used targeted Facebook ads very effectively.

The Tories paid money to work out who they need to target, and with clear messages tailored for specific audiences, repeated ad infinitum. Labour had lots of different messages, didn’t target them at the right people, had a more diffuse audience, and many of the people targeted would only have seen a Labour post once.

You end up with huge engagement amongst people who are already engaged — and you end up repeating messages that get the most engagement, because those are the ones that get your most dedicated supporters most enthused. You energise your core supporters (and end up sticking to the messages that energise them most), but fail to reach out .

The serious point about the Tories’ social media strategy is that it was not a substitute, but just a complement to a wide-ranging overall package. They weren’t relying on social media at the expense of the mainstream media — where their message dominated; they had a clear overall message they repeated over and over and over again.

There are around 65 million people in Britain. Most people do not spend their times discussing politics (or seeking out political content) on social media. That’s just an obvious fact. Millions of people do get their information about what’s going on in politics, say, from watching a bit of the 10 O’Clock News, or listening to news on radio. Radio 2, for example, has 15 million listeners, four million more than voted Conservative at the last general election.

A study in 2013 found that 78% of adults used television for news; just 10% opted for Twitter. Things have not changed dramatically since then (indeed Twitter has been stagnating). The study found that people had poor trust in Twitter as a news source. Most people hear a bit of news about politics on the TV or radio.

An effective media strategy means appearing on TV and radio at every possible opportunity, and lobbying for appearances when they are not offered; reacting swiftly to momentous events like a change in Prime Minister; having message discipline underpinning a coherent vision; planning ahead, so that you are always one step ahead; sending press releases in good time so they can be reported on, and so on.

Such a strategy does not seem to be in place within the current Labour Party.

So what could a coherent media strategy look like? How would it genuinely reach out to the millions of people who aren’t trawling through Facebook for political content with an appealing coherent vision?

5. What’s the strategy to win over the over-44s?

Britain has an ageing population. Not only are older Britons the most likely to turn out to vote, but they are increasingly likely to vote Conservative. At the last general election, the Tories only had a lead among people aged over 44. Labour had a huge lead among 18 to 24 year olds, but only 43% voted; but nearly eight out of ten over the age of 65 voted, and decisively for the Tories. Labour’s poll rating among older Britain is currently catastrophic, particularly the leadership’s own ratings.

Unless Labour can win a higher proportion of older voters, the party will never govern again.

When Jones asked Jeremy Corbyn in a recent interview what his strategy was, he came up with some sensible starting points: respect for older people (this needs fleshing out in policy terms), dealing with pensioner poverty, and social care.

The problem is — that’s the first I’ve heard of it. Where’s the strategy to relentlessly appeal to older Britons who are so critical in deciding elections? There’s no point having a vision unless it is repeated ad infinitum, rather than being offered after being prompted: it will go over everyone’s head.

6. What’s the strategy to win over Scotland?

This was identified as a key priority during Corbyn’s last leadership campaign. It is difficult, currently, to see how Labour can win a general election without winning a considerable number of seats North of the Border. At the last Holyrood elections, Scottish Labour came a disastrous third. Here was the manifestation of problems that long predate Corbyn’s leadership.