We all have our favourites. These are the parts of the British Museum’s main collection that I revisit time after time.

The Lewis chessmen are easy to love.

They are a 12thcentury set of chess players, mostly carved from walrus ivory. They were found in 1831 on the Scottish Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. The hoard contained 93 artifacts of which 82 pieces are owned and usually exhibited by the British Museum in London and the remaining 11 are at the National Museum of Sctoland in Edinburgh.

At the time they were made, this part of the UK was ruled by Norway and the chessmen are probably Norwegian, certainly nordic probably from Trondheim, Norway in origin.

They may have been hidden (or lost) after some mishap occurred during their journey from Norway to wealthy Norse towns on the east coast of Ireland, such as Dublin. The large number of pieces and their lack of wear may suggest that they were the stock of a trader or dealer.

All the pieces are sculptures of human figures, with the exception of the pawns, which are smaller, geometric shapes. The knights are mounted on rather small horses and are shown holding spears and shields.

The rooks are standing soldiers or warders holding shields and swords; four of the rooks are shown as wild-eyed berserkers biting their shields with battle fury.

To modern eyes, the pieces, with their bulging eyes and glum expressions, have a distinct comical character. This is especially true of the single rook with a worried, sideways glance and the berserkers biting their shields, which have been called “irresistibly comic to a modern audience.” But at the time the comic or sad expressions were probably intended to display strength, ferocity or, in the case of the queens who hold their heads with a hand, “contemplation, repose and possibly wisdom.”

To me, the queens always look slightly fed up with the sheenanigans going on around them

The detail of the carving is extraordinary but it is the approachability of the figures rather than their beauty that brings me back to see them each time I visit the museum.

And ofcourse there is also the idea of finding buried treasure to enjoy while wandering around the various hoards in th emuseum.

There is something incredibly exciting, romantic even about the idea of finding a hoard of gold treasure.

There is the excitement of finding a huge amount of gold coins, the astonishing beauty the jewellery, the ferocity of the weapons and the mundane objects and the glimpse into everyday life that they provide.

The delicacy of the links in this decorative chestpiece by “primitive” survivors at the end of the Roman Empire, around 1100 are astonishing.

In the UK we talk about “treasure trove”. Under common law, treasure trove was gold or silver in any form which had once been hidden away and since rediscovered, where no owner could be found.

And over the years, thousenads of people have wandered hopefully over fields and bogs with metal detectors looking to find buried or discarded treasures from history and pre-history.

But often the items found would not be counted as treasure trove in English Law. The famous ceremonial helmut from Sutton Hoo recovered in 1939 was determined not to be treasure trove as it was a ship burial with no intention to recover them later. And objects which were not treasure trove, belonged to the person who found them and could be sold to the highest bidder.

As a result, the law regarding treasure trove was amended in 1996 so that these principles no longer hold. The definition of treasure trove was extended to “treasure” to include items of historical interest etc.

Were the Celts the blingy chavs of pre-history? Looking at the intricate beauty of some of the chains, I’m fairly convinced that I’d be a happier Celt than civilised Roman. It helps that a significant number of the burial finds at the recent Celt Exhibition were for rich and powerful Celtic women.

Close to where I was born, they found the most beautiful ornamental cape made of gold. It is slight, most probably made for a young woman. It could be that she is the beloved wife or daughter of a powerful man, but it is also possible that she was significant in her own right.

It was found by some men quarrying for stone and originally had hundresd of amber beads attached. They mostly went “missing” on the way to the museum. It would probably have had a cloak or fine robe attached to it. Maybe it was worn for religious or ceremonial purposes. It’s made from a single ingot of gold, beaten and worked with great skill and delicacy.

Over the years more and more fragments have been “located” and restored to the cape. The problem with the idea of “treasure” belonging to the Crown rather than the finder, is the tendency for it to never be reported but to disappear until re-sold on the overseas market.

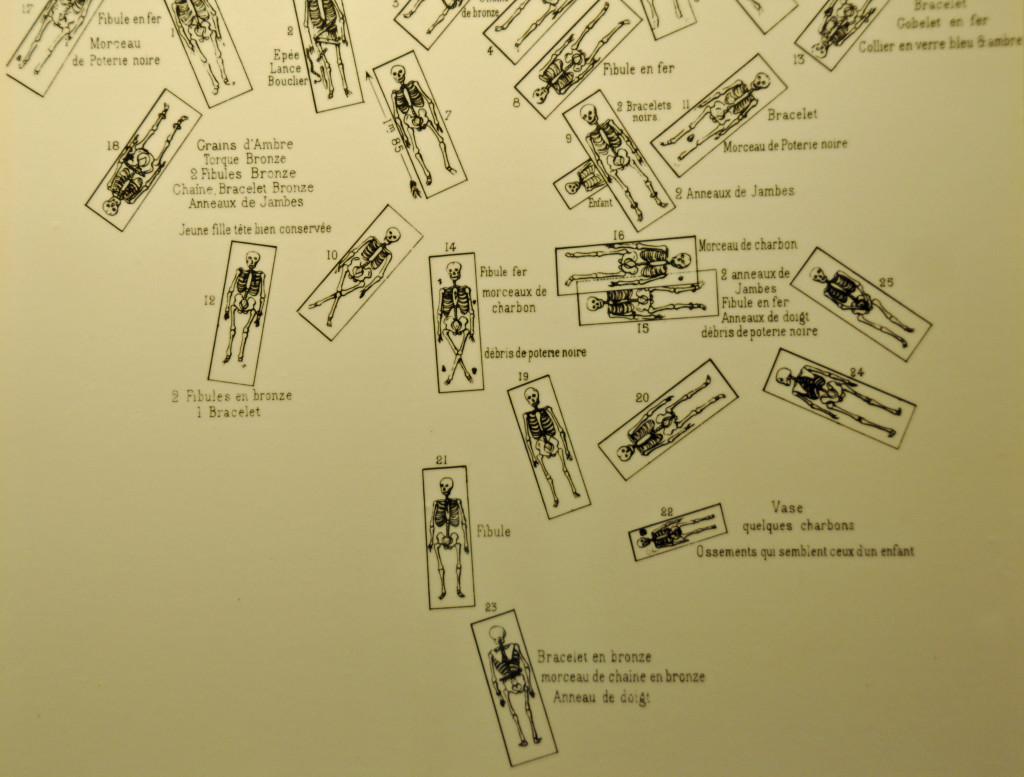

As well as beautiful decorations and bodies. many finds include fierce weaponry, notably shields and swords. And often where one body is found, a number of others are located nearby leading to a variety of hoards and hoard goods.

But as well as the extraordinary, the ordinary everyday objects from this earliest part of history are fascinating. The communal cauldrons for family and smallholdings to sit and celebrate, eating and drinking together. It seems clear that whilst life was hard, there was also a great deal of celebrating.

Above all it is the ability to compare and contrast the exhibitions, many world famous and some very controversial, from around the world that makes a global museum like the British Museum work for visitors.

The Parthenon Marbles (Elgin marbles) are always busy with selfie-taking tourists at the British Museum.

They were created as part of the Temple in Athens dedicated to Athena and built at around 440BC and they are astonishingly beautiful in shape and form. The details of the figures proportions is extraordinary. You could imagine that the fabric carved from stone was soft to touch. It looks as if it might blow in a light breeze.

My favourite piece has always been the Selene Horse which looks out of his plinth as if to grab and apple.

Along one wall there is a procession of horses and riders with a real sense of movement and personality of both horses and men.

Whilst opposite you can see the celebrations of the gods and goddeses of the time relaxing and enjoying life.

Alongside the main gallery are a couple of rooms with related marble friezes from Athens

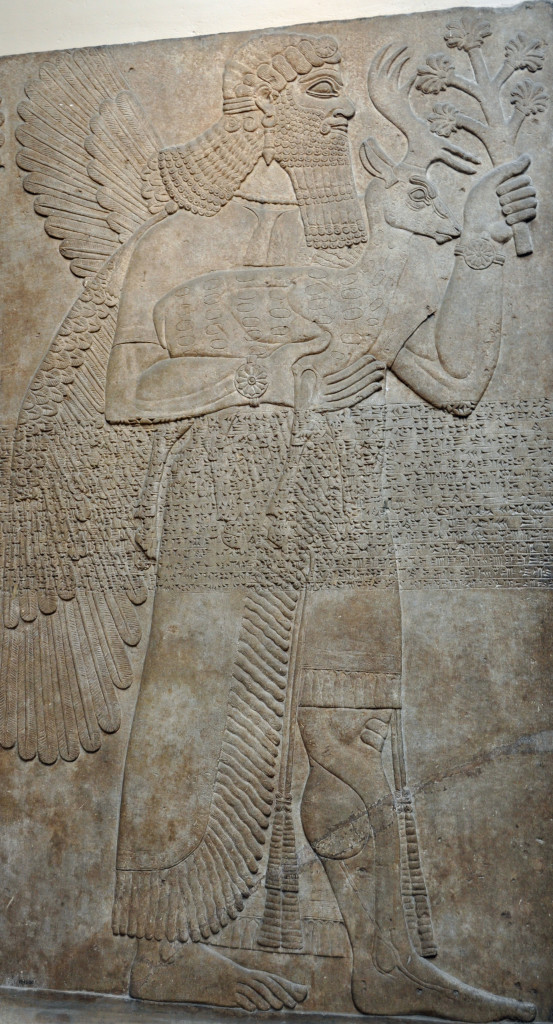

And for me, part of the value to having the marbles in a global museum is to be able to see them in historic context, next door to the friezes from their Assyrian predecessors (from around 645BC to 700BC)

The difference in style between the two cultures is striking.

The Assyrian friezes show much more stylised representations of people. There is considerably less detail on clothing and much more emphasis on beards.

There is clearly a very different mythology present and celebrated. If anything, the bird-headed people are reminiscent of the Ancient Egyptians (one room along) or even the Aztecs in the opposite corner of the museum.

And yet no matter the differences between the various styles, the very differing priorities given towards war, the differences in the lifestyles of their kings and leaders, there is also an overwhelming sense of commonality. It can be found in the artists and craftsmen striving to capture and idealise the world around them and also the small everyday portraits of a life led thousands of years ago.