The British Museum often holds great exhibitions, usually with artifcats from around the world such as terracotta warriors from China or mummified remains from Pompei.

This year they’re holding an exhibition relating to something closer to home: the Celts.

The basic premise seems to be that there is no such thing as Celts, at least not as a single cultural identity. Being Celt, essentially meant that you weren’t Roman. Whilst there are some common linguistic roots that can be identified across Europe, the description Celts is a relatively recent one and in all likelihood would not have been recognised by the various communities around Europe.

What did it mean to be a Celt?

The main impression is one we take directly from the Romans: to be Celtic was to be uncivilised or primitive.

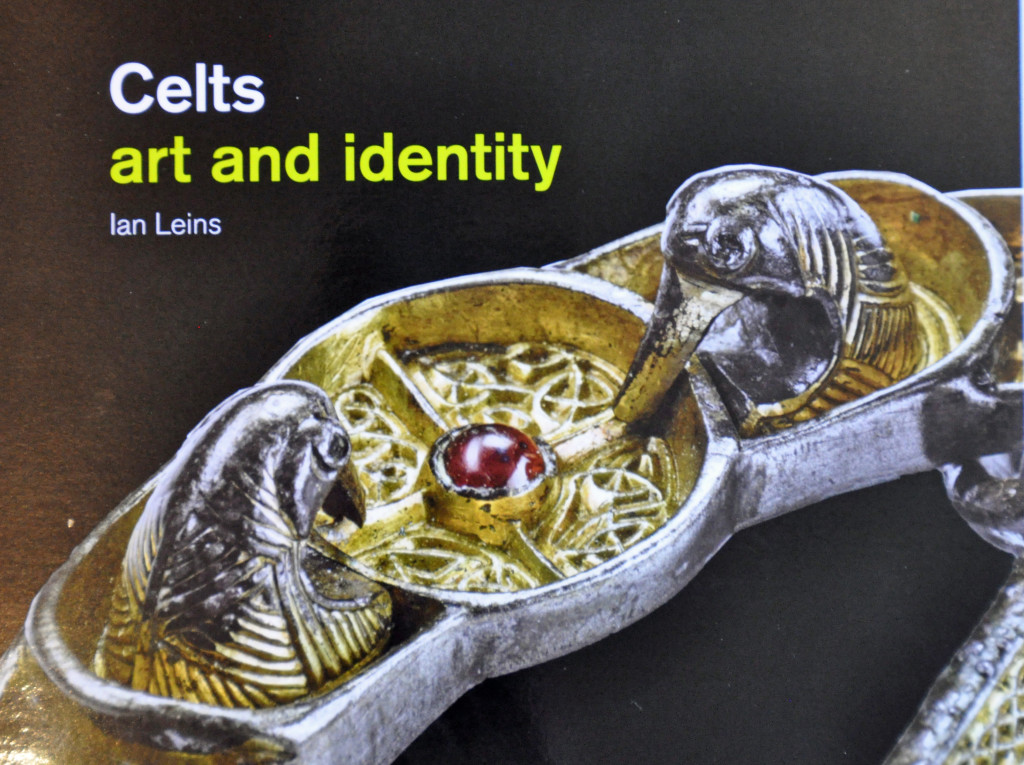

But that didn’t stop the Celts from making the most beautiful jewellery and other goods that were widely traded both across Celtic communities and with Rome itself. The Celt were skilled metal workers, as exemplified by their torcs, metal necklaces worn widely.

They also made beautiful brooches with elaborate pins and clasps.

Much of the information (and exhibition) is derived from burial goods discovered by chance. There is something of the magical about buried treasure, and coins found as part of treasure trove.

Much of the information (and exhibition) is derived from burial goods discovered by chance. There is something of the magical about buried treasure, and coins found as part of treasure trove.

It remains astonishing how modern the art of the Celts appears to us. The stylised horse remains clearly identifiable and pleasing to our eyes.

The exhibition contained a significant number of burial goods attributed to women suggesting that it was possible for Celtic women to hold power and authority (as well as considerable wealth).

But weapons were well represented in the exhibition especially the more robust shields.

There were also some astonishingly beautiful domestic objects such as cauldrons, most probably used for feasts and special occasions.

Some of the bowls and jars were for drinking at feasts, large and small, communal and sharing.

The exhibition also raises the idea that the Celts would offer up precious goods, jewellery, coin, weapons to special, presumably religious sites. Roman commentators describe sites where gold objects were to be easily found yet the locals left them well alone.

It is the detail work that most astounds, whether on a knife, a brooch, or piece of furniture

But whilst the Romans prevailed conquering much of England eventually, the borders were always uneasy with the Scots and the Welsh. And though the Celts were converted to Christianity, the decoration of religious objects such as crosses remained recognisably non-Roman or Celtic.

And even when the object itself has lost it’s purpose such as the plaque below, the decorative detail remains beautiful.

The metalwork decoration on shields, buckles, clasps for brooches or cooking pots is astonishing.

And the detailed artwork in the St Chad Gospels (AD 700-800) shows a clear Celtic influence on the Medieval Period.

But whilst the exhibition’s central premise “no such thing as Celts” is difficult to buy into with such a wealth of treasures on display, the idea that Celtic identify has essentially been reinvented through the years is made simply and clearly.

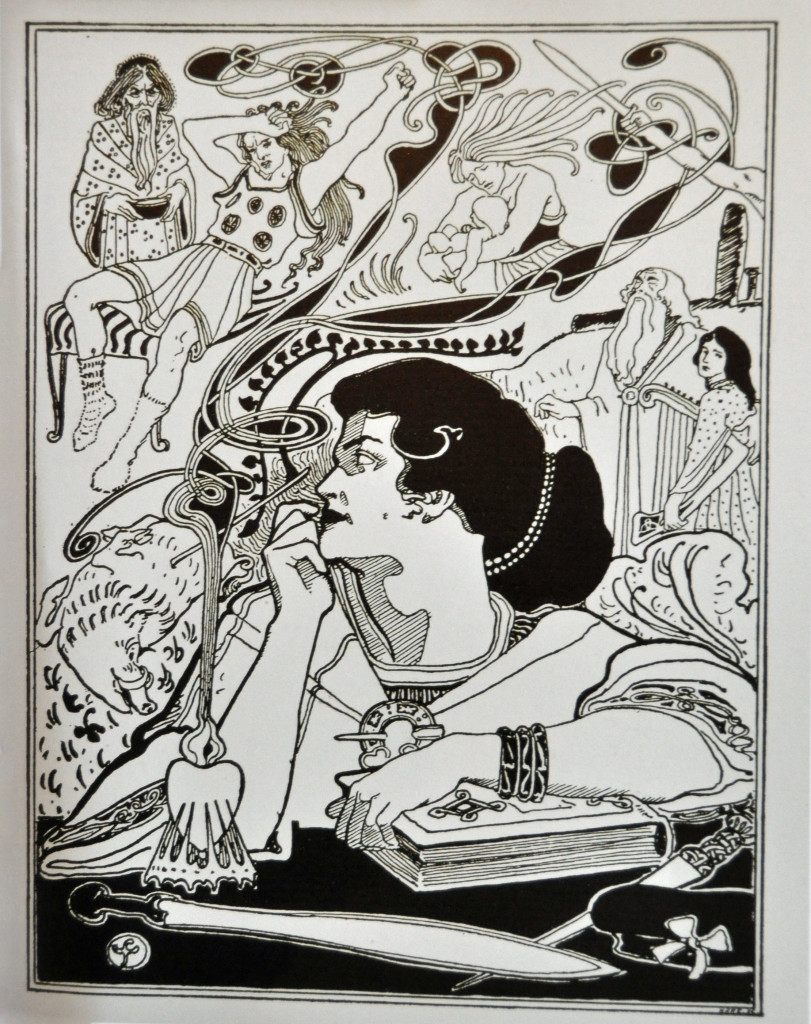

The re-imaging of celts, warriors and druids, as savages from the New World, or elegant SIdhe fey for the late Victorians is very obvious. You can see the idealisation of the pastoral, the “one-with-nature” trope so commonly found in industrial societies. Our fondness for the idea of Celts may just feed into our fondness for the “noble savage” myth, our rose-coloured spectacles that we take out only for our pre-industrial past.

And it is impossible to deny the impact of “Celtic” art upon the art nouveau.

In the final room, the exhibition gives an example of the continuing reimagining of Celts and their mythology with Cuchulain, a new marvel Comics hero, part of the Guardians of the Galaxy trope.