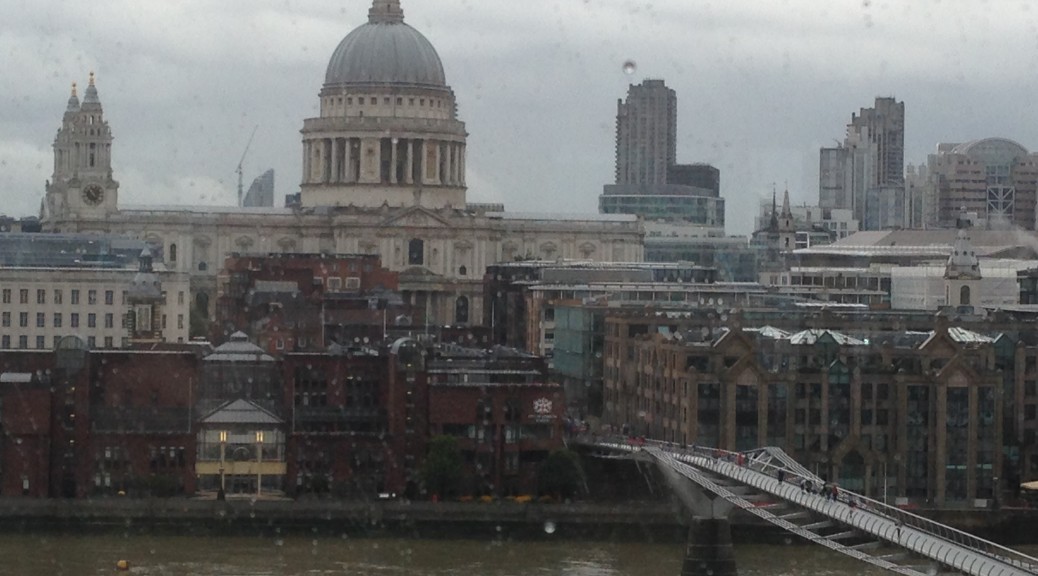

The Royal Academy in London is a wonderful gallery for viewing current as well as historic artists. there’s an exhibition of Chinese artist Ai Weiwei that has just started but like much modern art, it seems that the backstory is quite important in understanding what the art is about.

Ai Weiwei was born into China’s cultural avant-garde, his mother a writer and his father an artist and activist. But after Ai Qing returned to Shanghai from studying painting in Paris in 1932, he was jailed for leftist leanings by the Nationalist government. Unable to paint in prison, by the time he was released three years later he was famed for the poetry he had written behind bars – now considered a pillar of Modern Chinese literature.

His first 20 years were spent in harsh confinement – now at the hands of the Communist government. Ai Weiwei’s father had joined the Communist Party after his release from prison, and become a confidante and poet to Mao Zedong as the People’s Republic of China was founded.

But in 1957, the year Ai Weiwei was born, such literary expressions were deemed threatening and Ai Qing was denounced as a rightist. Banned from writing and exiled first to north eastern China then to the north west, he was forced into hard labour while the family lived in an underground, rat-ridden shed. The family were only allowed to resettle in Beijing 20 years later, when Mao died in 1976.

Today, those roots have branched into a career more expansive, provocative and unapologetic than any of Ai Weiwei’s contemporaries. “He is the most daring and aggressive artist in the stand against official China,” Uli Sigg, a renowned collector of Chinese art, told RA Magazine. “Other Chinese artists are subtle in their subversion, or avoid directly speaking out. In his directness and fearlessness he is set apart.”

He has campaigned for human rights since his student days – his Beijing troupe of artist-activists, The Stars, were getting their exhibitions shut down by police as early as 1979 – but it was in 2008 that he reached a global audience.

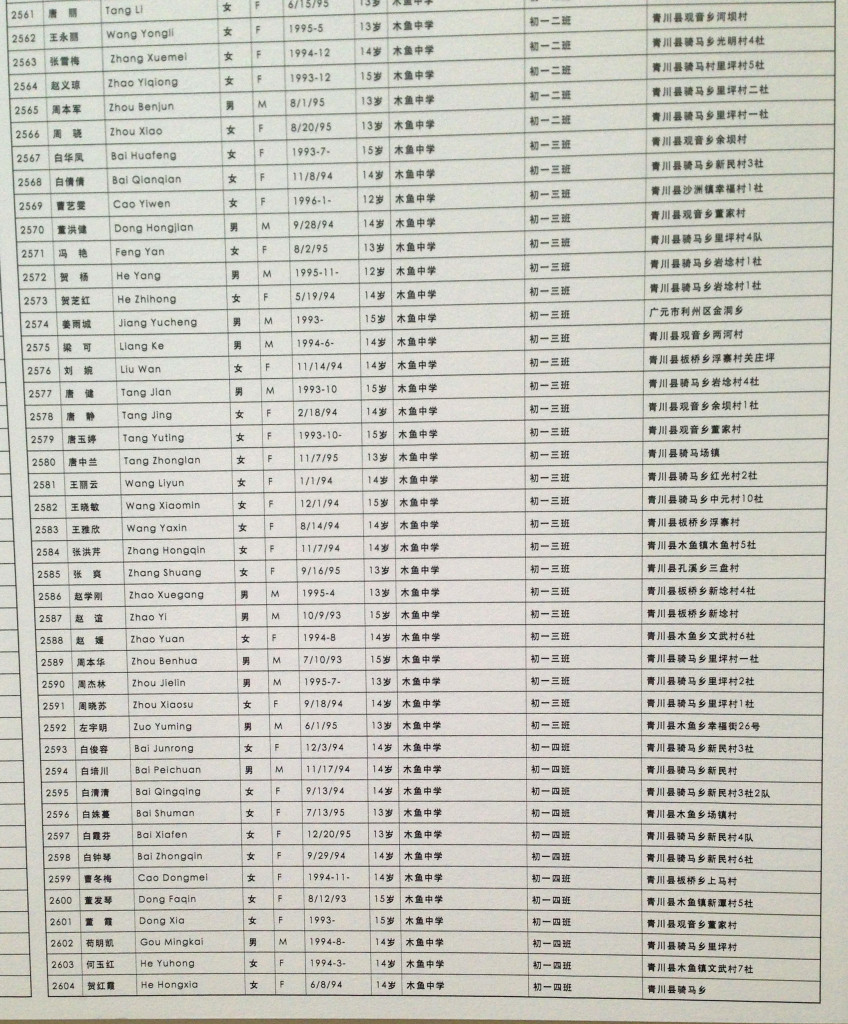

Following Sichuan’s devastating earthquake, the artist attempted to name all the children who were killed due to substandard construction of their schools, while the government remained silent. He eventually published a list of over 5000 online – which saw his volunteers arrested, his blog shut down and a brutal beating for Ai.

Nonetheless, he went on to make Straight, 2008-2012, a 90-tonne assemblage of reinforcing steel bars reclaimed from the site of the collapsed buildings and hammered back straight.

2008 was also the year he collaborated with architects Herzog and de Meuron to design Beijing’s “Birds Nest” Olympic Stadium – but Ai’s disgust at the government’s self-promotional rhetoric and continued disregard for human rights led him to publicly boycott the Games. Read his opinion piece in the Guardian.

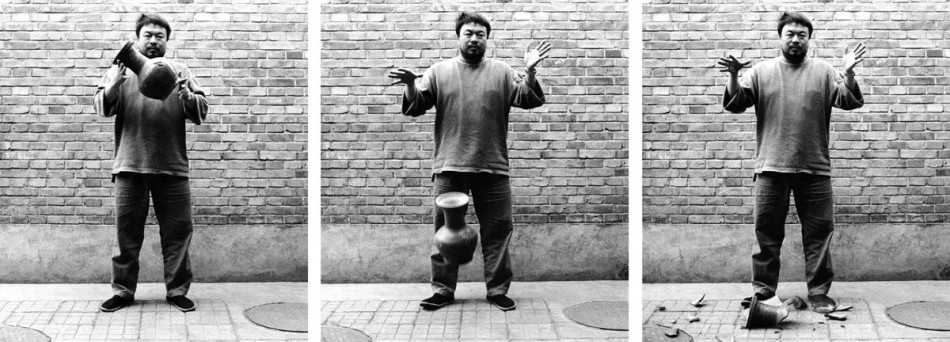

In 1995, Ai Weiwei smashed an antique urn. Or did he? When he came back to Beijing, he became fascinated with the traditional heritage that Mao had tried to wipe out during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). He would visit antique markets, gathering items that could be presented as artworks in themselves, or “readymades” – among them, 2000 year-old urns from the Han Dynasty. Creating what is still one of his most provocative works, the artist photographed himself dropping one.

Was he sacrificing one pot for the greater good, highlighting what’s happening to Chinese heritage every day? Or was he asking us to question what we value? “You believe what you see because he tells you it’s a Han Dynasty urn – but then he also tells you that the fakes in the markets are so good you wouldn’t be able to tell them apart,” our curator points out. “The techniques to make the fake Han Dynasty urn are probably the same as the real ones, so does it even matter?”

Was he sacrificing one pot for the greater good, highlighting what’s happening to Chinese heritage every day? Or was he asking us to question what we value? “You believe what you see because he tells you it’s a Han Dynasty urn – but then he also tells you that the fakes in the markets are so good you wouldn’t be able to tell them apart,” our curator points out. “The techniques to make the fake Han Dynasty urn are probably the same as the real ones, so does it even matter?”

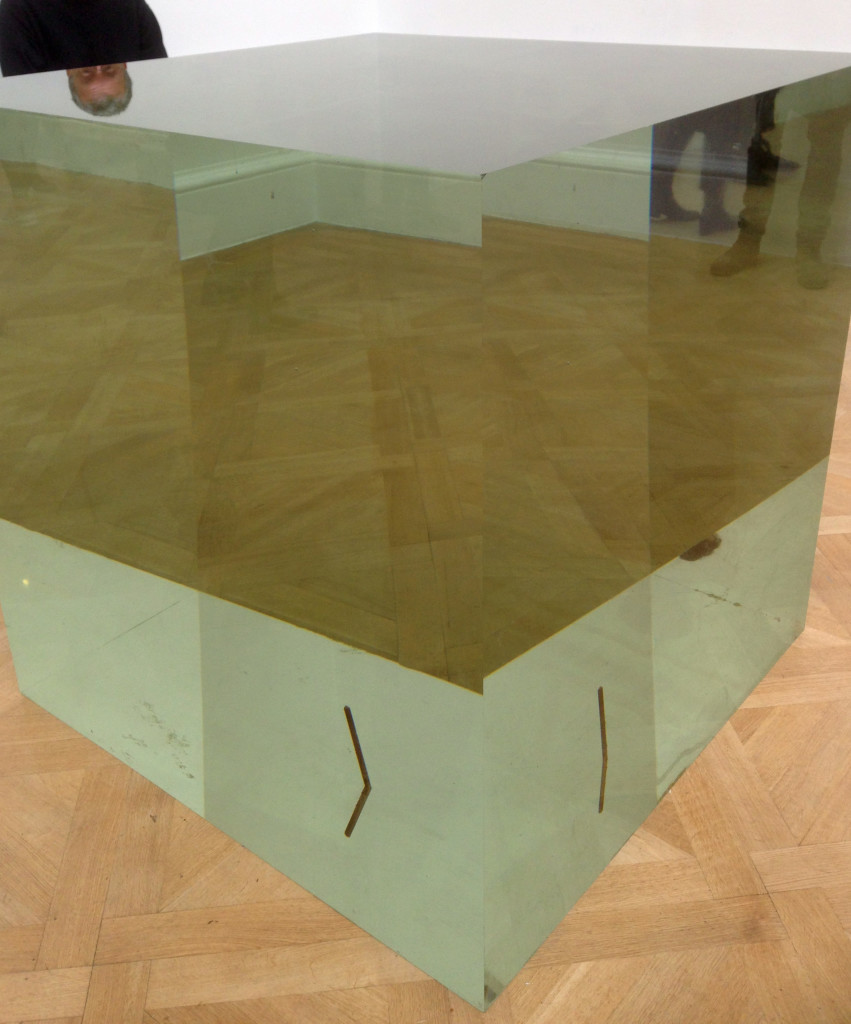

In the RA exhibition, there are a number of works that were once something else (see above Treasure Box, above; based on a piece of expensive, antique furniture). Creating strange and beautiful new forms, he often starts with the antique tables and chairs that, as China has developed into a contemporary global power, have stayed out of fashion replaced by modern often mass-produced objects.

He does the same with materials. Purchasing fragments of dead wood from the mountains of southern China, Ai had them stitched together by skilled carpenters into the eight towering new trees that stand in the RA courtyard.

Watch a timelapse video of the installation of Tree here.

In 2011, Ai Weiwei disappeared for 81 days. He was detained in a secret prison by authorities and eventually released on bail with no explanation. His studio remains under the surveillance, as it has been since 2009, of about 15 cameras dotting his compound. In Surveillance Camera, below, Ai Weiwei sourced marble from an imperial Chinese quarry to craft a perfect, polished surveillance camera (left) – once again, deftly twisting the associations of historically-loaded materials back on themselves.

The artist’s passport was confiscated when he was detained and wasn’t returned until last month – preventing him from leaving the country.

I revisited the Ai Weiwei show at the Royal Academy with a friend. It’s astonishing how different things feel second time around – not sure why.

It is ofcourse all very conceptual, all very political but I still prefer to wander around and view the pieces without a piece of tech telling me what I should be looking at and thinking about. It does rely somewhat on having read up on pieces of work beforehand, maybe in being able to make a second or third visit to enjoy it fully and be able to take time to think it through.

The recurring theme of maps and the Chinese homeland is interesting. I’m not sure it works so well with the ironwood contours as opposed to the porcelain counters but it certainly raises interesting questions about the idea of a patriotic dissident.

And a lot of his work plays with the recycling of materials discarded or trashed as the country embraces the new, the bright and shiny whilst rubbishing the tradinitional crafts and craftsmen that Ai WeiWei makes such god use of in his work.

The room full of reclaimed steel girders alog with the names of the dead victims of shoddy building in an earthquake zone is quite beautiful in the way it flows river-like across the floor. It is surprisingly serene, maybe in the way funerals can be serene

The ceramic work was a little bit harder to get hold of intellectually – not sure about the crabs.

So the destruction of the Han dynasty pot was displayed along with the “trashing” of pots by drip paint or brand painting. It raises the question of what we find important about these artifacts. their age, their appearance, the respect they engender as opposed to the functionality or inherent beauty of the shape etc

A fair amount of the exhibition deals directly with his troubled interactions with the Chinese state including a series of boxes containing dioramas describing his detention which work amazingly well in terms of claustrophobia and offense.

There was also a piece that I’ve recently seen at the RA Summer show which is just such fun with reflections both internally and externally with the people passing by.

But my favourite piece continues to be a chandelier made of bicycle frames which is at once very graphic, very beautiful and strange.