One of my daughters is at university whilst the other will probably leave for university this September. I don’t like to think about the latter. I’m busy pretending to myself that my babies still live at home, whilst also, and in an entirely contradictory manner, congratulating them on growing into such wonderful women. But probably, by the end of the year, we will have two semi-adult, semi-independent children living away from home, and that costs money.

There is a debate at the moment about student fees in the UK. Changes in the way the UK finances tertiary education mean that we now have the most expensive undergraduate courses in the world.

University coasts break down into two component parts: fees for tuition and maintenance.

In England annual university fees are now £9250 a year. The loans are “owned” by a private company and the interest rate charged, which accrues from the minute that you first take out the loan, is around 6% making for a cost of more than £555 a year for the start of your course.

However large the loan is that you build up, let’s say £27,750 capital over three years plus interest accrued £3,465 by the end of a three year course i.e. £31,215, you will only start repaying it when you earn more than £21,000. repayment is charged through the UK payroll system of taxes (PAYE) at a rate of 9% pa. on top of the standard UK income tax rates. This additional tax is paid until either the loan is paid off or 30 years have passed, in which case any outstanding amount is written off.

So it’s an expensive business having children at university. When I consider the rather measly 6 hours contact time my eldest enjoys at university, the cost is only bearable when viewed as compensating or supplementing the 35+hours that her sister will require.

It costs roughly the same amount again for maintenance i.e. accommodation etc so in reality many children will end up with debts of around £60,000.

And since the loans are only repaid over a certain income threshold, and since many women will take a career break to have kids and return to work only part-time, a substantial proportion of the loan balance will never be repaid (around 45% of the total loan portfolio). This unpaid balance is building up, but ultimately will be the responsibility of the government ie. all tax payers, graduates or otherwise to repay.

We decided to pay for our children’s maintenance ourselves, and are obviously lucky enough to afford to do so. But we decided to encourage our daughters to take out a student loan for the fees. A number of friends find this decision incomprehensible with one going so far as to ask how we could do such a thing, having happily paid for our children to attend private schools as if they were one and the same issue.

Hmm.

In the UK we have seen a vast expansion of university places such that the number of children attending university has risen from around 20% to 50% of the population. And that expansion has been funded largely by the rise in student fees. Calls to reduce or remove fees entirely, seem to ignore the consequence of cutting places for students to study. The country could not afford to pay for 50% of kids to attend to university if it was all paid for by central government.

And so you see a rise in the number of people suggesting that it would okay to restrict university places, because university should not be the be-all and end-all. University, apparently, is not right for everyone and we have gone too far in suggesting that it is.

My problem with this argument, is that it seems to be made mostly by people who have no doubt that their children will attend university, come what may. University may not be for everyone else’s kids, but it most definitely is the right place for their kids. other people’s kids can grow up to be plumbers and electricians. Their kids will grow up to be middle-managers, lawyers, doctors etc.

Because when people of my generation went to university, there was an obvious restriction on the number of places at university. And that had consequences. Most of the people I know now, went to very safe, very middle-class schools, private or grammar. Almost everyone they knew as kids went to university, and the idea that they were part of only 20% of the population doesn’t really ring true for them. I went to a very poor working class comprehensive state school. Out of a school year with around 180 pupils, around around 4 of us went to university. So whilst almost 100% of my middle class friends’ classes went to university, just 2% of my peers managed to make it to university.

Any suggestion that we should cut back on university places, inevitably means cutbacks for the working class, for the poorest amongst us.

So my children will take out student loans that will be expensive and unwieldy to pay back, because in part this will fund kids’ education who could not afford to attend university without a loans system.

They will also take out student loans, because at some level, knowing that they personally are paying for their university course, will hopefully encourage them to try and get the best value out of their course. It will give them some skin in the educational game.

Maybe.

I’m told that all young kids want to do is chill out and get pissed, that the loan is somethings they will simply write-off or ignore. It seems to me that some kids will be like this and some won’t. I’m hopeful that my kids have been raised with a greater sense of responsibility but also believe that times have changed and this generation of young people is incredibly more hard-working and focused than our generation ever was.

Either way it has nothing to do with paying private school fees which are absolutely indefensible from a moral societal perspective. People pay for private schools because they believe it will advantage their kids in some way, much as any other selection process within education privileges children. We paid for private education because we wanted both girls to attend single-sex schools, to be within a highly motivated, focused and quite narrow academic stream and obviously because we likes the additional facilities that mad wit easier for the kids to study and study well.

We had the money and were willing to spend it. Other people without the money, make different choices where they can such as sitting for competitive grammar schools etc. There is no moral high ground in terms of selective education.

& it would be stupid to pretend otherwise, I have voted and will continue to vote for a government willing to abolish all types of selective education, whether academic or faith. But whilst it’s available, we made use of the advantage it could offer our daughters.

And the privilege we are willing to offer our kids continues unabated. If my girls want to study for masters or doctorates because they’re enjoying their academic studies that much, then they’ll be able to do so, financed by the bank of mum and dad. If they want to live and work in London, we will help them do so again, financed by the bank of mum and dad.

& at the back of my mind is the knowledge that other people’s children don’t have those choices. The world of work is narrowing; the middle classes are contracting. I want my girls to be happy but, like most parents, I need them to be safe first and foremost.

Because ultimately money is just a tool, a way to afford a life you want to live and we want to live close to our children and for them to be happy (in the hop that th two are not incompatible). Happiness wasn’t a factor in our decision making when we were younger. We had to earn money to live. Now that we have the money, I’d like my daughters to have broader choices, to have a safety net to catch them if those choices don’t work out.

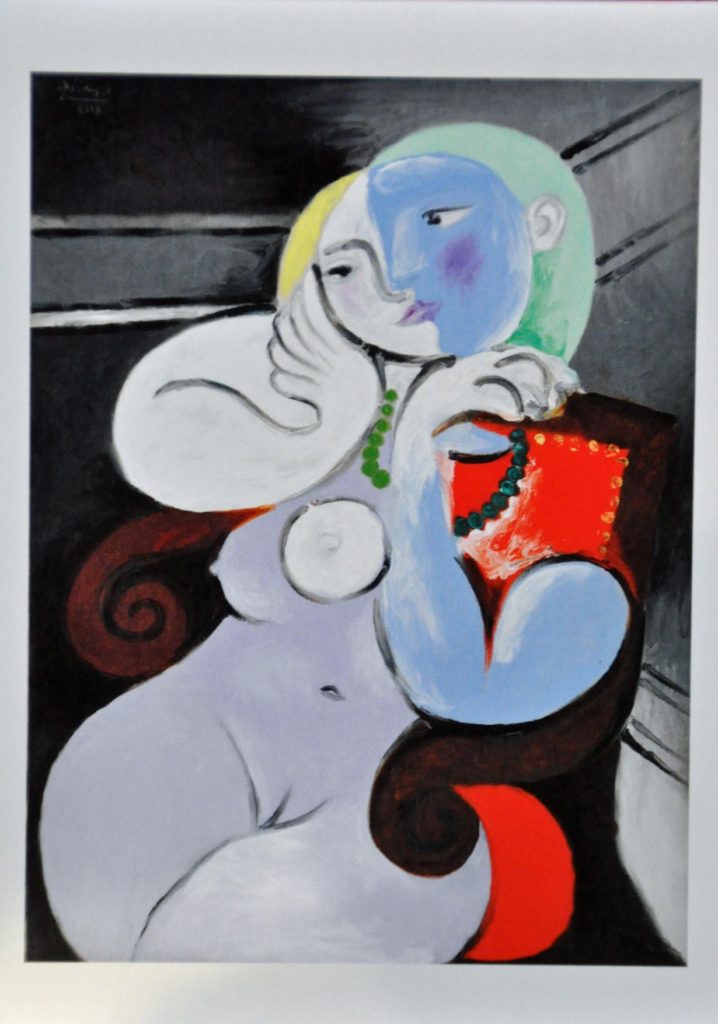

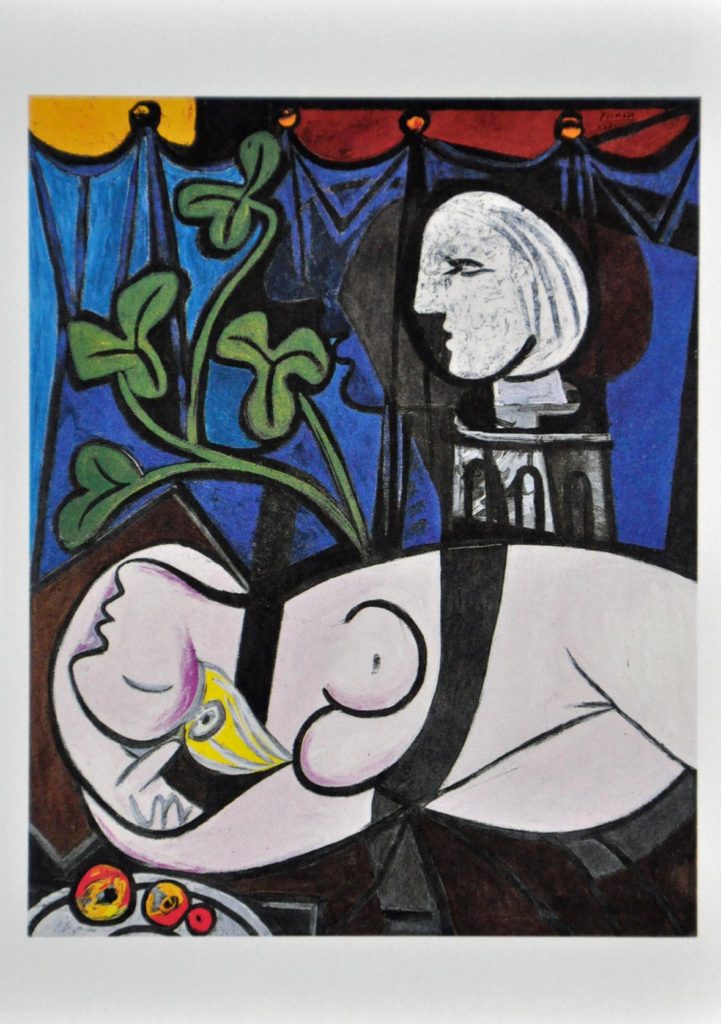

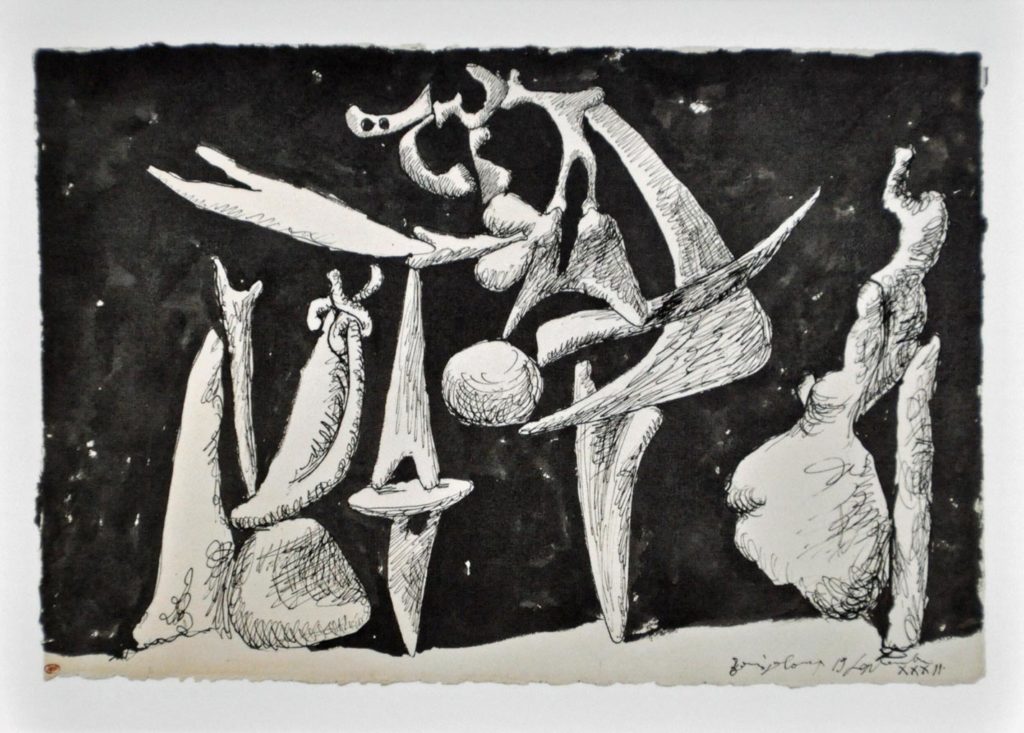

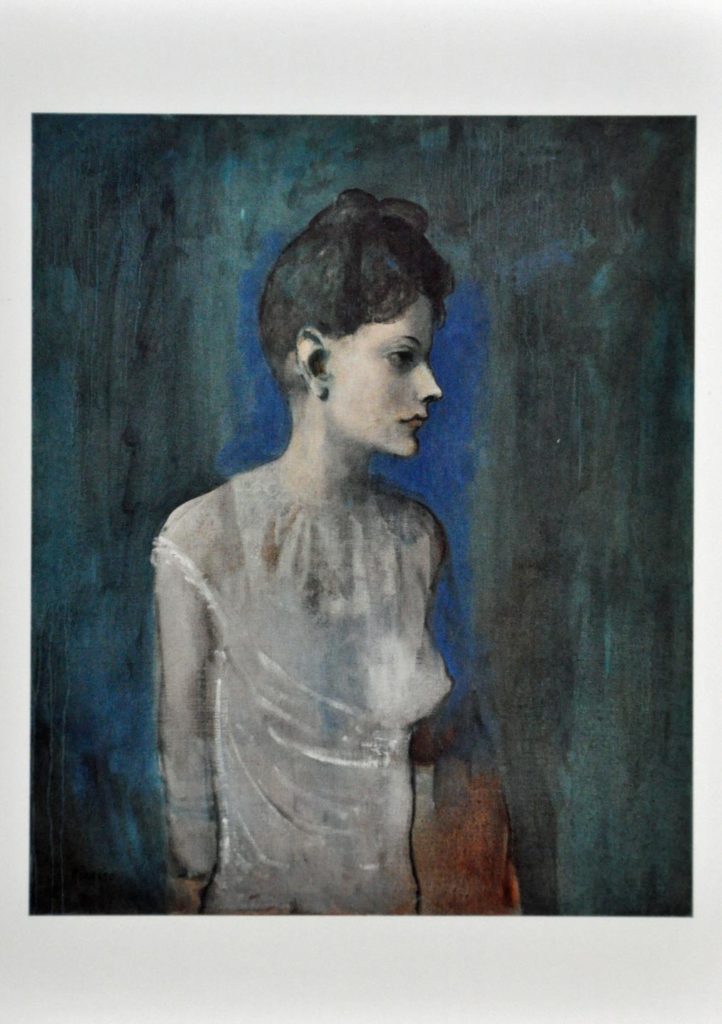

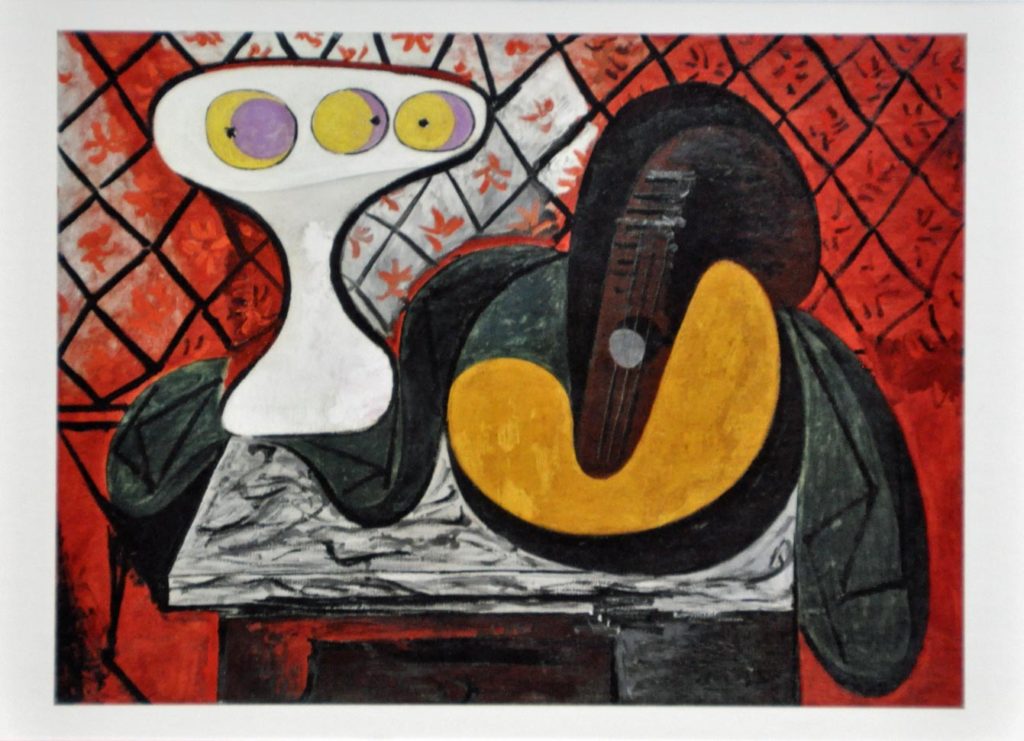

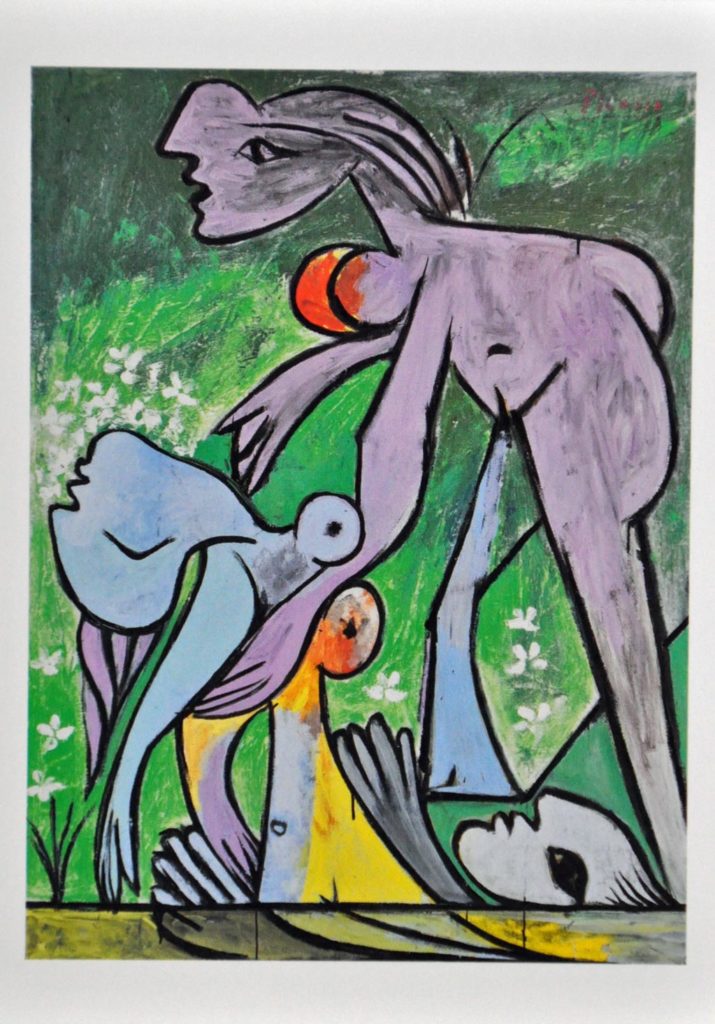

His artwork Woman with dagger is a fairly straightforward reference to the rivalry and conflict in his love life

His artwork Woman with dagger is a fairly straightforward reference to the rivalry and conflict in his love life

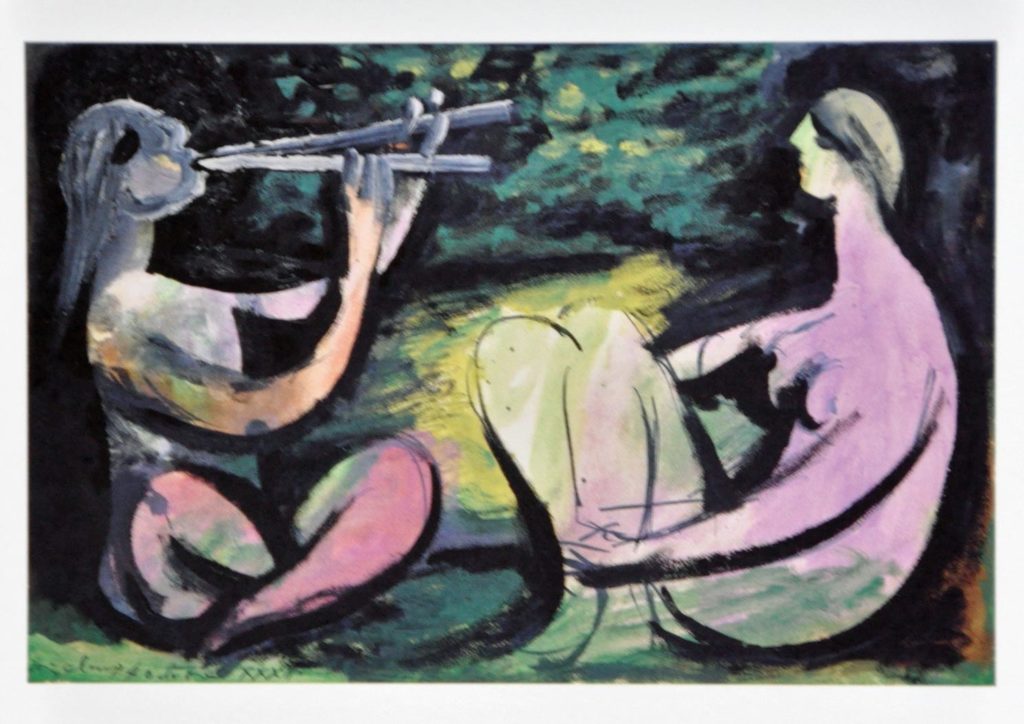

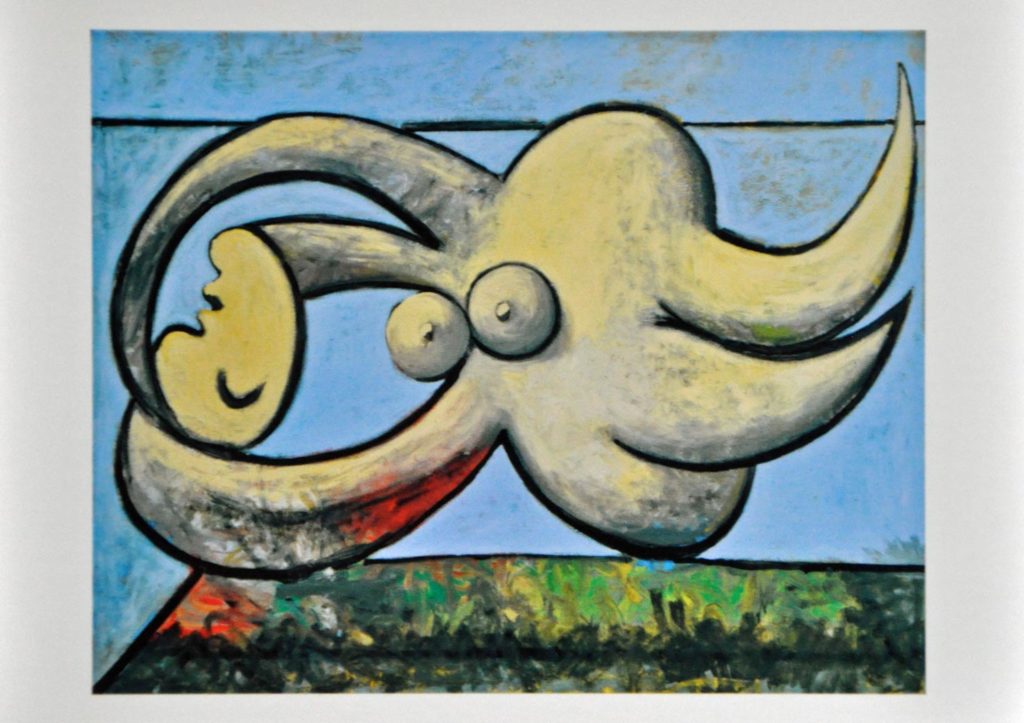

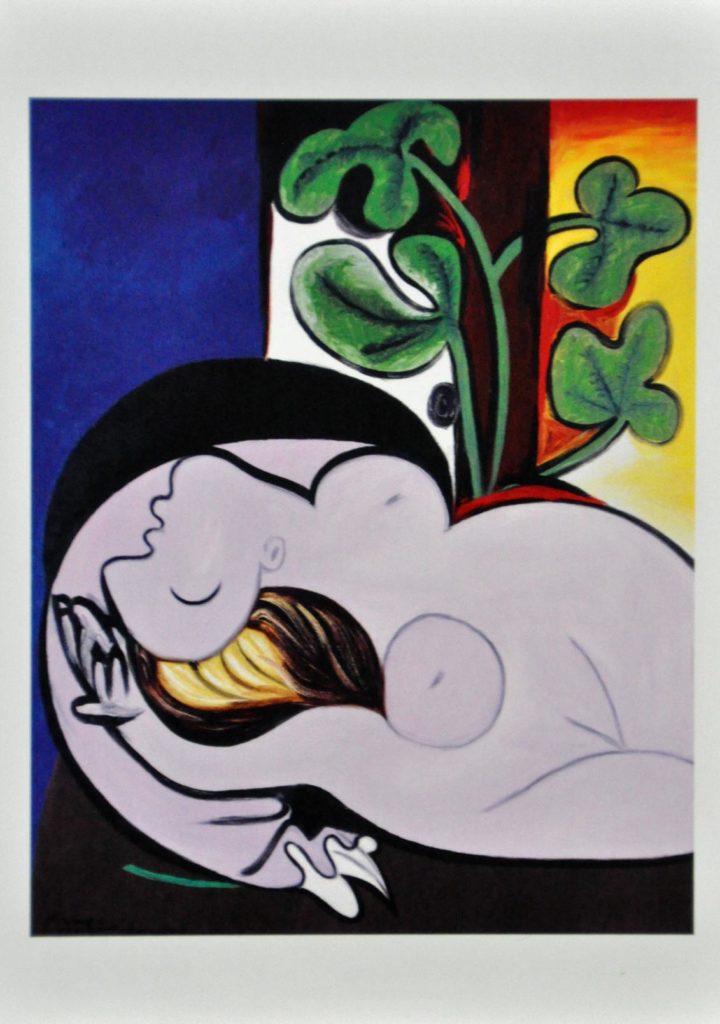

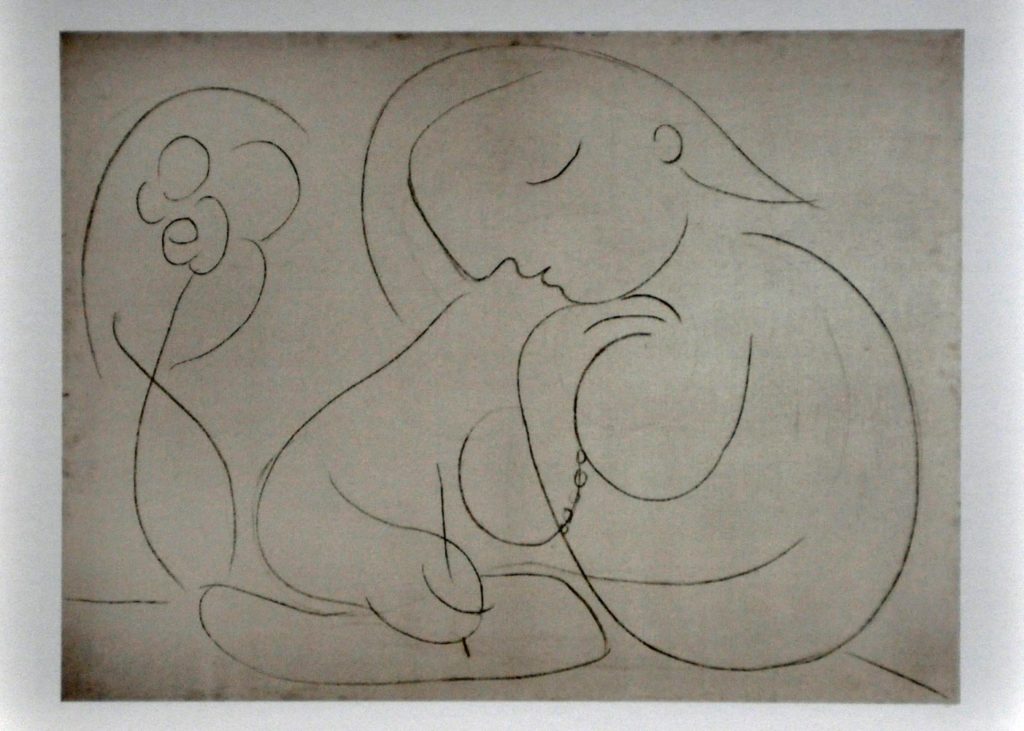

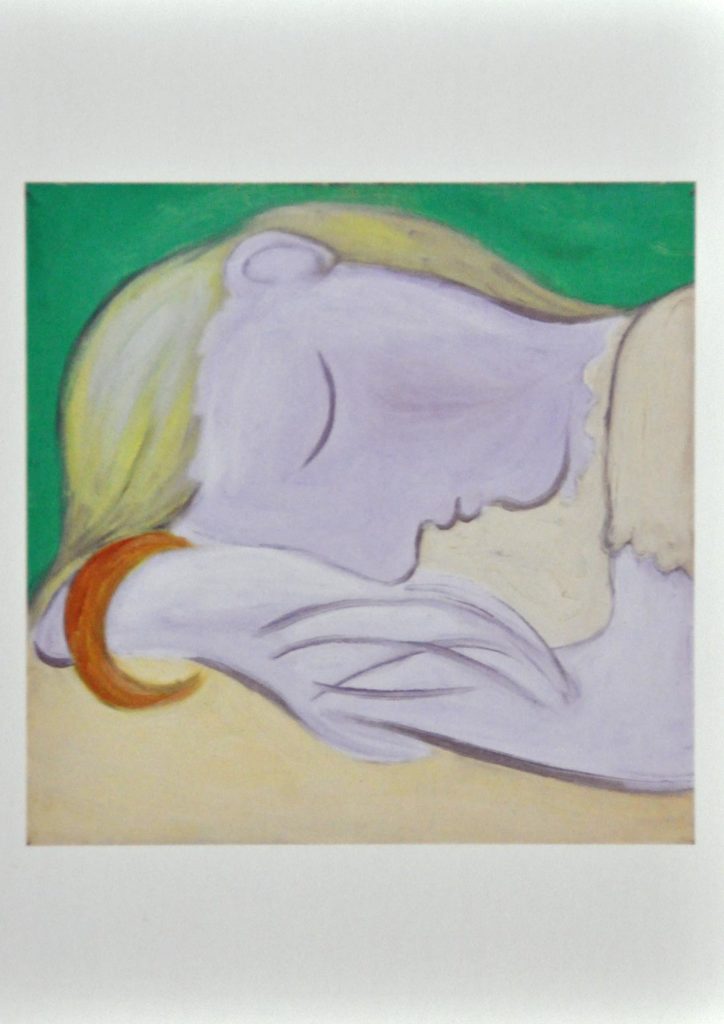

The Rescue

The Rescue