There are some things that it seems politicians can’t say wherever they hold power in the world.

Whatever politicians say, the world needs more immigration, not less pic.twitter.com/OM6TzQ45qQ

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) May 13, 2017

There are some things that it seems politicians can’t say wherever they hold power in the world.

Whatever politicians say, the world needs more immigration, not less pic.twitter.com/OM6TzQ45qQ

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) May 13, 2017

I was once told by “he who knows everything and knows it best” that my knowledge was severely limited because the UK media just plain lies. It tells lies. Where it doesn’t lie, it omits to tell the truth.

I was told this on the basis of an article this guy (it’s always a guy, isn’t it?) about football hooliganism read on a plane highlighting a problem with a UK club that this fellow followed. The violence had not been reported in the UK, or at least, nowhere where this chap had read it.

Aside from the madness of being lectured by someone who knows nothing about the media I consume, who clearly has a very limited consumption himself and on the basis of “foozball” it’s a strange idea in the modern world. Yes, there clearly is a bias within national media to report stuff that is topical and interesting and since most of the people writing in that media are from the country involved, there’s probably more of a bias than any of us recognise at the time.

We just don’t find the same things as exciting or interesting as our neighbours. So I subscribed to a number of different media from around the world and waited to be enlightened.

There really isn’t that much of a difference, truth be told. The UK is desperately interested in who gets to become next PM. No one else really cares too much. The US is desperately interested in the actions and inaction of President Trump and the machinations around the Affordable Healthcare Act. The UK less so. Der Spiegel is interested in Brexit and in the manoeuvrings of Putin, plus the rise of populism as opposed to popularity. And Australia is concerned with China more than seems right or rational to a Brit.

But then there’s some international crisis such as the malware cyber attack yesterday which has obviously had a huge impact almost everywhere, and at home has hit the NHS hard.

A new strain of ransomware — malicious software that encrypts a computer’s files and then demands payment to unlock them — spread rapidly around the world on Friday. This map shows tens of thousands of Windows computers that were taken hostage by the software, a variant of the WannaCry ransomware

Since the UK is pretty transparent about our disasters and talks about them in English, the US media has lots of information and seems to have run with the story. Most damage is said to have occurred in Russia, but translating those stories, once you’ve found them, is pretty expensive for the mainstream media outlets. So the US talks of the crappy NHS tech systems not being updated, the underlying tech code being probably sourced from code stolen by from the American secret services, the NSA, so providing both an excuse to bash the British health system (“Just look what happens with socialised medical care!) and a perverse but very real sense of pride in the amount of damage created by a dangerous American product.

In the UK, we’ve also run with the crappy NHS side of the story, because there’s nothing a Brit likes more than knocking their own society, but mitigated also by the story of a guy who sees to have become the accidental hero of the piece. The malware code included an off switch of sorts whereby the code looked up a site (non-existent domain name) for no apparent reason. A British coder, seeing this though to buy up the domain ($15) and make it live, at which point thousands of references came through to the site and virus spread was halted.

The plucky Brit saves America narrative never appears in America.

It’s a grey day, which makes the weather forecast of warmth seem just a little unbelievable. It has been the driest Spring for decades and my driest of dry gardens is not enjoying life. The plants know that they’re not going to survive a hosepipe ban later in the year given that they’re already dependant on a weekly watering.

The hanging baskets which always suffer from my laziness when it comes to watering are already starting to look reproachful and they’ve only been out there a fortnight.

On the upside, the weather is great for tennis. Dry, with no wind to blow away the clouds means we had an entirely uninterrupted three hours thrashing on the tennis courts in our first match. And afterwards when the forensics begin, obviously the first comment is just “they were better than us” and the second is to question how many of their players “played down”.

In theory, people should play to their level in these little tournaments. Where a club gains a new player though, it might not be clear how good or otherwise they might be, so some wiggle room is left. A player can play at one level for two matches, to find their feet, before settling in that division. So where we play a bigger club with two or three teams across the various divisions, the early matches are always full of ringers from divisions much further up the tree.

So it shouldn’t be a surprise that “Rose” turned out to be a regular playing in their first team last year, a team that plays two entire divisions higher than us. It’s a bit of a surprise that she was playing in pair 2 of 3, but, despite being against the spirit of the thing, it was certainly well within the legal rules.

Our next match is with a small club, like us able to pull together just a single team, so will probably play out a bit differently.

Obviously if you play a competitive game, you have to be prepared to lose with as much grace as you win.

Let’s hope we thrash them.

A friend is restructuring and replanting an entire garden in her new house. I am agitating to extending another flower bed. She is hating the whole process whilst I’m desperate to begin.

I love a good garden project.

Last year we extended the back bed and put in nine new David Austin roses. It was going to be a stretched eight, well they are reasonably expensive even bare root, but a spare arrived in the post so in it went. Sods law it turns out to be an entirely different variety but with a bit of luck…

They seem to be growing well and have coped with the narcissus and tulips for Spring. Hopefully the geranium (Roxanne Gewat) will look good underneath though I’ve also stuck in a few white gladioli and can’t quite remember where. This is why I’m a lousy gardener – too many plants and too bad a memory.

With the daffodils long gone and the tulips going over, it seems a good time to think about ordering for next year in that never-ending joy-fest of gardening with bulbs. They carry with them all of the promise of a beautiful Spring and the only downside is persuading the glum companion that an afternoon digging is worthwhile. He always loves the flowers, but not so much the dirt.

I’ve built up a wishlist on the website for PeterNijssen with as many of the ones from last year that I can remember. For under the hedge with the narcissus (a successful idea last year) I’m going to plant some tulip bakeri to follow on and hopefully cheer up the space.

And maybe if my potted up spares of the woodruff take, I’ll stick some of them down there too. The danger with the latter is that it spreads into the rest of the garden, like the thug it’s advertised as.

In the back border, along with the roses I’m going to add some black and whites so something like Queen of the Night and the white Purissima.

And I might add some under the wisteria where the tulips from last year have really brightened the place up.

In the front bed, I’m just going to abandon the colour scheme and add some scarlet tulips to the ones that already live there. I can’t get rid of them so may as well go with the flow.

In the front garden, I’m going to chuck in some soft pink tulips like an Angelique

Maybe some whites would do nicely as well but four types of tulip seems a sufficiency.

Depending on what happens to the fritillary bed (to widen or not to widen) I could add some mini-narcissus into the front, but the reality is that I have larger ambitions.

If we make the bed as big as I’d like, then I could fit some iris germanic (bearded) into the bed along with some long flowering favourites from the rest of the garden. What’s not to love about some space for yet more perennial wallflowers, some penstemons or a hardy geranium or half-hardy salvia or two?

It’s not sensible of course, I should really let one project settle, take stock and then start in on the next phase. I’m too greedy. This is why my garden will never be elegant. Fun, though!

Brexit is going to be difficult for any number of reasons.

“Civil servants are responsible for an increasingly complex range of tasks and projects.”

The National Audit Office’s first key finding highlights the difficulties faced in any modern state of delivering effective, value-for-money public services with finite resources and in an environment of technological change and increasing public expectations. The complexity of introducing comprehensive reform of the welfare system through the Universal Credit policy, and the ongoing discussions about the provision and funding of adequate social care to an ageing population are two salient illustrations of this challenge.

The government also currently has a roster of 143 highly complex, major transformative projects underway across Whitehall with estimated whole-life costs of £405bn. Each involves a range of ministries and agencies and if they are to be brought to a successful conclusion, each requires clarity of objectives, careful planning and effective whole-life project management. Each must also be delivered alongside the rest of the government’s workload.

The delivery of major projects – and specifically the management of complexity – has been an area of weakness on a number of occasions for the civil service in the past, resulting in some very significant cost over-runs (for example, Labour’s National Programme for IT). Both the NAO and the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee identify the complexity challenge as an area of particular concern.

Brexit will require the UK to untangle itself from incredibly dense and complicated legal agreements built up over 40 years. The UK government’s starting position seems to be to adopt a broad brush approach, sort out the basic idea and fill in the detail (based on trust) some time later. The EU seem to want to tie down the detail on each decision point before moving forwards to the next. Not much trust there.

“Weakness in capability undermines government’s ability to achieve its objectives […] many delivery problems can be traced to weaknesses in capability.”

Exacerbating the first challenge is that of capacity. The civil service has seen a 26% reduction in its numbers since 2006 – a reminder that while the austerity policies pursued since 2010 have had a very significant impact on capacity, the issue of resource constraints has been a longer-term problem. (Consider, for example, the major staff reductions undertaken by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office over the last decade.) As Brexit formally begins, the civil service is smaller than at any point since the end of the Second World War.

Numbers only tell part of the story, however. Accompanying this is an emerging skills deficit in three key areas – digital, commercial and delivery – that will affect the overall capacity of the civil service to meet the expectations placed upon it. The NAO believes, for example, that this capabilities gap contributed to the collapse of the InterCity West Coast franchising process in 2012, a view supported by a 2013 Transport Committee report.

Just to enable the delivery of existing programmes, the NAO suggests an additional 2,000 staff will be needed in digital roles over the next five years, at an estimated cost of between £145 million and £244 million. (The Government’s own Digital Service and Infrastructure and Projects Authority indicate the cost of filling the delivery skills deficit may actually be even greater.)

“Government projects too often go ahead without government knowing whether departments have the skills to deliver them.”

This third challenge identified very much emanates from the problems caused by the first two. The government, according to the Public Accounts Committee’s 2016 report, continually “adds to its list of activities without effective prioritisation”. When we consider some of the major projects currently underway – Crossrail/ Thameslink, Hinkley Point C, High Speed 2, and Trident Renewal – criticism by John Marzoni, Chief Executive of the Civil Service, that government is doing “30% too much to do it all well” does not seem misplaced.

A key issue has been a lack of consideration at the outsetof major projects of their overall feasibility. In particular, insufficient attention is paid to whether the requisite skills are available within departments, whether the right people are in the right posts, whether there is sufficient senior project leadership, etc. (The NAO notes that in the 2015-16 period, 22% of posts were “unfilled for senior recruitment competitions”.) Ultimately, government lacks “a clear picture of its current skills” because of insufficient workforce planning.

Moreover, efforts to remedy this problem – for example through the introduction of Single Departmental Plans – have been questioned. The NAO has therefore called on government to clearly prioritise projects and activities as a matter of urgency until it is able to fill the capability gaps outlined above.

While not addressed by the NAO report, the issue of trust in the civil service is also hugely important.

Problems of complexity, capacity and feasibility all risk fuelling feelings of scepticism that the civil service is equipped to meet the expectations placed on it. For example, Margaret Hodge, Chair of the Public Accounts Committee from 2010-2015, highlighted concerns that officials did not recognise the consequences of poor decisions: “all too often the responsible officials […] felt no sense of personal responsibility because it was not their own money.” Major IT projects were the subject of particular scepticism: “[If] any official mentioned a new IT project in their evidence to the committee, we would laugh at the idea that this might be introduced on time, within budget and save money.”

Alongside this, though, is the problem of what might be termed political trust, and particularly the perception among politicians that the civil service is unwilling to enact policies it may disagree with, something most new governments (rightly or wrongly) have been concerned with. Perhaps the most extreme recent example of this was Michael Gove’s efforts as Education Secretary in the Coalition government to implement his reforms in the face of what he and some of his own officials considered institutionalised opposition from the education establishment.

Lack of trust in the civil service’s capacity, whilst damaging, can be remedied by a government willing to prioritise change and back this up with sufficient resources. Lack of political trust, however, can be more corrosive, particularly if it results in toxic relationships between ministers and the officials responsible for enacting their policies.

The Brexit challenge:

Brexit will take up a huge amount of political and administrative bandwidth in the coming months and years. In the words of Sir Jeremy Heywood, the current Cabinet Secretary, it will be “the biggest, most complex challenge facing the civil service in our peacetime history.” It is also a microcosm of how the four key challenges of complexity, capacity, feasibility and trust have the potential, if poorly managed, to create a ‘perfect storm’ for the officials responsible for delivering it.

At the moment, the Tory Party is riding high with a weak opposition party and a free hand, but what happens if the whole thing goes tits up, no snow but four or five years down the line?

If brexit does turn out to be a disaster, it will be a Tory disaster as damaging as the Iraq War has proved for Tony Blair’s legacy. So Ms May had better get it right, better make it work.

Sometimes all you want to do is eat so soft gooey cheesy pastries straight from the oven.

There really isn’t much of a recipe beyond find a bowl, mix some cream cheese with herbs of your choice (thyme works well) and wrap the mix in some filo pastry.

Most packs of pastry come with their own advice on oven temperatures so that’s about it.

You can choose to layer the cheese between pastry sheets or just roll them into rolls and then wrap the rolls like snails.

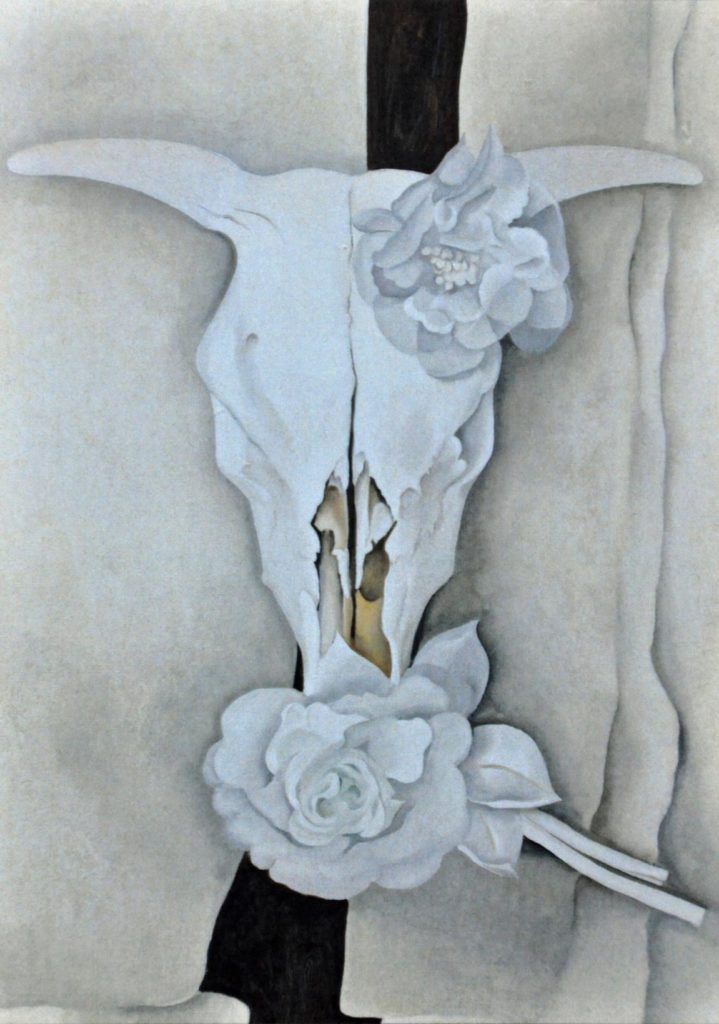

There’s a small exhibition at the RA looking at American art during the last great recession. It makes a useful contrast with the Russian Revolution Exhibition downstairs and also an interesting pre-cursor to the American Pop Art exhibition over at the British Museum (much quieter and much better value for money)

It was good but not excellent.

Not something to see if you have to pay separately for tickets rather than being a member or getting some kind of travel deal.

This is great with cheese and cold meats, served with good bread, toasted.”

Ingredients:

Method:

Put the apples, raisins, onion, mustard seeds and ginger into a large saucepan and cook gently until soft. Add the vinegar, beer and sugar, lower the heat and simmer at a mere bubble for 2–3 hours, or until all is reduced and shiny. Decant into sterilised jars and use within a month once open.

Looking through the ONS figures on tax, there are lots of useful numbers to consider.

The richest fifth of households paid £29,800 in taxes (direct and indirect) compared with £5,200 for the poorest fifth.

In 2014/15, 50.8% of all households received more in benefits (including benefits in kind) than they paid in taxes, equivalent to 13.6 million households. This continues the downward trend seen since 2010/11 (53.5%), but remains above the proportion seen before the economic downturn.

On average, households whose head was between 25 and 64 paid more in taxes than they received in benefits (including in-kind benefits) in 2014/15, whilst the reverse was true for those aged 65 and over, as the state pension starts to kick in, the largest single component of the welfare bill in the UK.

Analysis on changes in median household disposable income and other related measures, which used to form part of this report, were published earlier this year in “Household Disposable Income and Inequality, financial year ending 2015”. It looks at the various stages of redistribution of income:

The overall impact of taxes and benefits (especially the latter) are that they lead to income being shared more equally between households.

Looking at individual cash benefits, in 2014/15, the average combined amount of contribution-based and income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) received by the bottom 2 quintile groups decreased, consistent with a fall in unemployment, as well as the ongoing implementation of the Universal Credit (UC) system.

Claimants of UC and JSA are subject to the Claimant Commitment which outlines specific actions that the recipient must carry out in order to receive benefits. This may also have affected the number of households in receipt of these benefits. JSA rates, along with other working age benefits, were increased by 1% in 2014/15, below the CPI rate of inflation. The phasing out of Incapacity Benefit, Severe Disablement Allowance and Income Support paid because of illness or disability and transfer of recipients to Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) has seen average amounts received from the former benefits fall in 2014/15, whilst average amounts received from ESA have risen, reflecting the increased number of claimants.

The roll-out of Personal Independence Payment (PIP), which is replacing Disability Living Allowance (DLA) for adults aged under 65, also continued in 2014/15.

We are told that these rollouts and replacements are not cost-cutting exercises, that the government is not deliberately targeting benefits to the ill and disabled, yet that does seem to be their impact.

There was a 20.3% decrease in the amount of Child Benefit received by the richest fifth of households, due to fewer households in this part of the income distribution receiving this benefit. This is likely to be related to the High Income Benefit Charge, which may have resulted in some households electing to stop getting Child Benefit (“opt out”) rather than pay the charge. Since Child Benefit claims process is linked to my on-going entitlement to the State pension (Carers’ Allowance) , we decided to continue to claim and re-pay the tax.

Direct taxes (Income Tax, employees’ National Insurance contributions and Council Tax or Northern Ireland rates) also act to reduce inequality of income. Richer households pay both higher amounts of direct tax and a higher proportion of their income in direct taxes.

The majority of this (16.3% of gross income) was paid in Income Tax. The average tax bill for the poorest fifth of households, by contrast was equivalent to 11.0% of their gross household income. Council Tax or Northern Ireland rates made up the largest proportion of direct taxes for this group, accounting for half of all direct taxes paid by them, 5.5% of their gross income on average.

The amount of indirect tax (such as Value Added Tax (VAT) and duties on alcohol and fuel) each household pays is determined by their expenditure rather than their income. The richest fifth of households paid just over 2 and a half times as much in indirect taxes as the poorest fifth (£10,000 and £3,700 per year, respectively). This reflects greater expenditure on goods and services subject to these taxes by higher income households.

However, although richer households pay more in indirect taxes than poorer ones, they pay less as a proportion of their income (Figure 5).

This means that indirect taxes increase inequality of income.

Today, Theresa May has committed to not increasing VAT in the forthcoming parliament though obviously the highest rate set is already far in excess of the EU minimum. She obviously hasn’t committed to not extending the reach of VAT, to move more consumer goods into the VAT charge rate.

In 2014/15, the richest fifth of households paid 15.0% of their disposable income in indirect taxes, while the bottom fifth of households paid the equivalent of 29.7% of their disposable income. Across the board, VAT is the largest component of indirect taxes. Again, the proportion of disposable income that is spent on VAT is highest for the poorest fifth and lowest for the richest fifth.ce for National Statistics

Grouping households by their income is recognised as the standard approach to distributional analysis, as income provides a good indication of households’ material living standards, but it is also useful to group households according to their expenditure, particularly for examining indirect taxes, which are paid on expenditure rather than income. Some households, particularly those at the lower end of the income distribution, may have annual expenditure which exceeds their annual income. For these households, their expenditure is not being funded entirely from income. During periods of low income, these households may maintain their standard of living by funding their expenditure from savings or borrowing, thereby adjusting their lifetime consumption.

When expressed as a percentage of expenditure, the proportion paid in indirect tax declines less sharply as income rises (Figure 6) compared with the level of indirect taxes paid as a proportion of household disposable income. The bottom fifth of households paid 20.1% of their expenditure in indirect taxes compared with 17.6% for the top fifth. These figures are broadly unchanged from the previous year.

After indirect taxes, the richest fifth had post-tax household incomes that were 6 and a half times those of the poorest fifth (£56,900 compared with £8,700 per year, respectively). This ratio is unchanged on 2013/14.

The ONS also considered the effect on household income of certain benefits received in kind. Benefits in kind are goods and services provided by the government to households that are either free at the time of use or at subsidised prices, such as education and health services. These goods and services can be assigned a monetary value based on the cost to the government which is then allocated as a benefit to individual households. The poorest fifth of households received the equivalent of £7,800 per year from all benefits in kind, compared with £5,500 received by the top fifth (Effects of taxes and benefits dataset Table 2). This is partly due to households towards the bottom of the income distribution having, on average, a larger number of children in state education.

Overall, in 2014/15, 50.8% of all households received more in benefits (including in-kind benefits such as education) than they paid in taxes (direct and indirect) (Figure 7). This equates to 13.6 million households. This continues the downward trend seen since 2010/11 (53.5%) but remains above the proportions seen before the economic downturn.

The trend seen for non-retired households mirrors that for all households, except that lower percentages of non-retired households receive more in benefits than pay in taxes, 36.9% in 2014/15, down from a peak of 39.7% in 2010/11.

In contrast, in 2014/15, 88.7% of retired households received more in benefits than paid in taxes, reflecting the classification of the State Pension as a cash benefit in this analysis. A retired household is defined as a household where the income of retired household members accounts for the majority of the total household gross income2. This figure is lower than its 2009/2010 peak of 92.4% but is broadly similar to the proportions seen before the downturn.

There are a number of different ways in which inequality of household income can be presented and summarised. Perhaps the most widely used measure internationally is the Gini coefficient. Gini coefficients can vary between 0 and 100 and the lower the value, the more equally household income is distributed.

The extent to which cash benefits, direct taxes and indirect taxes together work to affect income inequality can be seen by comparing the Gini coefficients of original, gross, disposable and post-tax incomes (Effects of taxes and benefits dataset Table 10). Cash benefits have the largest impact on reducing income inequality, in 2014/15 reducing the Gini coefficient from 50.0% for original income to 35.8% for gross income (Figure 8). Direct taxes act to further reduce it, to 32.6% in 2014/15. However, indirect taxes have the opposite effect and in 2014/15 the Gini for post-tax income was 36.4%, meaning that overall, taxes have a negligible effect on income inequality.