In order to balance the books, the UK government can either raise more money through taxes or cut the amount of money it spends. For the last few decades, the emphasis has all been on cutting costs, in particular the cost of welfare though the emphasis has always been placed on culling “undeserving poor” rather than pensioners.

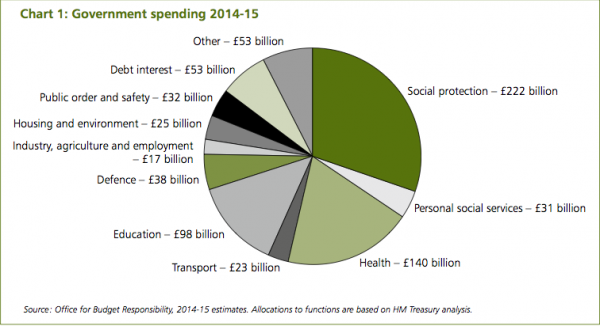

The overall breakdown of spending lumps a great deal together under the heading “social protection” which needs to be broken down further in order to understand where the money goes.

Other large areas of expenditure are health and education but these are difficult to cut without offending great swathes of the population.

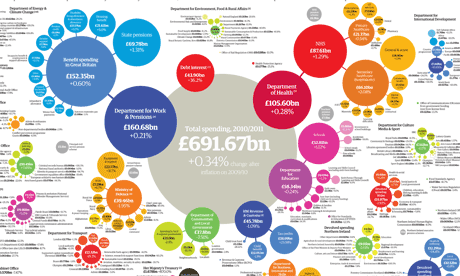

Government departments are essentially organised to manage these budgets.

The welfare budget total is temptingly large and yet political sensitivities make it difficult to cut. It’s also important to remember that the UK spends less on welfare relative to other developed countries.

The charts show that about half of welfare goes to pensioners, a very sensitive group since they are sensitive to small changes and tend to vote in significant numbers. The next largest amounts go to families with a disabled person, and support and housing for low income families,the majority of whom are in work.

Less than 1 in 5 households receive any housing benefit. Unemployment benefits make up a very small percentage of all social spending.

Currently UK pensioners are guaranteed a state pension the increases in line with the so-called triple lock, the lower of 2.5%, any increase in living costs or any increase in average wages. The amount paid is not generous at just £6,200 but still, there is no rationale for setting a minimum of 2.5% in times of low inflation and flat salaries unless you believe pensions are too low.

As a demographic group, pensioners are no longer the worst off in UK society so I would look to abandon the triple lock and reduce it to the lowest of either inflation (living costs) or salary increases.

Inflation is currently running at 0.6% whilst salaries are flat. Abandoning the commitment to 2.5% increases would save the government around £1.3m (1.9% of £70m) in the first year and potentially every year thereafter.

The story of the left ought to be a narrative of hope and progress. The greatest problem with the academic left is that it has become fundamentally aristocratic, writing in bizarre jargon that makes cliches seem abstruse. If you can’t explain your ideal to a fairly intelligent 12-year-old, it’s probably your own fault. We need a narrative that speaks to millions of ordinary people. It all starts with reclaiming the language of progress.

So we are moving into an age where people may or may not work, due neither rhyme nor reason within their own control. Jobs are increasingly temporary, precarious and either multiple or absent. Think of the technology changes that have brought us uber as a working model.

Working poverty is going to be increasing feature of our lives. Rather than rushing to reinforce a rather Calvinist view of all paid work as morally good and uplifting, in and of itself, whilst totally disregarding and undervaluing the unpaid contributions of carers everywhere, let’s reinvent the model. How? Universal basic income.

Every adult in the UK should be paid the equivalent of the standard pension ie. currently £6,200 with unto £2,000 paid for people also looking after children.

It isn’t a huge sum for an individual to live on. It is set at the amount of pension, just below the JRF estimate of a living wage (about £7,000 per person per annum) for purely political reasons: it would be impossible to justify paying more to the unemployed of working age, than to the unemployed post-retirement, even though the latter should probably be enjoying a life post mortgage with greater disposable income.

No one of working age is going to want to live on such a small amount alone. People will still find plenty of reasons to work. It is no more than a safety net that should work in our brave new precarious world.

To be practical, it’s a benefit that could only realistically be offered to British citizens, the pull factor from poorer countries would just be too big to offer it as an unconditional benefit. Currently everyone in the UK reaching the age of 18 is given a national insurance number, a universal identifier that in theory allows our tax and benefits system to work efficiently and personally. The universal income could therefore only be paid to those people living in the UK with a national insurance number, which would be dependant upon either being British born and turning 18 or living and working in the UK.

Personal taxation would require companies to pay national insurance contributions to cover the universal basic income (say £6,200) for each and every job, probably through 50% deductions of salary. At this rate an individual would have to earn £ 12,400 to cover their welfare cost.

An individual earning the equivalent of today’s average salary £27,000 pa, would more than cover any cost of this benefit for themselves – they would receive £6,200 from the state and £20,800 from their employer directly, subject to income tax rules.

The rates of tax would have to change.

Without change, the new universal credit would be deducted pre-tax, then a £10,000 tax exempt band applied and only then would the 25% tax rate be applied to £10,800. They would pay (net) just £2,700 tax rather than the current tax liability of £4,250 which would be unaffordable. If basic rate tax was increased to 40%, the tax paid under the new system would end up being much the same ie. £4,320 after receiving £6,200 from the state directly, plus £10,000 from the employer tax free, plus £6,480 taxed (£22,680).

Although an individual ends up paying very slightly more in tax, they have a lot more certainty in their income thanks to the universal income.

People are no longer able to work themselves out of the poverty they were born into. Reforms? Let’s reinvent the welfare state and eradicate poverty for good – now that’s an investment that will pay for itself.

This could be the basis of a fundamental change to the way we look at work and welfare, possibly the only practical, humane response to the changing work patterns we are seeing in the developed world. It could form the basis of a positive, socialist message, one that could be the basis of an ongoing and constructive engagement with the electorate.

Efficiency, Productivity? That should be the point of centre-left socialist policy. Every pound invested in a homeless person returns triple or more in savings on care, police and court costs. Let’s imagine what the eradication of child poverty might achieve. Solving these kinds of problems is a lot more efficient than “managing” them.

But first, the underdog socialists will have to stop wallowing in their moral superiority. Everyone who believes themselves progressive should be a beacon of not just energy but ideas, not only indignation but hope, and equal parts ethics and hard sell. Ultimately, what the underdog socialist lacks is the most vital ingredient for political change: the conviction that there truly is a better way.