POPULISM has already upended the politics of the West. Americans have elected a president who has described NATO as “obsolete” and accused China of ripping off their country. Europe’s second-largest economy, Britain, is preparing to leave the European Union (EU). But the populist revolution still has a long way to go. The far-right Sweden Democrats have been near the top of polls in a country that is synonymous with bland consensus. Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s National Front, a party that wants to take France out of the euro and hold a referendum on France’s membership of the EU, is a shoo-in for the final round of the presidential election.

Populism comes in a wide variety of flavours, left-wing as well as right-wing and smiley-faced as well as snarling. But populists are united in pitting “the people” against “the powerful”, them and us.

Spain’s left-wing Podemos bashes “la casta”, Britain’s right-wing UK Independence Party (UKIP) demonises the liberal elite, and Italy’s impossible-to-classify Beppe Grillo rails against “three destroyers—journalists, industrialists and politicians”. Populists are united in suspicion of traditional institutions, on the grounds that they have been either corrupted by the elites or left behind by technological change.

But they differ in all sorts of ways that make a populist front across political or national boundaries difficult. Right-wing populism is typically triadic, portraying the middle classes as squeezed between two outgroups, such as foreigners and welfare “spongers”. Left-wing populism is dyadic—it champions the masses against plutocratic elites or, as with Scottish nationalism, a foreign elite.

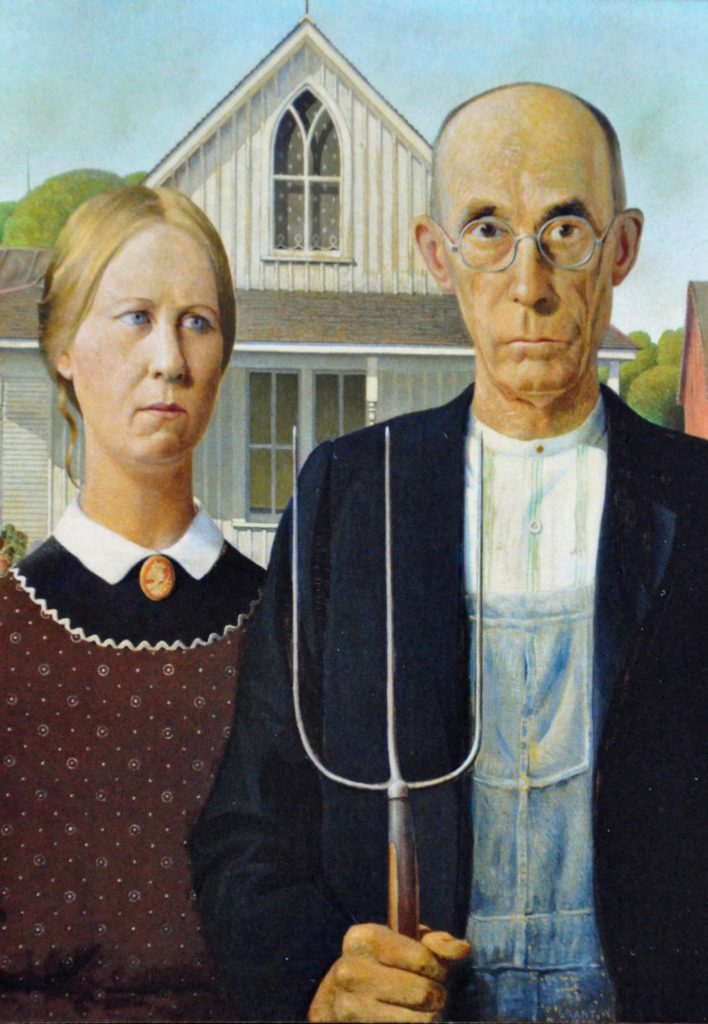

Populism was born in the prairies of the American Midwest: farmers, hit by falling grain prices and exploited by local railway monopolists, raged against “the money power” and organised new parties such as the People’s Party. The rural populists forged alliances with urban workers and middle-class progressives. They found champions in mainstream politics such as Williams Jennings Bryan, who warned against crucifying the people on a “cross of gold”, and Teddy Roosevelt, who railed against “malefactors of great wealth”.

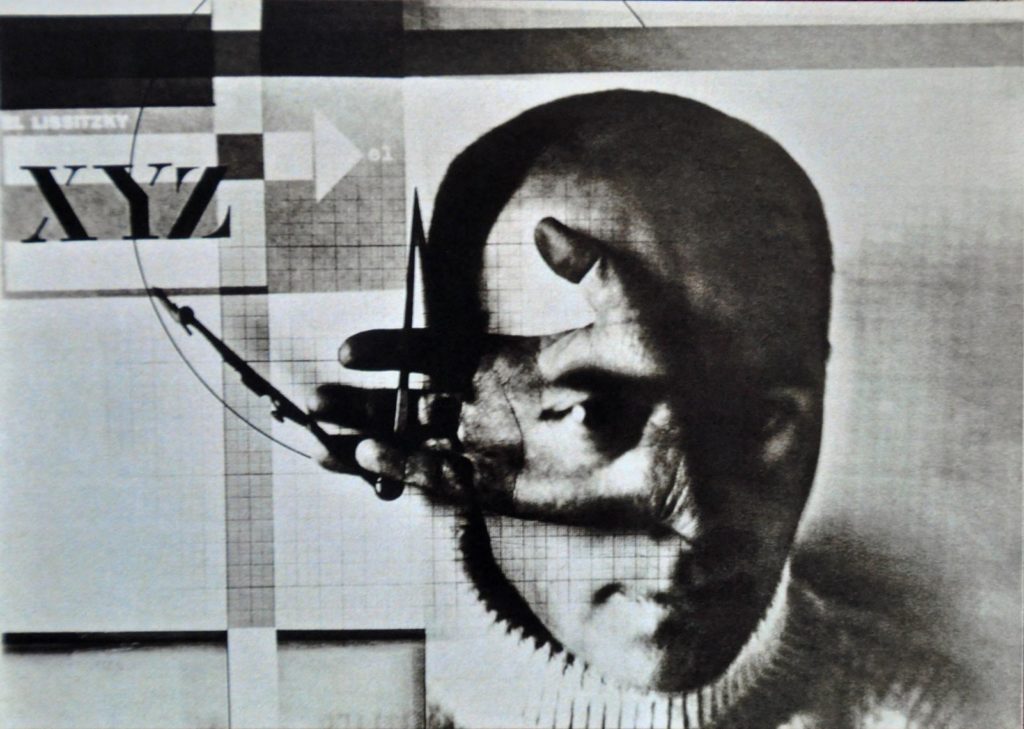

Populism profoundly shaped the 1920s and 1930s: not just in Germany and Italy (where dictators ruled in the name of the people) but also in America (where Franklin Roosevelt moved decisively to the left to head off a challenge from Huey Long, a Louisiana populist who promised “every man a king” and “a chicken in every pot”). The tendency retreated to a few islands of rage during the long post-war prosperity: France’s National Front drew its support from marginalised groups such as the pieds-noirs forced from Algeria after decolonisation, and small shopkeepers who hated paying taxes.

But populism began to revive during the stagnant 1970s: in 1976 Donald Warren, an American sociologist, announced his discovery of a group of Middle American Radicals (MARs) who believed that the American system was rigged in favour of the rich and the poor against the middle class. And it continued to grow during the long reign of pro-globalist orthodoxy: for example, Ross Perot doomed George Bush senior’s bid for a second term with a presidential campaign that prefigured many of the themes that Donald Trump has sounded more recently.

It seems that the current populist explosion is unlikely to be a mere temporary aberration: particular parties such as UKIP may implode, but the tendency draws on a deep well of discontent with the status quo. Technocratic elites lost much of their credibility in the global financial crisis in 2008. The EU has damaged its claim to be a guardian of democracy against populist extremists by repeatedly ignoring referendums in which voters rejected new treaties.

The populists have shown a genius for taking worries that contain a nugget of truth—such as that unrestricted immigration is destabilising—and turning them into vote-winning platforms. And they have relentlessly broadened and deepened their appeal as establishment politicians have marginalised the issues that give them life, for example treating worries about migration as nothing but racism. France’s National Front, the most mature of all the populist parties, has already extended its constituency from small businesses to blue-collar workers, pocketing districts that were once dominated by the left and now extending its appeal to public-sector workers.

Some blinkered commentators still see populism as no more than a protest movement: dangerous and disruptive but ultimately doomed by the advance of globalisation and multiculturalism, which are in turn driven by irreversible technological and demographic forces. A glance at history suggests that this view is questionable.

Globalisation went into rapid reverse in the 1920s and 1930s despite the spread of aeroplanes and telephones. The proportion of Americans born abroad was 13.4% in 1920, but after the Immigration Act of 1924 that fell, reaching 4.7% in 1970. The Western elite may be as wrong about the long-term impact of populism as it has been about its short-term prospects.

We are where we are. What happens when populism doesn’t provide the answers that people are looking for? Even worse, what happens if it does?