Amidst the recriminations and collective shock in the face of Trump’s victory (and the myriad other reverses suffered by progressives in 2016), a consensus is emerging: the weakness of the left is attributable to its embrace of “identity politics”.

Rather than focussing on the interests and priorities of the majority, the story goes, the left has for too long embraced a simplistic and sectional politics in which the interests of racial and sexual minorities have taken centre stage, at the expense popularity and electability.

A recent outburst from the perhaps unlikely figure of Stephen Kinnock typifies this narrative. “What we need to see in the progressive Left is an end to this identity politics”. & in its place “we need to be talking far more about commonality rather than what differentiates from each other – let’s talk about what unites us.”

Similar pronouncements have recently been made by Bernie Sanders, as well as a number of left-liberal commentators on both sides of the Atlantic.

However, this unease about so-called “identity politics” has been a longstanding feature of left commentary and scholarship.This disdain for identity politics is not isolated to a few individuals: it is a widespread sensibility expressed by Marxists and left-liberals alike

But what, precisely, is this “identity politics” that inspires such animosity?

At a basic level, “identity politics” refers to any politics that seeks to represent and/or advance the claims of a particular social group. But in the narratives outlined above, it has a more specific meaning: in left circles, “identity politics” is, as Nancy Fraser pointed out back in 1998, used largely as a derogatory term for feminism, anti-racism and anti-heterosexism.

The implication was – and very often still is – that gender, race and sexuality are identity-based in the sense that they are seen as flimsy, superficial and, to use Judith Butler’s memorable phrase, ‘merely cultural’.

This is contrasted with its constitutive outside, class. Class relations, in the eyes of the identity politics critic, exhibit a depth, profundity and materiality that ‘mere identity’ lacks. Furthermore, the alleged universalism of class is contrasted with the narrow, sectional concerns characteristic of so-called identity politics.

But what, precisely, is wrong with this framing of the problem?

To start with, the implied distinction between “identity” (read: narrow, shallow, self-interested) and “class” politics (read: broad, deep, universal, authentic) misconstrues the character of these different strands of progressive politics, in at least three ways.

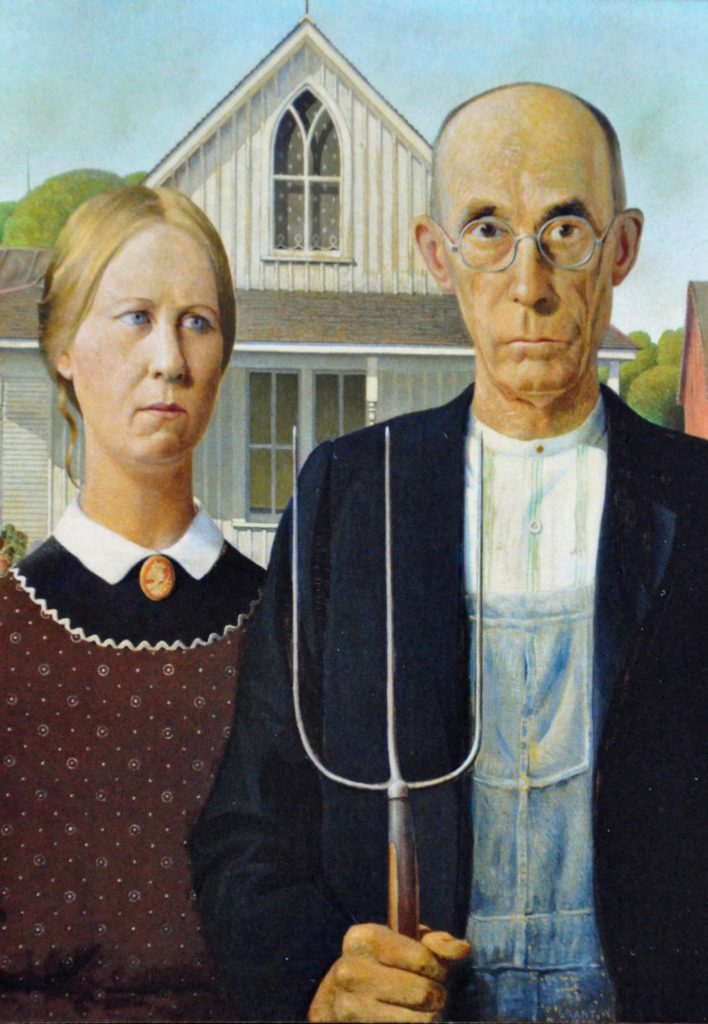

All forms of politics arguably involve some kind of appeal to an identity, insofar as they clearly involve claims to speak for a politically salient constituency (and thus an “identity” of sorts). This applies as much to “class” as any other dimension of power and identity. Indeed, these appeals to “class” are quintessential identity politics: they appeal to an identity category – the (presumed white) working class – whose interests have been shamefully neglected by elitist, out of touch leftists and liberals.

The question is not, therefore, universalism or identitarianism, but whether or not we acknowledge the “identitarian” character of our political claims. Something akin to this is eloquently described by James Clifford in a 1999 essay entitled ‘Taking Identity Politics Seriously’, where he argues that ‘opposition to the special claims of racial or ethnic minorities often masks another, unmarked ‘identity politics’, an actively sustained historical positioning and possessive investment in Whiteness’.

Few contemporary feminists or anti-racists would adopt the view that one’s identity necessarily gives rise to specific forms of politics. Indeed, the recent history of feminism, queer politics and anti-racism is precisely one of challenging identity by analysing and questioning the various ways in which heteronormativity, capitalism, white supremacy and patriarchy shape identity-formation.

Basically there is a frankly bewildering inference made by Pinnock et al that the left in its various guises has spent its time of late doggedly pursuing the interests of women, sexual minorities and racial minorities. The reality, however, is that left-wing movements and political parties in the UK and US have an at best patchy track records on race, gender and sexuality, as recent scholarship by the likes of Janet Conway, Julia Downes, Lara Coleman and Abigail Bakan make clear.

All the way from the moderate liberal left to the radical Marxist left, race, gender and sexuality continue to be cast as minority concerns at best, and “bourgeois distractions” at worst, while sexism and misogyny (including, but not limited to, the sexual abuse of women comrades) remain depressingly prevalent across a variety of left spaces.

Consequently, left-wing denunciations of identity politics yield a number of alarming consequences: they naturalise gendered and racialised hierarchies by casting white, male class politics as universal. Such a narrative is therefore not only powerless to challenge, but actively complicit in, the re-energised white supremacism which, as Akwugo Emejulu has recently outlined, has been fundamental to the context of Trump’s victory.

What is more, to pit class politics against identity politics casts women, racial minorities and sexual minorities as outside the boundaries of true, authentic “working classness”. As such, the political claims of working class ethnic minorities, queers and women increasingly go unheard. This is exacerbated by the continued use of “left behind” as euphemism for “white working class”, with its inference that white poverty is unnatural, exceptional, worthy of our attention, while black poverty is either invisible or simply part of the natural order of things. Who is seen to “count” as authentically working class has thus become a key terrain of struggle in the era of Trump and Brexit.

Let us, therefore, not be under any illusions about how these dismissals of “identity politics” function: they are, in effect, a kind of dog whistle to those on the left who might, for instance, agree that black lives matter, but ultimately believe that when push comes to shove it is the (white male) working class that matters more.

As others have pointed out, this is tantamount to being called upon to sacrifice a range of constituencies – women, racial minorities, queers, immigrants (and at times perhaps also trans people, non-binary and gender non-conforming folk, sex workers) – on the altar of political expediency. Putting aside any doubts as to whether this would actually work in terms of galvanising electoral support, this is clearly a morally bankrupt form of politics.

Any solution that insists we forget, minimise or ignore the disadvantage of those who are not white and male is not one I want to sign up to.