There are some things that it seems politicians can’t say wherever they hold power in the world.

Whatever politicians say, the world needs more immigration, not less pic.twitter.com/OM6TzQ45qQ

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) May 13, 2017

There are some things that it seems politicians can’t say wherever they hold power in the world.

Whatever politicians say, the world needs more immigration, not less pic.twitter.com/OM6TzQ45qQ

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) May 13, 2017

Brexit is going to be difficult for any number of reasons.

“Civil servants are responsible for an increasingly complex range of tasks and projects.”

The National Audit Office’s first key finding highlights the difficulties faced in any modern state of delivering effective, value-for-money public services with finite resources and in an environment of technological change and increasing public expectations. The complexity of introducing comprehensive reform of the welfare system through the Universal Credit policy, and the ongoing discussions about the provision and funding of adequate social care to an ageing population are two salient illustrations of this challenge.

The government also currently has a roster of 143 highly complex, major transformative projects underway across Whitehall with estimated whole-life costs of £405bn. Each involves a range of ministries and agencies and if they are to be brought to a successful conclusion, each requires clarity of objectives, careful planning and effective whole-life project management. Each must also be delivered alongside the rest of the government’s workload.

The delivery of major projects – and specifically the management of complexity – has been an area of weakness on a number of occasions for the civil service in the past, resulting in some very significant cost over-runs (for example, Labour’s National Programme for IT). Both the NAO and the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee identify the complexity challenge as an area of particular concern.

Brexit will require the UK to untangle itself from incredibly dense and complicated legal agreements built up over 40 years. The UK government’s starting position seems to be to adopt a broad brush approach, sort out the basic idea and fill in the detail (based on trust) some time later. The EU seem to want to tie down the detail on each decision point before moving forwards to the next. Not much trust there.

“Weakness in capability undermines government’s ability to achieve its objectives […] many delivery problems can be traced to weaknesses in capability.”

Exacerbating the first challenge is that of capacity. The civil service has seen a 26% reduction in its numbers since 2006 – a reminder that while the austerity policies pursued since 2010 have had a very significant impact on capacity, the issue of resource constraints has been a longer-term problem. (Consider, for example, the major staff reductions undertaken by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office over the last decade.) As Brexit formally begins, the civil service is smaller than at any point since the end of the Second World War.

Numbers only tell part of the story, however. Accompanying this is an emerging skills deficit in three key areas – digital, commercial and delivery – that will affect the overall capacity of the civil service to meet the expectations placed upon it. The NAO believes, for example, that this capabilities gap contributed to the collapse of the InterCity West Coast franchising process in 2012, a view supported by a 2013 Transport Committee report.

Just to enable the delivery of existing programmes, the NAO suggests an additional 2,000 staff will be needed in digital roles over the next five years, at an estimated cost of between £145 million and £244 million. (The Government’s own Digital Service and Infrastructure and Projects Authority indicate the cost of filling the delivery skills deficit may actually be even greater.)

“Government projects too often go ahead without government knowing whether departments have the skills to deliver them.”

This third challenge identified very much emanates from the problems caused by the first two. The government, according to the Public Accounts Committee’s 2016 report, continually “adds to its list of activities without effective prioritisation”. When we consider some of the major projects currently underway – Crossrail/ Thameslink, Hinkley Point C, High Speed 2, and Trident Renewal – criticism by John Marzoni, Chief Executive of the Civil Service, that government is doing “30% too much to do it all well” does not seem misplaced.

A key issue has been a lack of consideration at the outsetof major projects of their overall feasibility. In particular, insufficient attention is paid to whether the requisite skills are available within departments, whether the right people are in the right posts, whether there is sufficient senior project leadership, etc. (The NAO notes that in the 2015-16 period, 22% of posts were “unfilled for senior recruitment competitions”.) Ultimately, government lacks “a clear picture of its current skills” because of insufficient workforce planning.

Moreover, efforts to remedy this problem – for example through the introduction of Single Departmental Plans – have been questioned. The NAO has therefore called on government to clearly prioritise projects and activities as a matter of urgency until it is able to fill the capability gaps outlined above.

While not addressed by the NAO report, the issue of trust in the civil service is also hugely important.

Problems of complexity, capacity and feasibility all risk fuelling feelings of scepticism that the civil service is equipped to meet the expectations placed on it. For example, Margaret Hodge, Chair of the Public Accounts Committee from 2010-2015, highlighted concerns that officials did not recognise the consequences of poor decisions: “all too often the responsible officials […] felt no sense of personal responsibility because it was not their own money.” Major IT projects were the subject of particular scepticism: “[If] any official mentioned a new IT project in their evidence to the committee, we would laugh at the idea that this might be introduced on time, within budget and save money.”

Alongside this, though, is the problem of what might be termed political trust, and particularly the perception among politicians that the civil service is unwilling to enact policies it may disagree with, something most new governments (rightly or wrongly) have been concerned with. Perhaps the most extreme recent example of this was Michael Gove’s efforts as Education Secretary in the Coalition government to implement his reforms in the face of what he and some of his own officials considered institutionalised opposition from the education establishment.

Lack of trust in the civil service’s capacity, whilst damaging, can be remedied by a government willing to prioritise change and back this up with sufficient resources. Lack of political trust, however, can be more corrosive, particularly if it results in toxic relationships between ministers and the officials responsible for enacting their policies.

The Brexit challenge:

Brexit will take up a huge amount of political and administrative bandwidth in the coming months and years. In the words of Sir Jeremy Heywood, the current Cabinet Secretary, it will be “the biggest, most complex challenge facing the civil service in our peacetime history.” It is also a microcosm of how the four key challenges of complexity, capacity, feasibility and trust have the potential, if poorly managed, to create a ‘perfect storm’ for the officials responsible for delivering it.

At the moment, the Tory Party is riding high with a weak opposition party and a free hand, but what happens if the whole thing goes tits up, no snow but four or five years down the line?

If brexit does turn out to be a disaster, it will be a Tory disaster as damaging as the Iraq War has proved for Tony Blair’s legacy. So Ms May had better get it right, better make it work.

Looking through the ONS figures on tax, there are lots of useful numbers to consider.

The richest fifth of households paid £29,800 in taxes (direct and indirect) compared with £5,200 for the poorest fifth.

In 2014/15, 50.8% of all households received more in benefits (including benefits in kind) than they paid in taxes, equivalent to 13.6 million households. This continues the downward trend seen since 2010/11 (53.5%), but remains above the proportion seen before the economic downturn.

On average, households whose head was between 25 and 64 paid more in taxes than they received in benefits (including in-kind benefits) in 2014/15, whilst the reverse was true for those aged 65 and over, as the state pension starts to kick in, the largest single component of the welfare bill in the UK.

Analysis on changes in median household disposable income and other related measures, which used to form part of this report, were published earlier this year in “Household Disposable Income and Inequality, financial year ending 2015”. It looks at the various stages of redistribution of income:

The overall impact of taxes and benefits (especially the latter) are that they lead to income being shared more equally between households.

Looking at individual cash benefits, in 2014/15, the average combined amount of contribution-based and income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) received by the bottom 2 quintile groups decreased, consistent with a fall in unemployment, as well as the ongoing implementation of the Universal Credit (UC) system.

Claimants of UC and JSA are subject to the Claimant Commitment which outlines specific actions that the recipient must carry out in order to receive benefits. This may also have affected the number of households in receipt of these benefits. JSA rates, along with other working age benefits, were increased by 1% in 2014/15, below the CPI rate of inflation. The phasing out of Incapacity Benefit, Severe Disablement Allowance and Income Support paid because of illness or disability and transfer of recipients to Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) has seen average amounts received from the former benefits fall in 2014/15, whilst average amounts received from ESA have risen, reflecting the increased number of claimants.

The roll-out of Personal Independence Payment (PIP), which is replacing Disability Living Allowance (DLA) for adults aged under 65, also continued in 2014/15.

We are told that these rollouts and replacements are not cost-cutting exercises, that the government is not deliberately targeting benefits to the ill and disabled, yet that does seem to be their impact.

There was a 20.3% decrease in the amount of Child Benefit received by the richest fifth of households, due to fewer households in this part of the income distribution receiving this benefit. This is likely to be related to the High Income Benefit Charge, which may have resulted in some households electing to stop getting Child Benefit (“opt out”) rather than pay the charge. Since Child Benefit claims process is linked to my on-going entitlement to the State pension (Carers’ Allowance) , we decided to continue to claim and re-pay the tax.

Direct taxes (Income Tax, employees’ National Insurance contributions and Council Tax or Northern Ireland rates) also act to reduce inequality of income. Richer households pay both higher amounts of direct tax and a higher proportion of their income in direct taxes.

The majority of this (16.3% of gross income) was paid in Income Tax. The average tax bill for the poorest fifth of households, by contrast was equivalent to 11.0% of their gross household income. Council Tax or Northern Ireland rates made up the largest proportion of direct taxes for this group, accounting for half of all direct taxes paid by them, 5.5% of their gross income on average.

The amount of indirect tax (such as Value Added Tax (VAT) and duties on alcohol and fuel) each household pays is determined by their expenditure rather than their income. The richest fifth of households paid just over 2 and a half times as much in indirect taxes as the poorest fifth (£10,000 and £3,700 per year, respectively). This reflects greater expenditure on goods and services subject to these taxes by higher income households.

However, although richer households pay more in indirect taxes than poorer ones, they pay less as a proportion of their income (Figure 5).

This means that indirect taxes increase inequality of income.

Today, Theresa May has committed to not increasing VAT in the forthcoming parliament though obviously the highest rate set is already far in excess of the EU minimum. She obviously hasn’t committed to not extending the reach of VAT, to move more consumer goods into the VAT charge rate.

In 2014/15, the richest fifth of households paid 15.0% of their disposable income in indirect taxes, while the bottom fifth of households paid the equivalent of 29.7% of their disposable income. Across the board, VAT is the largest component of indirect taxes. Again, the proportion of disposable income that is spent on VAT is highest for the poorest fifth and lowest for the richest fifth.ce for National Statistics

Grouping households by their income is recognised as the standard approach to distributional analysis, as income provides a good indication of households’ material living standards, but it is also useful to group households according to their expenditure, particularly for examining indirect taxes, which are paid on expenditure rather than income. Some households, particularly those at the lower end of the income distribution, may have annual expenditure which exceeds their annual income. For these households, their expenditure is not being funded entirely from income. During periods of low income, these households may maintain their standard of living by funding their expenditure from savings or borrowing, thereby adjusting their lifetime consumption.

When expressed as a percentage of expenditure, the proportion paid in indirect tax declines less sharply as income rises (Figure 6) compared with the level of indirect taxes paid as a proportion of household disposable income. The bottom fifth of households paid 20.1% of their expenditure in indirect taxes compared with 17.6% for the top fifth. These figures are broadly unchanged from the previous year.

After indirect taxes, the richest fifth had post-tax household incomes that were 6 and a half times those of the poorest fifth (£56,900 compared with £8,700 per year, respectively). This ratio is unchanged on 2013/14.

The ONS also considered the effect on household income of certain benefits received in kind. Benefits in kind are goods and services provided by the government to households that are either free at the time of use or at subsidised prices, such as education and health services. These goods and services can be assigned a monetary value based on the cost to the government which is then allocated as a benefit to individual households. The poorest fifth of households received the equivalent of £7,800 per year from all benefits in kind, compared with £5,500 received by the top fifth (Effects of taxes and benefits dataset Table 2). This is partly due to households towards the bottom of the income distribution having, on average, a larger number of children in state education.

Overall, in 2014/15, 50.8% of all households received more in benefits (including in-kind benefits such as education) than they paid in taxes (direct and indirect) (Figure 7). This equates to 13.6 million households. This continues the downward trend seen since 2010/11 (53.5%) but remains above the proportions seen before the economic downturn.

The trend seen for non-retired households mirrors that for all households, except that lower percentages of non-retired households receive more in benefits than pay in taxes, 36.9% in 2014/15, down from a peak of 39.7% in 2010/11.

In contrast, in 2014/15, 88.7% of retired households received more in benefits than paid in taxes, reflecting the classification of the State Pension as a cash benefit in this analysis. A retired household is defined as a household where the income of retired household members accounts for the majority of the total household gross income2. This figure is lower than its 2009/2010 peak of 92.4% but is broadly similar to the proportions seen before the downturn.

There are a number of different ways in which inequality of household income can be presented and summarised. Perhaps the most widely used measure internationally is the Gini coefficient. Gini coefficients can vary between 0 and 100 and the lower the value, the more equally household income is distributed.

The extent to which cash benefits, direct taxes and indirect taxes together work to affect income inequality can be seen by comparing the Gini coefficients of original, gross, disposable and post-tax incomes (Effects of taxes and benefits dataset Table 10). Cash benefits have the largest impact on reducing income inequality, in 2014/15 reducing the Gini coefficient from 50.0% for original income to 35.8% for gross income (Figure 8). Direct taxes act to further reduce it, to 32.6% in 2014/15. However, indirect taxes have the opposite effect and in 2014/15 the Gini for post-tax income was 36.4%, meaning that overall, taxes have a negligible effect on income inequality.

1) May had said she wanted to talk not just Brexit but also world problems; but in practice it fell to Juncker to propose one to discuss.

2) May has made clear to the Commission that she fully expects to be reelected as PM.

3) It is thought [in the Commission] that May wants to frustrate the daily business of the EU27, to improve her own negotiating position.

4) May seemed pissed off at Davis for regaling her dinner guests of his ECJ case against her data retention measures – three times.

5) EU side were astonished at May’s suggestion that EU/UK expats issue could be sorted at EU Council meeting at the end of June.

6) Juncker objected to this timetable as way too optimistic given complexities, eg on rights to health care.

7) Juncker pulled two piles of paper from his bag: Croatia’s EU entry deal, Canada’s free trade deal. His point: Brexit will be v v complex.

10) EU side felt May was seeing whole thing through rose-tinted-glasses. “Let us make Brexit a success” she told them.

11) Juncker countered that Britain will now be a third state, not even (like Turkey) in the customs union: “Brexit cannot be a success”.

12) May seemed surprised by this and seemed to the EU side not to have been fully briefed.

13) She cited her own JHA opt-out negotiations as home sec as a model: a mutually useful agreement meaning lots on paper, little in reality.

14) May’s reference to the JHA (justice and home affairs) opt-outs set off alarm signals for the EU side. This was what they had feared.

16) “The more I hear, the more sceptical I become” said Juncker (this was only half way through the dinner)

19) Davis then objected that EU could not force a post-Brexit, post-ECJ UK to pay the bill. OK, said Juncker, then no trade deal.

20) …leaving EU27 with UK’s unpaid bills will involve national parliaments in process (a point that Berlin had made *repeatedly* before).

21) “I leave Downing St ten times as sceptical as I was before” Juncker told May as he left

22) Next morning at c7am Juncker called Merkel on her mobile, said May living in another galaxy & totally deluding herself

23) Merkel quickly reworked her speech to Bundestag to include her now-famous “some in Britain still have illusions” comment

24) FAZ concludes: May in election mode & playing to crowd, but what use is a big majority won by nurturing delusions of Brexit hardliners?

25) Juncker’s team now think it more likely than not that Brexit talks will collapse & hope Brits wake up to harsh realities in time.

26) What to make of it all? Obviously this leak is a highly tactical move by Commission. But contents deeply worrying for UK nonetheless.

27) The report points to major communications/briefing problems. Important messages from Berlin & Brussels seem not to be getting through.

28) Presumably as a result, May seems to be labouring under some really rather fundamental misconceptions about Brexit & the EU27.

29) Also clear that (as some of us have been warning for a while…) No 10 should expect every detail of the Brexit talks to leak.

30/30) Sorry for the long thread. And a reminder: full credit for all the above reporting on the May/Juncker dinner goes to the FAZ

POPULISM has already upended the politics of the West. Americans have elected a president who has described NATO as “obsolete” and accused China of ripping off their country. Europe’s second-largest economy, Britain, is preparing to leave the European Union (EU). But the populist revolution still has a long way to go. The far-right Sweden Democrats have been near the top of polls in a country that is synonymous with bland consensus. Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s National Front, a party that wants to take France out of the euro and hold a referendum on France’s membership of the EU, is a shoo-in for the final round of the presidential election.

Populism comes in a wide variety of flavours, left-wing as well as right-wing and smiley-faced as well as snarling. But populists are united in pitting “the people” against “the powerful”, them and us.

Spain’s left-wing Podemos bashes “la casta”, Britain’s right-wing UK Independence Party (UKIP) demonises the liberal elite, and Italy’s impossible-to-classify Beppe Grillo rails against “three destroyers—journalists, industrialists and politicians”. Populists are united in suspicion of traditional institutions, on the grounds that they have been either corrupted by the elites or left behind by technological change.

But they differ in all sorts of ways that make a populist front across political or national boundaries difficult. Right-wing populism is typically triadic, portraying the middle classes as squeezed between two outgroups, such as foreigners and welfare “spongers”. Left-wing populism is dyadic—it champions the masses against plutocratic elites or, as with Scottish nationalism, a foreign elite.

Populism was born in the prairies of the American Midwest: farmers, hit by falling grain prices and exploited by local railway monopolists, raged against “the money power” and organised new parties such as the People’s Party. The rural populists forged alliances with urban workers and middle-class progressives. They found champions in mainstream politics such as Williams Jennings Bryan, who warned against crucifying the people on a “cross of gold”, and Teddy Roosevelt, who railed against “malefactors of great wealth”.

Populism profoundly shaped the 1920s and 1930s: not just in Germany and Italy (where dictators ruled in the name of the people) but also in America (where Franklin Roosevelt moved decisively to the left to head off a challenge from Huey Long, a Louisiana populist who promised “every man a king” and “a chicken in every pot”). The tendency retreated to a few islands of rage during the long post-war prosperity: France’s National Front drew its support from marginalised groups such as the pieds-noirs forced from Algeria after decolonisation, and small shopkeepers who hated paying taxes.

But populism began to revive during the stagnant 1970s: in 1976 Donald Warren, an American sociologist, announced his discovery of a group of Middle American Radicals (MARs) who believed that the American system was rigged in favour of the rich and the poor against the middle class. And it continued to grow during the long reign of pro-globalist orthodoxy: for example, Ross Perot doomed George Bush senior’s bid for a second term with a presidential campaign that prefigured many of the themes that Donald Trump has sounded more recently.

It seems that the current populist explosion is unlikely to be a mere temporary aberration: particular parties such as UKIP may implode, but the tendency draws on a deep well of discontent with the status quo. Technocratic elites lost much of their credibility in the global financial crisis in 2008. The EU has damaged its claim to be a guardian of democracy against populist extremists by repeatedly ignoring referendums in which voters rejected new treaties.

The populists have shown a genius for taking worries that contain a nugget of truth—such as that unrestricted immigration is destabilising—and turning them into vote-winning platforms. And they have relentlessly broadened and deepened their appeal as establishment politicians have marginalised the issues that give them life, for example treating worries about migration as nothing but racism. France’s National Front, the most mature of all the populist parties, has already extended its constituency from small businesses to blue-collar workers, pocketing districts that were once dominated by the left and now extending its appeal to public-sector workers.

Some blinkered commentators still see populism as no more than a protest movement: dangerous and disruptive but ultimately doomed by the advance of globalisation and multiculturalism, which are in turn driven by irreversible technological and demographic forces. A glance at history suggests that this view is questionable.

Globalisation went into rapid reverse in the 1920s and 1930s despite the spread of aeroplanes and telephones. The proportion of Americans born abroad was 13.4% in 1920, but after the Immigration Act of 1924 that fell, reaching 4.7% in 1970. The Western elite may be as wrong about the long-term impact of populism as it has been about its short-term prospects.

We are where we are. What happens when populism doesn’t provide the answers that people are looking for? Even worse, what happens if it does?

Labour’s predicament is that Jeremy Corbyn is hugely unpopular. His poll ratings are worse than for any comparable leader in British polling history. The gap between his standing and that of the PrimeMinister Mrs. May is now alarmingly wide. In a recent poll, 17% approved of Corbyn’s leadership and 58% disapproved. The comparable figures for Mrs. May were 46% and 33%. (In both cases, the rest had no opinion).

A recent article in the left-leaning Guardian newspaper suggested that the policies of the Labour Party were actually quite popular with the electorate right up to the point where Corbyn’s name was associated with them.

There are those amongst his many supporters within the party who argue that Corbyn is being judged both prematurely and by the wrong standards. Those attracted to him were looking for a different model of leadership, whose role is to empower, to galvanise and to operate as a standard bearer of a new mass movement.

In this context it could be useful to explore James MacGregor Burns’s distinction between ‘transactional’ and ‘transforming’ leadership. The former envisages leadership in terms of a transaction between the leader and other players in the party. For example, a leader may seek the co-operation and compliance of others through offering a range of incentives, such as policy concessions and personal advancement. Each party to a bargain would be aware of the power resources, proclivities, and preferences of others, and would engage in a process of mutual adjustment.

Transforming leadership, in contrast, envisages as the crucial leadership functions teaching, inspiring and energising, with fervor and dedication in the service of promoting a party’s collective purposes. Endowed with clear visions, transformational leaders are primarily concerned with the advocacy and pursuit of wide-ranging values – such as social justice and equality – and are loath to engage in too many compromises that might jeopardise them.

This approach meshes well as the radical (or ‘hard’) left’s model of the party. Labour’s prime purpose should be to give effect to the ideals and objectives with which it was historically associated. These should be embodied in policies determined by the wider party, and not by any parliamentary conclave. The role of the leader should be to ‘rally their own side effectively’, to appeal to the party’s base and to facilitate both its democratisation and ‘an empowerment of a new grassroots movement.’ Corbyn’s role as a transforming leader is, in short, to invigorate, mobilise and enthuse as the new voice and standard-bearer of a remoralised party.

Corbyn’s ability to perform this role has undoubtedly been severely handicapped by an unrelentingly and often venomously hostile media. It also needs to be said that his limitations as a communicator and his inability to convey the impression of a man possessing the skills and stature of a prime minister in waiting has not helped.

This is widely recognized (at least by his critics). But, even more fundamentally, his very concept of leadership– the leader as transformer – is flawed.

Here it may be useful to take the argument further by citing Weber’s distinction between ‘the ‘ethic of responsibility’ and the ‘ethic of ultimate ends.’ A political leader who accepts the former is animated by a prudential and calculating spirit, is acutely aware of the consequences of any action, and sees political choice in terms of balancing priorities and awkward trade-offs.

But the ‘ethic of responsibility’ can too easily slide into opportunism, careerism, self-serving actions and mere expediency. It is this that the ‘ethic of ultimate ends’ vehemently rejects. It stands for a more steadfast, determined, and uncompromising form of politics driven by principle and honesty. Corbyn’s appeal for many in Labour’s ranks is that he embodied this ‘ethic of ultimate ends’ and rejected Labour’s customary mode of leadership, with all its equivocations, evasions, and half-measures.

The danger is that the personal appropriation of a higher morality and a disregard for pragmatism and compromise can transmute into unyielding and obdurate political stance. As Weber commented, ‘the believer in an ethic of ultimate ends feels “responsible” only for seeing to it that the flame of pure intentions is not quenched.’

This might be compatible with effective leadership when a leader directs a tightly centralised party with full mastery of its key institutions. But Corbyn presides over a party in which power is dispersed among a whole range of institutions, several of which are centres of resistance to his rule. Labour is riven by multiple divisions, over policy, strategy, ideology and, most of all, internal organisation.

Most damagingly, it is suffering from a veritable crisis of legitimacy.

At present, Corbynistas and their critics lack a shared understanding of the ground-rules and values (democracy, accountability, and representation) which should underpin and validate the way in which power is distributed, decisions taken, and sovereignty located. In short, Corbyn both lacks consent and is hemmed in by institutional constraints, without control of decisive levers of power and the confidence of key players.

In such circumstances transforming leadership imbued by an ethic of ultimate ends is peculiarly inappropriate. Labour is a pluralist organisation composed of people attached to a range of often divergent interests, objectives, and values. When this is compounded by profound internal divisions, the skills of a transactional leader are essential.

This mode of leadership ‘requires a shrewd eye for opportunity, a good hand at bargaining, persuading, reciprocating.’ It demands an orientation to leadership governed by the ethic of responsibility, incorporating an open and conciliatory style of engagement, a ‘capacity to modulate personal and political ambitions by patient calculation and realistic appraisal of situations’ and an overriding emphasis upon the importance of reaching consensus and coalition-building. It involves accommodating public opinion with membership preferences, regulating disagreements, astute political maneuvering and a capacity, above all, to hold the party together.

Corbyn has merits – decency, honesty, integrity – but it is not at all evident that concept of leadership is what the party requires.

What happens when nothing changes for the better?

What happens next?

#Statoftheweek We need to build a post #Brexit economy that works for all https://t.co/WcsPQHiB8G pic.twitter.com/0PmazyI1A9

— Joseph Rowntree Fdn. (@jrf_uk) April 4, 2017

Some of the political absurdities that we now have to wade through as part of the brexit discussions or debate.

After he took the role of international trade secretary, Liam Fox boasted that he would have “about a dozen free trade deals outside the EU” ready for when Britain left. But it is of course illegal for Britain, as an EU member state, to negotiate bilateral trade deals. Fox later quietly backtracked on his promise. No one knows what he’s doing with his time at the moment.

In a speech at the Conservative party conference, May promised that Britain would now control how it labels food. But these rules have nothing to do with the EU. They come from a general code at the World Trade Organisation (WTO). For May to deliver on this promise, she would have to adopt the North Korean model of total isolation. She either didn’t know what she was saying was nonsense, or didn’t care.

If you want to sell pharmaceuticals in Europe, they have to have been cleared by European regulators. While we’re in the EU, that’s the case for the UK too. But what happens after we leave? Will a British regulator take up the slack? A fast, hard Brexit of the type being demanded by some Tory MPs would leave a window between leaving the EU and setting up our own regulators. During that period, drug firms wouldn’t be able to get their products authorised for the UK market, so, for a while, there would be no new eczema creams, asthma inhalers or any other new treatments available to British patients.

Directors of trade bodies – many of them facing economic and regulatory disaster – went in to brief David Davis when he was made Brexit secretary. But before they got to his office they were taken to one side by civil servants and advised to go in saying Brexit was full of “opportunities”. Anyone who didn’t tended to be asked to leave after five minutes.

If there’s one thing everyone accepts the Brexit vote demonstrated, it’s that people want to end freedom of movement. Except this isn’t true. Poll after poll taken during and after the campaign found that between 20% and 40% of leave voters either support immigration or prioritise the economy over reducing it – or just want to remain in the single market.

Or at least we didn’t when we voted to leave Europe. Whitehall is now on a massive recruitment drive. We urgently need an army of general trade experts and ones with specialist knowledge in areas such as intellectual property law. The costs are painfully high. Some are quoting day rates of £3,000 to do consultancy work for the UK government. If they are hired full-time, their salaries will be lower – probably around the £100,000 mark.

City bankers don’t have time to sit around waiting to find out what May’s Brexit plan is. In order to avoid losing passporting rights in Europe, they have to register an office with regulators on the continent – a process that could take years. They are therefore likely to make “no regret” decisions, meaning they will do things they wanted to do anyway. In this case, that means moving back-office administrative staff to locations with cheaper rents and lower salaries, such as Warsaw. The less you earn, the more likely you are to be affected.

Brexiters argue that if we don’t get a good deal from the EU, we can fall back on WTO rules. They couldn’t be more wrong. The EU is a member of the Geneva-based WTO too. If the UK tries to unilaterally separate its trade arrangements from the EU without getting its agreement first, Brussels can trigger a trade dispute. For Britain to secure a decent relationship with the WTO, it needs to make sure it is on good terms with the EU.

If Britain does pursue a hard Brexit, things get murky. There are no rules on how an existing WTO member leaves a customs union, because no one has ever been crazy enough to try it. Lawyers at the organisation are trying to sort out how this works and what the process will be.

If Britain is to going to ensure stability during its transition from the EU to independent membership of the WTO, it will have to replicate all the EU’s tariffs (charges on imports and exports). This makes a mockery of everything Brexit stands for, of course, but if we changed any tariff, it would trigger an avalanche of trade disputes and lobbying operations. If Britain was to raise tariffs on ham, for instance, it would trigger protests and formal dispute claims from not just European ham producers, but those all over the world.

There’s an EU agreement at the WTO preventing China from dumping cheap steel in Europe. Without it, plants such as Port Talbot would collapse as Chinese product flooded the market. When Britain leaves the EU, it will claim that it is still a signatory to this agreement and the Chinese will object. This dispute is likely to last for years. If Britain loses, it will likely lose its domestic steel industry.

Ministers want to transfer all EU laws into Britain using the so-called great reform bill. The trouble is, they don’t know where to find them. The Equalities Act, for instance, is a messy mixture of EU and UK legislation. In every area of law, there are bits and pieces of EU directives. Good luck tracking them all down.

Leaving the EU involves three things: an administrative divorce, the untangling of British and EU law, and (probably) a new trade deal. But only the first aspect is dealt with in article 50. The rest is up to Europe’s discretion. If they want to just talk admin, we can’t do much about it.

If European countries don’t like the way article 50 talks go, they could decide to not recognise legal decisions from London. At a snap, British divorcees who live in Europe would suddenly find themselves in a state of marital limbo – with their home country recognising their divorced status, but their adopted country considering them married.

Britain and Ireland enjoy legal protections against EU immigration law which allow them to “continue to make arrangements between themselves relating to the movement of persons between their territories”. This should prevent Brussels imposing a hard border for people in Ireland. But there are no protections against tabloid scare stories. After Brexit, we can expect campaigns about Polish plumbers crossing into England from Ireland to work. It will be nonsense – Polish people could just as easily use tourist visas – but it could be politically effective. If a hard border returns to Ireland, it will be because of Britain, not the EU.

Leaving the single market will sever Britain’s relationship with its largest trading destination, but the problems don’t end there. Europe also has agreements with other major economies such as the US and Japan allowing it to transport goods without expensive and slow border checks. If Britain leaves the single market, we’ll lose these too. Oops.

A bilateral trade deal with the US would see cheaper burgers in the UK. The Americans have lower animal-welfare standards, use growth hormones in their meat and have larger farms. This won’t be good news for British farmers, who will also be facing sky-high export tariffs and a possible end to subsidies. And it won’t be good news for animal rights campaigners. But burger lovers might be pleased.

EU law insists on an independent veterinary presence in abattoirs. The problem is that 95% of the vets doing this job in Britain are European – most of them from Spain. The problem is one of demand. British vets study for years to cure family pets, not watch cows being slaughtered. But Europeans have less of a cultural hang-up about that type of thing and are also willing to accept the lower wages involved. If Britain doesn’t train up more domestic vets for the abattoirs, it won’t be able to sell meat to Europe or properly check it for disease.

British fishermen want the UK to prise open the incredibly complex European system for allocating national quotas of fish stocks and renegotiate the whole thing. That will take a long time and a lot of manpower. If they get it wrong, the UK could face problems. The type of white meat we like for fish and chips doesn’t actually come from the UK – most of it comes from the seas around Norway and Iceland.

The Americans have lower consumer standards than Europe on pretty much everything, from chemical safety to data protection. A bilateral trade deal will see them demand we lower our standards so their products can enter our market more freely. Given how desperate we’ll be, we’re likely to comply.

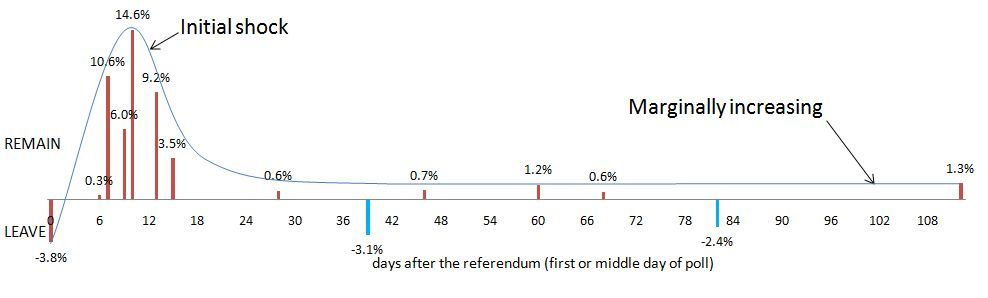

The difference between leave and remain was 3.8% or 1.3 million in favour of Leave. However, in a close analysis, virtually all the polls show that the UK electorate wants to remain in the EU, and has wanted to remain since referendum day. Moreover, according to predicted demographics, the UK will want to remain in the EU for the foreseeable future.

And it makes not a penny of difference because the PM has sent the letter to the EU and we have asked to leave.

There have been more than 13 polls since June 23rd which have asked questions similar to ‘Would you vote the same again’ or ‘Was the country right to vote for Brexit’. People haven’t changed their minds. If you voted leave then you still want to leave. If you voted remain then you still want to remain, but of course many people failed to vote.

Eleven of the polls indicate that the majority in the UK do not want Brexit largely because of those who failed to vote.

It’s important to remember how tight the vote turned out to be. The poll predictions leading up to the referendum narrowed but a significant majority of late polls indicated that the country wanted to remain. The leader of UKIP even conceded defeat on the night of the vote, presumably because the final polls were convincing that Remain would win.

In fact, according to the first post-referendum poll (Ipsos/Newsnight, 29th June), those who did not vote all 12.9m of them, were, by a ratio of 2:1, Remain supporters. It is well known that polls affect both turnout and voting, particularly when it looks as though a particular result is a foregone conclusion. It seems, according to the post-referendum polls, that this was the case. More Remain than Leave supporters who, for whatever reason, found voting too difficult, chose the easier option not to vote, probably because they believed that Remain would win.

Percentage lead of LEAVE or REMAIN according to the polls post June 23rd

Percentage lead of LEAVE or REMAIN according to the polls post June 23rdBy now (March 2017) with Article 50 initiated, there will be approximately 563,000 new 18-year-old voters, with approximately a similar number of deaths, the vast majority (83%) amongst those over 65. Assuming those who voted stick with their decision and based on the age profile of the referendum result, that, alone, year on year adds more to the Remain majority.

A Financial Times model indicated that simply based on that demographic profile, by 2021 the result would be reversed and that will be the case for the foreseeable future.

Sadly nothing less than a second, fairer referendum could redress the unfairness felt by the exclusion from the electorate of both the 16-18s and the non-UK EU residents. This all paints a very sorry picture of the effectiveness of UK democracy. Brexit is not the will of the people in the UK. It never has been. Had all the people spoken on the day the result would almost certainly be what the pollsters had predicted, and what the UK, according to the polls, still wants, and that is to Remain.

We are where are. Calls to unite together behind the brexit banner are loud and insistent.

They can fuck off.