A recent article in the NYTimes asks: “Is America’s Military Big Enough?”

Trump has proposed a $54 billion increase in defense spending, which he said would be “one of the largest increases in national defense spending in American history.”

U.S. defense spending

Source: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Spending (in 2017 dollars) with POTUS changes marked

Past US administrations have increased military spending, but typically to fulfill a specific mission. Jimmy Carter expanded operations in the Persian Gulf. Ronald Reagan pursued an arms race with the Soviet Union, and George W. Bush waged wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

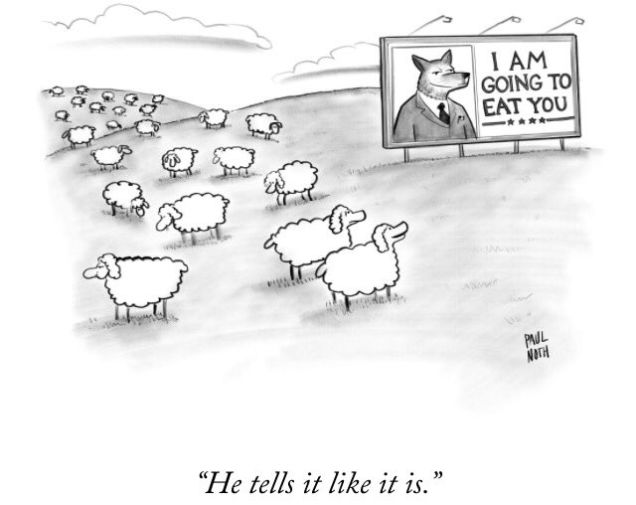

Mr. Trump has not suggested a new mission that would require a military spending increase which kind of begs the question about why. Erin M. Simpson, a national security consultant, called Mr. Trump’s plans “a budget in search of a strategy.”

“Our current strategy is based around us being a superpower in Europe, the Middle East and Asia-Pacific,” said Todd Harrison, the director of defense budget analysis at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “We’ve sized our military to be able to fight more than one conflict at a time in those regions.”

Some of Mr. Trump’s statements have suggested a reduced footprint for the United States military.

He criticized America’s role as a global military stabilizer. Last month, in his first address to a joint session of Congress, he said the United States had “defended the borders of other nations while leaving our own borders wide open. He also called for defusing tensions with Russia, the United States’ chief military competitor. But he has also taken positions that point to a more aggressive military posture. He has advocated challenging China and Iran more directly. He wrote on Twitter that America must “greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability.”

These statements have left analysts unsure about the role Mr. Trump wants the United States military to play in the world.

1 Troops

The United States has approximately 1.3 million active-duty troops, with another 865,000 in reserve, one of the largest fighting forces of any country.

The United States also has a global presence unlike any other nation, with about 200,000 active troops deployed in more than 170 countries. Many are stationed in allied nations in Europe and northeastern Asia. Mr. Trump has criticized these alliances, saying the United States does too much to defend its allies. It seems unlikely, then, that Mr. Trump intends his spending increase to bolster those deployments.

“The general concept of readiness often happens without a conversation about what the forces are for,” said Benjamin H. Friedman, a research fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute in Washington. “They don’t know exactly what they want to do, except that they want a bigger military.”

Mr. Trump wants to increase the number of active-duty military personnel in the Army and Marine Corps by about 70,000 — a rise of about 11% over the current total of 660,000.

The United States increased troop levels in the early 2000s for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, but has scaled down as it has withdrawn from those conflicts. Mr. Trump has been critical of those missions, suggesting that he does not plan to ramp up operations in either conflict.

Gordon Adams, a former senior White House national security budget officer, said, “Unless you decide you’re going to war — and going to war soon — nobody keeps a large military.” Arguably a large military creates it’s own problems. It needs to be paid, fed and watered and kept occupied. Large groups of young fit men need active engagement if they’re not to become a social menace.

2 Air Power

The United States has around 2,200 fighter jets, including about 1,400 operated by the Air Force. Mr. Trump wants to add at least 100 more fighter aircraft to the Air Force.

Analysts informally categorize fighter aircraft by “generations” and there is a broad consensus that American aircraft are more advanced than those of other nations. The military already has plans to spend an estimated $400 billion on new F-35 fighter jets, a fifth-generation plane. But Mr. Trump has not provided any details on which programs he would expand.

Because different warplanes serve different roles at different costs, it is difficult to know what problem Mr. Trump is trying to address by adding 100 fighter aircraft.

3 Naval Power

The United States Navy has 275 surface ships and submarines. Mr. Trump wants to increase that number to 350, including two new aircraft carriers.

The new carriers would add to America’s already overwhelming advantage: More than half of the world’s 18 active aircraft carriers are in the United States Navy.

The world’s 18 active aircraft carriers, by country

In early March, Mr. Trump said that the United States Navy was the smallest it had been since World War I. Most analysts reject this comparison. Technological advances mean that individual ships are far more powerful and versatile than they were a century ago, allowing a single ship to fulfill capabilities that would have once required several ships.

Mr. Trump has not specified new missions that would require additional carriers, which could take years and billions of dollars to build. Expanding the fleet size could come at significant cost. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that building a fleet of around 350 ships could cost about 60 percent more per year than average historical shipbuilding budgets, with a completion date of 2046.

But a larger fleet could help reduce pressure on the Navy, according to Brian Slattery, a policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank. “They’ve had to push those deployments longer and longer because the Navy needs to be in all the same places in the world, and there are fewer ships to do it,” he said.

Others argue that the Navy’s resources are stretched because they have too many deployments and that a more modest strategy around the world would alleviate the strain. “To the extent that they are not in great shape, it’s because they have too many missions,” Mr. Friedman said.

4 Nuclear Weapons

After Mr. Trump tweeted his pledge to expand America’s nuclear capability, he told the talk-show host Mika Brzezinski of MSNBC: “Let it be an arms race. We will outmatch them at every pass and outlast them all.”

He has not specified whether he hopes to build more warheads or develop new weapons systems for delivering them.

The United States and Russia possess the vast majority of the world’s nuclear warheads, although both have reduced their arsenals under a series of treaties. Mr. Trump criticized the latest of those treaties, a 2010 agreement with Moscow called New Start, as “just another bad deal,” according to Reuters.

He has not clarified whether he will consider abrogating the treaty, which could open the way for the United States and Russia to expand their nuclear arsenals and capabilities.

Analysts say Mr. Trump’s call for a nuclear “arms race” could potentially cost billions. But as with other spending plans, he has not articulated a strategic goal.

While Mr. Trump has said that he wants to defeat the Islamic State, he has not explained how increasing the size of the military would accomplish that.

Mr. Trump’s focus on big-ticket items is mainly “useful in more conventional military campaigns,” said Michael C. Horowitz, a University of Pennsylvania professor who studies military leadership. “The kind of investments you would make if you were primarily focused on counterinsurgency campaigns are very different.”

Mr. Trump’s announcements appear to emphasize optics as much as strategy, Mr. Horowitz said. “To the extent that tangible pieces of military equipment symbolize strength, those are things that I think the administration is interested in investing in.” He appears more interested in buying bright and shiny toys for “show and tell”, more money spent to demonstrate size and virility?

One of the worries is that having invested all of this money, potentially buying a lot more kit, the president might feel in need of a war or similar in order to play with these new shiny toys.